| |

| Version | 3.0 |

| Editors | Mark Davis (Google Inc.), Peter Edberg (Apple Inc.) |

| Date | 2016-06-03 |

| This Version | http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr51/tr51-7.html |

| Previous Version | http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr51/tr51-5.html |

| Latest Version | http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr51/ |

| Latest Proposed Update | http://www.unicode.org/reports/tr51/proposed.html |

| Revision | 7 |

This document provides design guidelines for improving the interoperability of emoji characters across platforms and implementations. It also provides data that designates which characters are considered to be emoji, which emoji should be displayed by default with a text style versus an emoji style, and which can be displayed with a variety of skin tones.

This document has been reviewed by Unicode members and other interested parties, and has been approved for publication by the Unicode Consortium. This is a stable document and may be used as reference material or cited as a normative reference by other specifications.

A Unicode Technical Report (UTR) contains informative material. Conformance to the Unicode Standard does not imply conformance to any UTR. Other specifications, however, are free to make normative references to a UTR.

Please submit corrigenda and other comments with the online reporting form [Feedback]. Related information that is useful in understanding this document is found in the References. For the latest version of the Unicode Standard, see [Unicode]. For a list of current Unicode Technical Reports, see [Reports]. For more information about versions of the Unicode Standard, see [Versions].

Emoji are pictographs (pictorial symbols) that are typically presented in a colorful cartoon form and used inline in text. They represent things such as faces, weather, vehicles and buildings, food and drink, animals and plants, or icons that represent emotions, feelings, or activities.

Emoji on smartphones and in chat and email applications have become extremely popular worldwide. As of 2015, for example, Instagram reported that “in March of this year, nearly half of text [on Instagram] contained emoji.” Individual emoji also vary greatly in popularity (and even by country), as described in the SwiftKey Emoji Report. See emoji press page for details about these reports and others.

Emoji are most often used in social media—in quick, short messages where they connect with the reader and add flavor, color, and emotion. Emoji do not have the grammar or vocabulary to substitute for written language. In social media, emoji make up for the lack of gestures, facial expressions, and intonation that are found in speech. They also add useful ambiguity to messages, allowing the writer to convey many different possible concepts at the same time. Many people are also attracted by the challenge of composing messages in emoji, and puzzling out emoji messages.

The word emoji comes from the Japanese:

絵 (e ≅ picture) 文 (mo ≅ writing) 字 (ji ≅ character).

Emoji may be represented internally as graphics or they may be represented by normal glyphs encoded in fonts like other characters. These latter are called emoji characters for clarity. Some Unicode characters are normally displayed as emoji; some are normally displayed as ordinary text, and some can be displayed both ways.

There’s been considerable media attention to emoji since they appeared in the Unicode Standard, with increased attention starting in late 2013. For example, there were some 6,000 articles on the emoji appearing in Unicode 7.0, according to Google News. See the emoji press page for many samples of such articles, and also the Keynote from the 38th Internationalization & Unicode Conference.

Emoji became available in 1999 on Japanese mobile phones. There was an early proposal in 2000 to encode DoCoMo emoji in Unicode. At that time, it was unclear whether these characters would come into widespread use—and there was not support from the Japanese mobile phone carriers to add them to Unicode—so no action was taken.

The emoji turned out to be quite popular in Japan, but each mobile phone carrier developed different (but partially overlapping) sets, and each mobile phone vendor used their own text encoding extensions, which were incompatible with one another. The vendors developed cross-mapping tables to allow limited interchange of emoji characters with phones from other vendors, including email. Characters from other platforms that could not be displayed were represented with 〓 (U+3013 GETA MARK), but it was all too easy for the characters to get corrupted or dropped.

When non-Japanese email and mobile phone vendors started to support

email exchange with the Japanese carriers, they ran into those

problems. Moreover, there was no way to represent these characters in

Unicode, which was the basis for text in all modern programs. In

2006, Google started work on converting Japanese emoji to Unicode

private-use codes, leading to the development of internal mapping

tables for supporting the carrier emoji via Unicode characters in 2007 .

.

There are, however, many problems with a private-use approach, and thus a proposal was made to the Unicode Consortium to expand the scope of symbols to encompass emoji. This proposal was approved in May 2007, leading to the formation of a symbols subcommittee, and in August 2007 the technical committee agreed to support the encoding of emoji in Unicode based on a set of principles developed by the subcommittee. The following are a few of the documents tracking the progression of Unicode emoji characters.

| Date | Doc No. | Title | Authors |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2000-04-26 | L2/00-152 | NTT DoCoMo Pictographs | Graham Asher (Symbian) |

| 2006-11-01 | L2/06-369 | Symbols (scope extension) | Mark Davis (Google) |

| 2007-08-03 | L2/07-257 | Working Draft Proposal for Encoding Emoji Symbols | Kat Momoi, Mark Davis, Markus Scherer (Google) |

| 2007-08-09 | L2/07-274R | Symbols draft resolution | Mark Davis (Google) |

| 2007-09-18 | L2/07-391 | Japanese TV Symbols (ARIB) | Michel Suignard (Microsoft) |

| 2009-01-30 | L2/09-026 | Emoji Symbols Proposed for New Encoding | Markus Scherer, Mark Davis, Kat Momoi, Darick

Tong (Google); Yasuo Kida, Peter Edberg (Apple) |

| 2009-03-05 | L2/09-025R2 | Proposal for Encoding Emoji Symbols | |

| 2010-04-27 | L2/10-132 | Emoji Symbols: Background Data | |

| 2011-02-15 | L2/11-052R | Wingdings and Webdings Symbols | Michel Suignard |

To find the documents in this table, see UTC Documents.

