|

By Henri Astier

BBC News, Clichy-sous-Bois, France

|

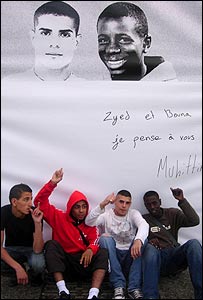

Clichy youths have not forgotten Zyed and Bouna

|

In Clichy-sous-Bois, a drab suburb north-east of Paris, the memory of two local teenagers who died a year ago is very much alive.

The boys' portraits are posted throughout the city's dilapidated housing estates, with the caption: "Zyed and Bouna, I'm thinking of you."

As Clichy marks the anniversary of their death - which sparked three weeks of rioting across France's largely immigrant suburbs - anger is still seething among youths.

"Nothing has changed," says Benj, 16. "We still don't know why Zyed and Bouna died. We want to know the truth."

Zyed Benna, 17, and Bouna Traore, 15, were electrocuted while hiding in a transformer on 27 October 2005.

Many residents are convinced they were being chased by police - which the authorities deny.

Promises

For Clichy's youths, the incident was part of a pattern of provocation by police and neglect by the authorities that still prevails.

"The cops were responsible for the riots," says Benj. "They only come here to give us a hard time. We live in the same filthy environment. We want facilities - there are not even play areas for kids here."

Another 16-year-old agrees: "Police treat us like delinquents. And the situation has deteriorated in the past year."

This bleak assessment is confirmed by Clichy's youth workers.

"Kids do not burn cars just for fun," educator Mamadou Kanoute says.

"The violence expressed deep-rooted problems: unemployment, job insecurity, discrimination, a feeling of being marginalised. And things are going from bad to worse."

Frustration is greater, he adds, since the government has not kept promises - made after the unrest - of more funding for jobs and facilities in the suburbs.

Olivier Klein, Clichy's deputy mayor, also feels the government's response has been inadequate.

No-one, he concedes, expected the city's long-standing problems - run-down housing, poor transport links, bad schools, rampant crime and unemployment reaching 40% in places - to be resolved in a year.

|

2005 UNREST IN FIGURES

9193 cars burnt

2,921 arrests

21 nights of riots

Source: French police

|

But Mr Klein was at least hoping for a concerted effort to start addressing these challenges. This, he says, has not happened.

"We got no extra subsidies," he says. "The only commitment we got from the government after the riots was a decision to build a police station."

Mr Klein approves of the move, as Clichy does not have a police station.

But by itself, he contends, this will do little to improve life in what he admits is a "ghetto".

Restless

The government is fully aware that tensions are high in the suburbs. Earlier this month, a leaked intelligence report warned that unrest could erupt again at any time - especially in the Paris area.

It noted that any coming violence could be less spontaneous but "more structured" and target police.

|

Youths from the French suburbs say they think all the ingredients for chaos remain

|

There has indeed been an increase in incidents in recent weeks - including an attack on police in Epinay-sur-Seine, north of the capital, and the burning of buses in Grigny to the south, Nanterre in the north-west and Bagnolet to the east.

Anger is particularly rife among those aged 14-20, and their elders find it increasingly difficult to control them.

"My younger brother wanted to join the riots last year but I managed to stop him," says Hadri, 29 - a member of AC Lefeu, a group formed in Clichy after the unrest to highlight the suburbs' problems.

However Hadri may struggle to contain his brother in the future: "I felt hypocritical telling him not to go - I understood his sense of injustice. I too felt like rioting."

Hadri may feel ambivalent about the disturbances, but he is thankful that they drew attention to France's neglected suburbs.

"If it had not been for the revolt you journalists wouldn't be here," he says.

Powder keg

It would be wrong, however, to regard the rioters as representative of the suburbs' population at large. Most adult residents were appalled to see their cars torched and their estates go up in flames.

Laurence Ribeaucourt, a social worker in Montfermeil near Clichy, said no one wants a repeat. She is haunted by an incident she witnessed while dining with a local family at the height of the unrest.

Buses and cars are still being set alight by suburb youths

|

"Fighting erupted outside - I was very afraid. There were two young boys at the table and they were determined to take part.

"Their mother tried to block the door, but they were too strong and in the end she had to stand aside. As they left she was devastated and racked with guilt."

Ms Ribeaucourt says the mother was not alone - many parents blamed themselves for the riots.

"They felt they had not given their children a decent future and had a deep sense of failure."

Omar Dawson, 27, who works with youths in Grigny, is also among those who think the suburbs could have done without the publicity generated by the violence.

"Riots make good pictures and capture attention, but in the end they have brought little. Those who have benefited are politicians promising to crack down on crime."

However rioters rarely think in terms of cost and benefits - they act on impulse, often taking their cue from each other.

And the conditions that led unrest to spread like wildfire are still in place a year on.

~RS~q~RS~~RS~z~RS~04~RS~)