(Holocaust at Pearl Harbor – p. 1)

(Holocaust at Pearl Harbor – p. 1)

Month: December 2016

HMS Ulysses, by Alistair MacLean – 1953 [Robert Emil Schulz]

Cap in hand, Ralston sat down opposite the captain.

Cap in hand, Ralston sat down opposite the captain.

Vallery look at him for a long time in silence.

He wondered what to say, how best to say it.

He hated to have to do this.

Richard Vallery also hated war.

He always had hated it,

and he cursed the day it had dragged him out of his comfortable retirement.

At least “dragged” was how he put it;

only Tyndall knew that he had volunteered his services to the Admiralty

on September 1, 1939,

and had had them gladly accepted.

But he hated war.

But he hated war.

Not because it interfered with his lifelong passion for music and literature,

on both of which he was a considerable authority,

not even because it was a perpetual affront to his aestheticism,

to his sense of rightness and fitness.

He hated it because he was a deeply religious man,

because it grieved him to see in mankind the wild beasts of the primeval jungle,

because he thought the cross of his life was already burden enough

without the gratuitous infliction of the mental and physical agony of war,

and, above all,

because he saw war all too clearly as the wild and insensate folly it was, –

as a madness of the mind that settled nothing, proved nothing –

except the old, old truth that God was on the side of the big battalions.

But some things he had to do,

and Vallery had clearly seen that this war was to be his also.

And so he had come back to the service and had grown older

as the bitter years passed, older and frailer,

and more kindly and tolerant and understanding.

Among naval captains – indeed, among men – he was unique.

In his charity, in his humility, Captain Richard Vallery walked alone.

It was a measure of the man’s greatness

that this thought never occurred to him.

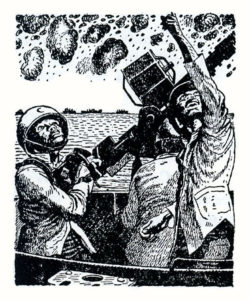

United States Destroyer Operations in World War II, by Theodore Roscoe – 1953 [Lt. Cdr. Fred Freeman] – III

(Winning the Mediterranean – p. 364)

(Winning the Mediterranean – p. 364)  (Central Pacific Push – p. 384)

(Central Pacific Push – p. 384)  (Western Pacific Push – p. 402)

(Western Pacific Push – p. 402)  (Battle off Samar – p. 424)

(Battle off Samar – p. 424)  (U.S.S. Hoel – p. 427)

(U.S.S. Hoel – p. 427)  (U.S.S. Ross – p. 437)

(U.S.S. Ross – p. 437)  (Typhoon – Manila Bay – p. 448)

(Typhoon – Manila Bay – p. 448)  (Typhoon – Manila Bay – p. 459)

(Typhoon – Manila Bay – p. 459)  (Okinawa Invasion – p. 485)

(Okinawa Invasion – p. 485)  (Small Boys Finish Big Job – p. 501)

(Small Boys Finish Big Job – p. 501)

United States Destroyer Operations in World War II, by Theodore Roscoe – 1953 [Lt. Cdr. Fred Freeman] – II

United States Submarine Operations in World War II, by Theodore Roscoe – 1949 [Lt. Cdr. Fred Freeman] – I

United States Destroyer Operations in World War II, by Theodore Roscoe – 1953 [Lt. Cdr. Fred Freeman] – I

Winesburg, Ohio, by Sherwood Anderson – 1946 [Robert Jonas]

It will perhaps be somewhat difficult for the men and women of a later day

to understand Jesse Bentley.

In the Last fifty years a vast change has taken place in the lives of our people.

A revolution has in fact taken place.

The coming of industrialism, attended by all the roar and rattle of affairs,

the shrill cries of millions of new voices that have come among us from over seas,

the going and coming of trains,

the growth of cities,

the building of the interurban car lines

that weave in and out of towns and past farmhouses,

and now in these later days the coming of the automobiles

has worked a tremendous change in the lives and the habits

of thought of our people of Mid-America.

Books,

badly imagined and written though they may be in the hurry of our times,

are in every household,

magazines circulate by the millions of copies,

newspapers are everywhere.

In our day a farmer standing by a stove in the store in his village

has his mind filled to overflowing with the words of other men.

The newspapers and the magazines have pumped him full.

Much of the old brutal ignorance that had in it also

a kind of beautiful childlike innocence is gone forever.