In 2009, the first Unicode characters explicitly intended as emoji were added to Unicode 5.2 for interoperability with the ARIB (Association of Radio Industries and Businesses) set. A set of 722 characters was defined as the union of emoji characters used by Japanese mobile phone carriers: 114 of these characters were already in Unicode 5.2. In 2010, the remaining 608 emoji characters were added to Unicode 6.0, along with some other emoji characters. In 2012, a few more emoji were added to Unicode 6.1, and in 2014 a larger number were added to Unicode 7.0. Additional characters have been added since then, based on the Selection Factors found in Submitting Emoji Character Proposals.

Here is a summary of when some of the major sources of pictographs used as emoji were encoded in Unicode. These sources include other characters in addition to emoji.

| Source | Abbr |

L |

Dev. Starts |

Released |

Unicode Version |

Sample Character |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

B&W |

Color

|

Code |

Name | ||||||

| Zapf Dingbats | ZDings |

z |

1989 |

1991-10 |

U+270F |

pencil | |||

| ARIB | ARIB |

a |

2007 |

2008-10-01 |

U+2614 |

umbrella with rain drops | |||

| Japanese carriers | JCarrier |

j |

2007 |

2010-10-11 |

U+1F60E |

smiling face with sunglasses | |||

| Wingdings & Webdings | WDings |

w |

2010 |

2014-06-16 |

U+1F336 |

hot pepper | |||

Unicode characters can correspond to multiple sources. The L column contains single-letter abbreviations for use in charts [emoji-charts] and data files [emoji-data]. Characters that do not correspond to any of these sources can be marked with Other (x).

For a detailed view of when various source sets of emoji were added to Unicode, see emoji-versions-sources [emoji-charts]. The data file [JSources] shows the correspondence to the original Japanese carrier symbols.

The Selected Products table lists when Unicode emoji characters were incorporated into selected products. (The Private Use characters — PUA — were a temporary solution.)

| Date | Product | Version | Emoji Support | Display | Input | Notes, Links |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008-01 | GMail mobile | PUA | color | palette | モバイル

Gmail が携帯絵文字に対応しました |

|

| 2008-10 | GMail web | PUA | color | palette | Gmail

で絵文字が使えるようになりました |

|

| 2008-11 | iPhone | iPhone OS 2.2 | PUA | color | palette | Softbank users, others via 3rd party apps. CNET Japan

article on Nov. 21, 2008. on Nov. 21, 2008.

|

| 2011-07 | Mac | OSX 10.7 | Unicode 6.0 | color | Character Viewer | |

| 2011-11 | iPhone, iPad | iOS 5 | Unicode 6.0 | color | +emoji keyboard | |

| 2012-06 | Android | Jelly Bean | B&W | 3rd party input | …Quick

List of Jelly Bean Emoji… |

|

| 2012-09 | iPhone, iPad | iOS 6 | + variation selectors | |||

| 2012-08 | Windows | 8 | Unicode only; no emoji variation sequences | desktop/tablet: b&w; phone: color |

integrated in touch keyboards | |

| 2013-08 | Windows | 8.1 | Unicode only; emoji variation sequences | all: color | touch keyboards; phone: text prediction features (e.g. “love” -> ❤) | Color using scalable glyphs (OpenType extension) |

| 2013-11 | Android | Kitkat | color | native keyboard | …new,

colorful Emoji in Android KitKat |

|

| 2015-04 | iPhone, iPad, Mac | iOS 8.3, OSX 10.10.3 | + emoji modifiers, ZWJ sequences for people groupings | color | emoji keyboard with long press for modifier sequences, separate keys for ZWJ sequences | |

| 2015-12 | Android | Marshmallow 6.0.1 | + ZWJ sequences for people groupings | color | separate keys for ZWJ sequences |

People often ask how many emoji are in the Unicode Standard. This question does not have a simple answer, because there is no clear line separating which pictographic characters should be displayed with a typical emoji style. For a complete picture, see Which Characters are Emoji.

The colored images used in this document and associated charts [emoji-charts] are for illustration only. They do not appear in the Unicode Standard, which has only black and white images. They are either made available by the respective vendors for use in this document, or are believed to be available for non-commercial reuse. Inquiries for permission to use vendor images should be directed to those vendors, not to the Unicode Consortium. For more information, see Rights to Emoji Images.

The term emoticon refers to a series of text characters (typically punctuation or symbols) that is meant to represent a facial expression or gesture (sometimes when viewed sideways), such as the following.

;-)

Emoticons predate Unicode and

emoji ,

but were later adapted to include Unicode characters. The

following examples use not only ASCII characters, but also U+203F ( ‿

), U+FE35 ( ︵ ), U+25C9 ( ◉ ), and U+0CA0 ( ಠ ).

,

but were later adapted to include Unicode characters. The

following examples use not only ASCII characters, but also U+203F ( ‿

), U+FE35 ( ︵ ), U+25C9 ( ◉ ), and U+0CA0 ( ಠ ).

^‿^

◉︵◉

ಠ_ಠ

Often implementations allow emoticons to be used to input emoji. For

example, the emoticon ;-) can be mapped to ![]() in a

chat window. The term emoticon is sometimes used in a

broader sense, to also include the emoji for facial expressions and

gestures. That broad sense is used in the Unicode block name Emoticons,

covering the code points from U+1F600 to U+1F64F.

in a

chat window. The term emoticon is sometimes used in a

broader sense, to also include the emoji for facial expressions and

gestures. That broad sense is used in the Unicode block name Emoticons,

covering the code points from U+1F600 to U+1F64F.

Unicode is the foundation for text in all modern software: it’s how

all mobile phones, desktops, and other computers represent the text

of every language. People are using Unicode every time they type a

key on their phone or desktop computer, and every time they look at a

web page or text in an application. It is very important that the

standard be stable, and that every character that goes into it be

scrutinized carefully. This requires a formal process with a long

development cycle. For example, the ![]() dark

sunglasses character was first proposed years before it was released

in Unicode 7.0.

dark

sunglasses character was first proposed years before it was released

in Unicode 7.0.

Characters considered for encoding must normally be in widespread use

as elements of text. The emoji and various symbols were added to

Unicode because of their use as characters for text-messaging in a

number of Japanese manufacturers’ corporate standards, and other

places, or in long-standing use in widely distributed fonts such as

Wingdings and Webdings. In many cases, the characters were added for

complete round-tripping to and from a source set, not

because they were inherently of more importance than other

characters. For example, the ![]() clamshell

phone character was included because it was in Wingdings and

Webdings, not because it is more important than, say, a “skunk”

character.

clamshell

phone character was included because it was in Wingdings and

Webdings, not because it is more important than, say, a “skunk”

character.

In some cases, a character was added to complete a set: for example,

a ![]() rugby football

character was added to Unicode 6.0 to complement the

rugby football

character was added to Unicode 6.0 to complement the ![]() american

football character (the

american

football character (the ![]() soccer ball had

been added back in Unicode 5.2). Similarly, a mechanism was added

that could be used to represent all country flags (those

corresponding to a two-letter unicode_region_subtag),

such as the flag for Canada,

even though the Japanese carrier set only had 10 country flags.

soccer ball had

been added back in Unicode 5.2). Similarly, a mechanism was added

that could be used to represent all country flags (those

corresponding to a two-letter unicode_region_subtag),

such as the flag for Canada,

even though the Japanese carrier set only had 10 country flags.

The data does not include non-pictographs, except for those in Unicode that are used to represent characters from emoji sources, for compatibility, such as:

![]() or

or ![]()

Game pieces, such as the dominos (🀰 🀱 🀲 ... 🂑 🂒), are currently

not included as emoji, with the exceptions of U+1F0CF ( ![]() ) PLAYING CARD BLACK JOKER and U+1F004 (

) PLAYING CARD BLACK JOKER and U+1F004 ( ![]() )

MAHJONG TILE RED DRAGON. These are included because they correspond

each to an emoji character from one of the carrier sets.

)

MAHJONG TILE RED DRAGON. These are included because they correspond

each to an emoji character from one of the carrier sets.

The selection factors used to weigh the encoding of prospective candidates are found in Selection Factors in Submitting Emoji Character Proposals. That document also provides instructions for submitting proposals for new emoji.

For a list of frequently asked questions on emoji, see the Unicode Emoji FAQ.

This document provides:

It also provides background information about emoji, and discusses longer-term approaches to emoji.

As new Unicode characters are added or the “common practice” for emoji usage changes, the data and recommendations supplied by this document may change in accordance. Thus the recommendations and data will change across versions of this document.

The following provide more formal definitions of some of the terms used in this document. Readers who are more interested in other features of the document may choose to continue from Section 2 Design Guidelines .

ED-1. emoji — A colorful pictograph that can be used inline in text. Internally the representation is either (a) an image or (b) an encoded character. The term emoji character can be used for (b) where not clear from context.

ED-2. emoticon — (1) A series of text characters (typically punctuation or symbols) that is meant to represent a facial expression or gesture such as ;-) (2) a broader sense, also including emoji for facial expressions and gestures.

ED-3. emoji character — A character that is recommended for use as emoji.

- These are the characters with the Emoji property. See Annex A: Emoji Properties and Data Files.

ED-4. (This definition has been removed.)

ED-5. (This definition has been removed.)

For more information, see Section 3 Which Characters are Emoji.

ED-6. default emoji presentation character — A character that, by default, should appear with an emoji presentation, rather than a text presentation.

- These are the characters with the Emoji_Presentation property. See Annex A: Emoji Properties and Data Files.

ED-7. default text presentation character — A character that, by default, should appear with a text presentation, rather than an emoji presentation.

- These are the characters that do not have the Emoji_Presentation property. That is, their Emoji_Presentation property value is No. See Annex A: Emoji Properties and Data Files.

For more details about emoji and text presentation, see Section 2 Design Guidelines and Section 4 Presentation Style .

ED-8. emoji variation selector — Either of the two variation selectors used to request a text or emoji presentation for an emoji character:

- U+FE0E VARIATION SELECTOR-15 (VS15) for a text presentation

- U+FE0F VARIATION SELECTOR-16 (VS16) for an emoji presentation

ED-9. emoji variation sequence — A variation sequence listed in [VSData] that contains an emoji variation selector.

ED-10. (This definition has been removed.)

ED-11. emoji modifier — A character that can be used to modify the appearance of a preceding emoji in an emoji modifier sequence.

- These are the characters with the Emoji_Modifier property. See Annex A: Emoji Properties and Data Files.

ED-12. emoji modifier base — A character whose appearance can be modified by a subsequent emoji modifier in an emoji modifier sequence.

- These are the characters with the Emoji_Modifier_Base property. See Annex A: Emoji Properties and Data Files.

- They are also listed in Characters Subject to Emoji Modifiers.