The farmer by the stove is brother to the men of the cities,

and if you listen you will find him talking as glibly and senselessly

as the best city man of us all.

Christ Stopped at Eboli, by Carlo Levi – 1948 [Robert Jonas]

The truth is that the internecine war among the gentry is the same in every village of Lucania.

The truth is that the internecine war among the gentry is the same in every village of Lucania.

The upper classes have not the means to live with decorum and self-respect.

The young men of promise, and even those barely able to make their way, leave the village.

The most adventurous go off to America, as the peasants do, and the others to Naples or Rome; none return.

Those who are left in the villages are the discarded, who have no talents, the physically deformed, the inept and the lazy; greed and boredom combine to dispose them to evil.

Small parcels of farm land do not assure them a living and, in order to survive, these misfits must dominate the peasants and secure for themselves the well-paid posts of druggist, priest, marshal of the carabinieri, and so on.

It is, therefore, a matter of life and death to have the rule in their own hands, to hoist themselves on their relatives and friends into top jobs.

This is the root of the endless struggle to obtain power and to keep it from others, a struggle with the narrowness of their surroundings, enforced idleness, and a mixture of personal and political motives render continuous and savage.

Every day anonymous letters from every village of Lucania arrived at the prefecture.

And at the prefecture they were, apparently, far from dissatisfied with this state of affairs, even if they said the contrary.

__________

All that people say about the people of the South, things I once believed myself: the savage rigidity or their morals, their Oriental jealousy, the fierce sense of honor leading to crimes of passion and revenge, all these are but myths.

Perhaps they existed a long time ago and something of them is left in the way of a stiff conventionality.

But emigration has changed the picture.

The men have gone and the women have taken over.

Many a woman’s husband is in America.

For a year, or even two, he writes to her, then he drops out of her ken, perhaps he forms other family ties; in any case he disappears and never comes back.

The wife waits for him a year, or even two; then some opportunity arises and a baby is the result.

A great part of the children are illegitimate, and the mother holds absolute sway. Gagliano has twelve hundred inhabitants, and there are two thousand men from Gagliano in America.

Grassano had five thousand inhabitants and almost the same number have emigrated.

In the villages the women outnumber the men and the father’s identity is no longer so strictly important; honor is dissociated from paternity, because a matriarchal regime prevails.

One, Two, Three, Infinity, by George Gamow – 1957 [Robert Jonas]

According to the best available information concerning the galactic masses, it seems that at present the kinetic energy of receding galaxies is several times greater than their mutual potential gravitational energy, from which it would follow that our universe is expanding into infinity without any chance of ever being pulled more closely together again by the forces of gravity.

According to the best available information concerning the galactic masses, it seems that at present the kinetic energy of receding galaxies is several times greater than their mutual potential gravitational energy, from which it would follow that our universe is expanding into infinity without any chance of ever being pulled more closely together again by the forces of gravity.

It must be remembered, however, that most of the numerical data pertaining to the universe as a whole are not very exact, and it is possible that future studies will reverse this conclusion.

But even if the expanding universe does stop suddenly in its tracks, and turn back in a movement of compression, it will be billions of years before that terrible day envisioned by the Negro spiritual, “when the stars begin to fall,” and we are crushed under the weight of collapsing galaxies!

What was this high explosive material that sent the fragments of the universe flying apart at such a terrific speed?

The answer may be somewhat disappointing: there probably was no explosion in the ordinary sense of the word.

The universe is now expanding because in some previous period of its history (which, of course, no record has been left), it contracted from infinity into a very dense state and then rebounded, as it were, propelled by the strong elastic forces inherent in compressed matter.

If you were to enter a game room just in time to see a ping-pong ball rising from the floor high into the air, you would conclude (without really thinking about it) that in the instant before you entered the room the ball had fallen to the floor from a comparable height, and was jumping up again because of its elasticity.

We can now send our imagination flying beyond any limits, and ask ourselves whether during the precompressive stages of the universe everything that is now happening was happening in reverse order.

Were you reading this book from the last page to the first some six or eight billion years ago?

And did the people of that time produce fried chickens from their mouths, put life into them in the kitchen, and send them to the farm where they grew from adulthood to babyhood, finally crawled into eggshells, and after some weeks became fresh eggs?

Interesting as they are, such questions cannot be answered from the purely scientific point of view, since the maximum compression of the universe, which squeezed all matter into a uniform nuclear fluid, must have completely obliterated all the records of the earlier compressive stages.