ED-13. emoji modifier sequence — A sequence of the following form:

emoji_modifier_sequence :=

emoji_modifier_base emoji_modifier

For more details about emoji modifiers, see Section 2.2 Diversity.

ED-14. emoji flag sequence — A sequence of two Regional Indicator characters, where the corresponding ASCII characters are valid region sequences as specified by Unicode region subtags in [CLDR], with idStatus="regular" or "deprecated". See also Annex B: Flags.

emoji_flag_sequence :=

regional_indicator regional_indicatorED-14a. emoji combining sequence — A sequence of the following form:

emoji_combining_sequence :=

emoji_character non_spacing_mark*

| emoji_variation_sequence non_spacing_mark*ED-15. emoji core sequence — A sequence of the following form:

emoji_core_sequence :=

emoji_combining_sequence

| emoji_modifier_sequence

| emoji_flag_sequenceED-15a. emoji zwj element — A more limited element that can be used in a ZWJ sequence, as follows:

emoji_zwj_element :=

emoji_character

| emoji_variation_sequence

| emoji_modifier_sequenceED-16. emoji zwj sequence — An emoji sequence with at least one joiner character.

emoji_zwj_sequence :=

emoji_zwj_element ( ZWJ emoji_zwj_element )+ED-17. emoji sequence — A core sequence or ZWJ sequence, as follows:

emoji_sequence :=

emoji_core_sequence

| emoji_zwj_sequence

For recommendations on the use of variation selectors in emoji sequences, see Section 2.4 Emoji Implementation Notes.

Unicode characters can have many different presentations as text. An "a" for example, can look quite different depending on the font. Emoji characters can have two main kinds of presentation:

More precisely, a text presentation is a simple foreground shape whose color which is determined by other information, such as setting a color on the text, while an emoji presentation determines the color(s) of the character, and is typically multicolored. In other words, when someone changes the text color in a word processor, a character with an emoji presentation will not change color.

Any Unicode character can be presented with a text presentation, as in the Unicode charts. For the emoji presentation, both the name and the representative glyph in the Unicode chart should be taken into account when designing the appearance of the emoji, along with the images used by other vendors. The shape of the character can vary significantly. For example, here are just some of the possible images for U+1F36D LOLLIPOP, U+1F36E CUSTARD, U+1F36F HONEY POT, and U+1F370 SHORTCAKE:

While the shape of the character can vary significantly, designers

should maintain the same “core” shape, based on the shapes used

mostly commonly in industry practice. For example, a U+1F36F HONEY

POT encodes for a pictorial representation of a pot of honey, not for

some semantic like "sweet". It would be unexpected to

represent U+1F36F HONEY POT as a sugar cube, for example. Deviating

too far from that core shape can cause interoperability problems: see

accidentally-sending-friends-a-hairy-heart-emoji .

Direction (whether a person or object faces to the right or left, up

or down) should also be maintained where possible, because a change

in direction can change the meaning: when sending

.

Direction (whether a person or object faces to the right or left, up

or down) should also be maintained where possible, because a change

in direction can change the meaning: when sending ![]()

![]()

![]() “crocodile shot by

police”, people expect any recipient to see the pistol pointing in

the same direction as when they composed it. Similarly, the U+1F6B6 pedestrian

should face to the left

“crocodile shot by

police”, people expect any recipient to see the pistol pointing in

the same direction as when they composed it. Similarly, the U+1F6B6 pedestrian

should face to the left ![]() , not to the right.

, not to the right.

General-purpose emoji for people and body parts should also not be

given overly specific images: the general recommendation is to be as

neutral as possible regarding race, ethnicity, and gender. Thus for

the character U+1F777 CONSTRUCTION WORKER, the

recommendation is to use a neutral graphic like

![]() (with an orange skin tone)

instead of an overly specific image like

(with an orange skin tone)

instead of an overly specific image like

![]() (with a light skin tone). This includes the

emoji modifier base characters

listed in

Sample Emoji Modifier Bases.

The emoji modifiers allow for variations in skin tone to

be expressed.

(with a light skin tone). This includes the

emoji modifier base characters

listed in

Sample Emoji Modifier Bases.

The emoji modifiers allow for variations in skin tone to

be expressed.

Unicode 9.0 adds several characters intended to complete gender pairs, and there are ongoing efforts to provide more gender choices in the future. For more information, see the Unicode Emoji FAQ.

Names of symbols such as BLACK MEDIUM SQUARE or WHITE MEDIUM SQUARE are not meant to indicate that the corresponding character must be presented in black or white, respectively; rather, the use of “black” and “white” in the names is generally just to contrast filled versus outline shapes, or a darker color fill versus a lighter color fill. Similarly, in other symbols such as the hands U+261A BLACK LEFT POINTING INDEX and U+261C WHITE LEFT POINTING INDEX, the words “white” and “black” also refer to outlined versus filled, and do not indicate skin color.

However, other color words in the name, such as YELLOW, typically provide a recommendation as to the emoji presentation, which should be followed to avoid interoperability problems.

Emoji characters may not always be displayed on a white background. They are often best given a faint, narrow contrasting border to keep the character visually distinct from a similarly colored background. Thus a Japanese flag would have a border so that it would be visible on a white background, and a Swiss flag have a border so that it is visible on a red background.

Current practice is for emoji to have a square aspect ratio, deriving from their origin in Japanese. For interoperability, it is recommended that this practice be continued with current and future emoji.

Flag emoji characters are discussed in Annex B: Flags.

Combining marks may be applied to emoji, just like they can be

applied to other characters. When that is done, the combination

should take on an emoji presentation. For example, a ![]() is represented as the sequence "1" plus an emoji variation

selector plus U+20E3 COMBINING ENCLOSING KEYCAP. Systems are

unlikely, however, to support arbitrary combining marks with

arbitrary emoji. Aside from U+20E3, the most likely to be supported

is:

is represented as the sequence "1" plus an emoji variation

selector plus U+20E3 COMBINING ENCLOSING KEYCAP. Systems are

unlikely, however, to support arbitrary combining marks with

arbitrary emoji. Aside from U+20E3, the most likely to be supported

is:

For example:

No combining marks other than U+20E0 and U+20E3, however, are recommended for usage.

The following emoji have explicit gender, based on the name and explicit, intentional contrasts with other characters.

U+1F466 boy

U+1F467 girl

U+1F468 man

U+1F469 woman

U+1F474 older man

U+1F475 older woman

U+1F46B man and woman holding hands

U+1F46C two men holding

hands

U+1F46D two women holding hands

U+1F6B9 mens

symbol

U+1F6BA womens symbol

U+1F478 princess

U+1F46F woman with bunny ears

U+1F470 bride with veil

U+1F472 man with gua pi mao

U+1F473 man with turban

U+1F574 man in business suit

levitating

U+1F385 father christmas

All others should be depicted in a gender-neutral way.

People all over the world want to have emoji that reflect more human diversity, especially for skin tone. The Unicode emoji characters for people and body parts are meant to be generic, yet following the precedents set by the original Japanese carrier images, they are often shown with a light skin tone instead of a more generic (nonhuman) appearance, such as a yellow/orange color or a silhouette.

Five symbol modifier characters that provide for a range of skin

tones for human emoji were released in Unicode Version 8.0

(mid-2015). These characters are based on the six tones of the

Fitzpatrick scale, a recognized standard for dermatology (there are

many examples of this scale online, such as FitzpatrickSkinType.pdf ).

The exact shades may vary between implementations.

).

The exact shades may vary between implementations.

| Code | Name | Samples | |

|---|---|---|---|

| U+1F3FB | EMOJI MODIFIER FITZPATRICK TYPE-1-2 | ||

| U+1F3FC | EMOJI MODIFIER FITZPATRICK TYPE-3 | ||

| U+1F3FD | EMOJI MODIFIER FITZPATRICK TYPE-4 | ||

| U+1F3FE | EMOJI MODIFIER FITZPATRICK TYPE-5 | ||

| U+1F3FF | EMOJI MODIFIER FITZPATRICK TYPE-6 | ||

These characters have been designed so that even where diverse color images for human emoji are not available, readers can see what the intended meaning was.

The default representation of these modifier characters when used alone is as a color swatch. Whenever one of these characters immediately follows certain characters (such as WOMAN), then a font should show the sequence as a single glyph corresponding to the image for the person(s) or body part with the specified skin tone, such as the following:

![]() +

+ ![]() →

→ ![]()

However, even if the font doesn’t show the combined character, the user can still see that a skin tone was intended:

![]()

![]()

This may fall back to a black and white stippled or hatched image such as when colorful emoji are not supported.

![]() +

+ ![]() →

→ ![]()

When a human emoji is not immediately followed by a emoji modifier character, it should use a generic, non-realistic skin tone, such as:

RGB #FFCC22 (one of the

colors typically used for the smiley faces)RGB #3399CCRGB #CCCCCCFor example, the following set uses gray as the generic skin tone:

![]()

As to hair color, dark hair tends to be more neutral, because people of every skin tone can have black (or very dark brown) hair—however, there is no requirement for any particular hair color. One exception is PERSON WITH BLOND HAIR, which needs to have blond hair regardless of skin tone.

To have an effect on an emoji, an emoji modifier must immediately follow that emoji. There is only one exception: there may be an emoji variation selector between them. The emoji modifier automatically implies the emoji presentation style, so the variation selector is not needed. However, if the emoji modifier is present it must come immediately after the modified emoji character, such as in:

<U+270C VICTORY HAND, FE0F, TYPE-3>

Any other intervening character causes the emoji modifier to appear as a free-standing character. Thus

![]() +

+ ![]() +

+ ![]() →

→ ![]()

![]()

Emoji for multi-person groupings present some special challenges:

The basic solution for each of these cases is to represent the

multi-person grouping as a sequence of characters—a separate

character for each person intended to be part of the grouping, along

with characters for any other symbols that are part of the grouping.

Each person in the grouping could optionally be followed by an emoji

modifier. For example, conveying the notion of COUPLE WITH HEART for

a couple involving two women can use a sequence with WOMAN followed

by an emoji-style HEAVY BLACK HEART followed by another WOMAN

character; each of the WOMAN characters could have an emoji modifier

if desired.

This makes use of conventions already found in current emoji usage, in which certain sequences of characters are intended to be displayed as a single unit.

Implementations can present the emoji modifiers as separate characters in an input palette, or present the combined characters using mechanisms such as long press.

The emoji modifiers are not intended for combination with arbitrary emoji characters. Instead, they are restricted to the following characters: no other characters are to be combined with emoji modifiers. This set may change over time, with successive versions of this document. To find the exact list of emoji modifier bases for each version, use the Emoji_Modifer_Base character property, as described in Annex A: Emoji Properties and Data Files.

The following chart shows the expected display with emoji modifiers, depending on the preceding character and the level of support for the emoji modifier. The “Unsupported” rows show how the character would typically appear on a system that does not have a font with that character in it: with a missing glyph indicator.

| Support Level | Emoji Modifier Base | Sequence | Display Color | Display B&W |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fully supported | Yes | |||

| No | ||||

| Fallback | Yes | |||

| No | ||||

| Unsupported | Yes | |||

| No |

The interaction between variation selectors and emoji modifiers is specified as follows:

| Variation Selector | Emoji Modifier | Result | Comment |

|---|---|---|---|

| None | Yes | Emoji Presentation | In the absence of other information, the emoji modifier implies emoji appearance. |

| Emoji (U+FE0F) | The emoji modifier base and emoji variation selector must form a valid variation sequence, and the order must as specified in emoji modifier sequence—otherwise support of the variation selector would be non-conformant. | ||

| Text (U+FE0E) | Text Presentation |

A supported emoji modifier sequence should be treated as a single

grapheme cluster for editing purposes (cursor moment, deletion,

etc.); word break, line break, etc. For input, the composition of

that cluster does not need to be apparent to the user: it appears on

the screen as a single image. On a phone, for example, a long-press on a human figure can bring up a minipalette of different skin tones,

without the user having to separately find the human figure and then

the modifier. The following shows some possible appearances:

on a human figure can bring up a minipalette of different skin tones,

without the user having to separately find the human figure and then

the modifier. The following shows some possible appearances:

or

|

||

Of course, there are many other types of diversity in human appearance besides different skin tones: Different hair styles and color, use of eyeglasses, various kinds of facial hair, different body shapes, different headwear, and so on. It is beyond the scope of Unicode to provide an encoding-based mechanism for representing every aspect of human appearance diversity that emoji users might want to indicate. The best approach for communicating very specific human images—or any type of image in which preservation of specific appearance is very important—is the use of embedded graphics, as described in Longer Term Solutions.

The U+200D ZERO WIDTH JOINER (ZWJ) can be used between the elements of a sequence of characters to indicate that a single glyph should be presented if available. An implementation may use this mechanism to handle such an emoji zwj sequence as a single glyph, with a palette or keyboard that generates the appropriate sequences for the glyphs shown. So to the user of such a system, these behave like single emoji characters, even though internally they are sequences.

When an emoji zwj sequence is sent to a system that does not have a corresponding single glyph, the ZWJ characters are ignored and a fallback sequence of separate emoji is displayed. Thus an emoji zwj sequence should only be defined and supported by implementations where the fallback sequence would also make sense to a recipient.

For example, the following are possible displays:

| Sequence | Display | Combined glyph? |

|---|---|---|

Yes |

||

No |

See also the chart containing Emoji ZWJ Sequences.

The use of ZWJ sequences may be difficult in some implementations, so caution should taken before adding new sequences.

For recommendations on the use of variation selectors in ZWJ sequences, see Section 2.4 Emoji Implementation Notes below.

Some changes to rules and data are needed for best segmentation behavior of additional emoji zwj sequences, prior to the eventual publication of Unicode 10.0. Such changes are planned for inclusion in CLDR Version 30.

The properties for TAG characters U+E0020..U+E007F (TAG SPACE..CANCEL TAG) have been modified for use in indicating variants of emoji characters. However, the fallback behavior of the TAG characters is not optimal. It is strongly recommented that any implementation mark a sequence of TAG characters after an emoji character or sequence with a distinctive appearance, such as modifying the image for that character or sequence by overlaying a question mark as shown below.

There are different ways to count the emoji in Unicode, especially since sequences of emoji may appear as single emoji image. The following provides an overview of the ways to count emoji. There is no single number; it can be (for example):

For example, there are only 26 Regional Indicator (RI) code points, which are used in pairs. Some of these pairs may be displayed as emoji flags, and others may not. There are 257 valid pairs that can be used to represent 257 regions. Single Regional Indicators are not used as emoji by themselves, so they are listed as "incomplete singletons" in the table below.

The following table provides more detail about the various counts as of Unicode 9.0:

| Type | Count | Subtotal |

|---|---|---|

| singletons | 1,123 | 1,123 |

| incomplete singletons (12 keycap base characters, 26 RI characters) | -38 | 1,085 |

| keycaps (sequences) | 12 | 1,097 |

| valid regional indicator sequences (a subset of these may be displayed as flags) | 257 | 1,354 |

| modifier sequences (skin tones) for 83 base characters | 415 | 1,769 |

| ZWJ sequences, e.g. for family combinations (platform-specific extensions) | 22 | 1,791 |

| ZWJ sequences that typically duplicate singletons (produce the same image as some singleton character) | -3 | 1,788 |

Separate Emoji Charts provide more information on many of these subsets and others, for example:

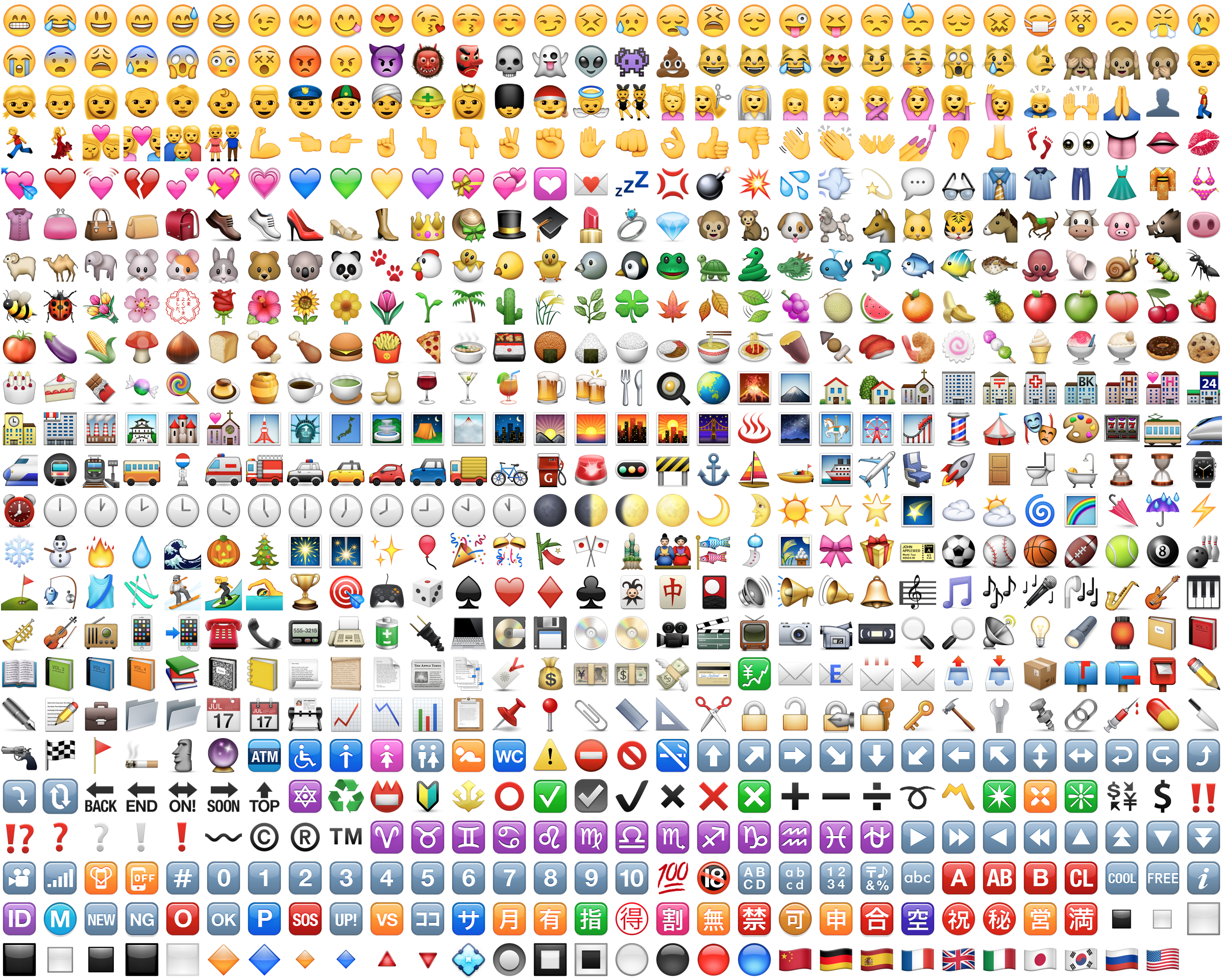

Historically, 722 Unicode emoji correspond to the Japanese carrier sets. Three of these are space characters in Unicode, which cannot have an emoji presentation. This leaves 719 emoji, shown below. The 10 emoji flags require 15 unique Regional Indicator characters (in 10 different pairs) for their representation. Most of the keycap emoji require use of COMBINING ENCLOSING KEYCAP in addition to the base character. Thus a total of 725 unique code points are used to represent these emoji.

|

There are another 247 flags (aside from the 10 from the Japanese carrier sets) that can be supported with Unicode 6.0 characters. No additional code points are needed for these, since they are combinations of Regional Indicator characters already encoded for the Japanese Carrier Emoji.

|

Some of these flags use the same glyphs. For more about flags, see Annex B: Flags.

Certain emoji have defined variation sequences, where an emoji character can be followed by one of two invisible emoji variation selectors:

This capability was added in Unicode 6.1. Some systems may also provide this distinction with higher-level markup, rather than variation sequences. For more information on these selectors, see Emoji Variation Sequences.

Implementations should support both styles of presentation for the characters with variation sequences, if possible. Most of these characters are emoji that were unified with preexisting characters. Because people are now using emoji presentation for a broader set of characters, Unicode 9.0 adds variation sequences for all emoji with default text presentation (see discussion below). These are the characters shown in the column labeled “Default Text Style; no VS in U8.0” in the Text vs Emoji chart.

However, even where the variation selectors exist, it had not been clear for implementers whether the default presentation for pictographs should be emoji or text. That means that a piece of text may show up in a different style than intended when shared across platforms. While this is all a perfectly legitimate for Unicode characters—presentation style is never guaranteed—a shared sense among developers of when to use emoji presentation by default is important, so that there are fewer unexpected and "jarring" presentations. Implementations need to know what the generally expected default presentation is, to promote interoperability across platforms and applications.

There had been no clear line for implementers between three categories of Unicode characters:

These categories can be distinguished using properties listed in Annex A: Emoji Properties and Data Files. The first category are characters with Emoji=Yes and Emoji_Presentation=Yes. The second category are characters with Emoji=Yes and Emoji_Presentation=No. The third category are characters with Emoji=No.

The presentation of a given emoji character depends on the environment, whether or not there is an emoji or text variation selector, and the default presentation style (emoji vs text). In informal environments like texting and chats, it is more appropriate for most emoji characters to appear with a colorful emoji presentation, and only get a text presentation with a text variation selector. Conversely, in formal environments such as word processing, it is generally better for emoji characters to appear with a text presentation, and only get the colorful emoji presentation with the emoji variation selector.

Based on those factors, here is typical presentation behavior. However, these guidelines may change with changing user expectations.

| Example Environment | with Emoji VS |

with Text VS |

with no VS |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

text-default |

emoji-default |

|||

| word processing | ||||

| plain web pages | ||||

| texting, chats | ||||

As of Unicode 9.0, every emoji character with a default text presentation allows for an emoji variation selector. Thus the presentation of these characters can be controlled on a character-by-character basis. The characters that can have emoji variation selectors applied to them are listed in Emoji Variation Sequences.

In addition, the next two sections describe two other mechanisms for globally controlling the emoji presentation: Using language tags with locale extensions, or using special script codes. Though these are new mechanisms and not yet widely supported, vendors are encouraged to support the locale extension for most general usage such as in browsers; the special script codes may be appropriate for more specific usage such as OpenType font selection, or in APIs. For more information, see [CLDR].

The locale extension “-em” can be used to specify desired presentation for characters that may have both text-style and emoji-style presentations available. There are three values that can be used, here illustrated with “sr-Latn”:

| Locale Code | Description |

|---|---|

| sr-Latn-u-em-emoji | use an emoji presentation for emoji characters where possible |

| sr-Latn-u-em-text | use a text presentation for emoji characters where possible |

| sr-Latn-u-em-default | use the default presentation (only needed to reset an inherited -em setting). |

This can be used in HTML, for example, with

<html lang="sr-Latn-u-em-emoji">.

Note that this approach does not have the disadvantages listed below

for the script-tag approach.

Two script subtags can be used to control the presentation style. These use script codes defined by ISO 15924 but given more specific semantics by CLDR, see unicode_script_subtag:

These script codes are not suitable for use in general language tags:

However, they may be useful by themselves in specific contexts such as OpenType font selection, or in APIs that take script codes.

Other approaches for control of emoji presentation are also in use. For example, in some CSS implementations, if any font in the lookup list is an emoji font, then emoji presentation is used whenever possible.

Neither the Unicode code point order, nor the standard Unicode Collation ordering (DUCET), are currently well suited for emoji, since they separate conceptually-related characters. From the user's perspective, the ordering in the following selection of characters sorted by DUCET appears quite random, as illustrated by the following example:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The emoji-ordering chart file shows an ordering for emoji characters that groups them together in a more natural fashion. This data has been incorporated into [CLDR].

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

This ordering groups characters presents a cleaner and more expected ordering for sorted lists of characters. The groupings include: faces, people, body-parts, emotion, clothing, animals, plants, food, places, transport, and so on. The ordering also groups more naturally for the purpose of selection in input palettes. However, for sorting, each character must occur in only one position, which is not a restriction for input palettes. See Section 6 Input.

Emoji are not typically typed on a keyboard. Instead, they are

generally picked from a palette, or recognized via a dictionary. The

mobile keyboards typically have a ![]() button to select a palette

of emoji, such as in the left image below. Clicking on the

button to select a palette

of emoji, such as in the left image below. Clicking on the ![]() button reveals a palette, as in the right image.

button reveals a palette, as in the right image.

|

|

The palettes need to be organized in a meaningful way for users. They typically provide a small number of broad categories, such as People, Nature, and so on. These categories typically have 100-200 emoji.

Many characters can be categorized in multiple ways: an orange is both a plant and a food. Unlike a sort order, an input palette can have multiple instances of a single character. It can thus extend the sort ordering to add characters in any groupings where people might reasonably be expected to look for them.

More advanced palettes will have long-press enabled, so that people can press-and-hold on an emoji and have a set of related emoji pop up. This allows for faster navigation, with less scrolling through the palette.

Annotations for emoji characters are much more finely grained

keywords. They can be used for searching characters, and are often

easier than palettes for entering emoji characters. For example, when

someone types “hourglass” on their mobile phone, they could see and

pick from either of the matching emoji characters ![]() or

or ![]() . That is often much easier than scrolling through

the palette and visually inspecting the screen. Input mechanisms may

also map emoticons to emoji as keyboard shortcuts: typing

:-) can result in

. That is often much easier than scrolling through

the palette and visually inspecting the screen. Input mechanisms may

also map emoticons to emoji as keyboard shortcuts: typing

:-) can result in ![]() .

.

In some input systems, a word or phrase bracketed by colons is used

to explicitly pick emoji characters. Thus typing in “I saw an :ambulance:”

is converted to “I saw an ![]() ”. For completeness,

such systems might support all of the full Unicode names, such as :first

quarter moon with face: for

”. For completeness,

such systems might support all of the full Unicode names, such as :first

quarter moon with face: for ![]() . Spaces within the phrase

may be represented by _, as in the following:

. Spaces within the phrase

may be represented by _, as in the following:

“my :alarm_clock: didn’t work”

→

“my ![]() didn’t work”.

didn’t work”.

However, in general the full Unicode names are not especially suitable for that sort of use; they were designed to be unique identifiers, and tend to be overly long or confusing.

Searching includes both searching for emoji characters in queries,

and finding emoji characters in the target. These are most useful

when they include the annotations as synonyms or hints. For example,

when someone searches for ![]() on yelp.com

on yelp.com ,

they see matches for “gas station”. Conversely, searching for “gas

pump” in a search engine could find pages containing

,

they see matches for “gas station”. Conversely, searching for “gas

pump” in a search engine could find pages containing ![]() . Similarly, searching for “gas pump” in an email

program can bring up all the emails containing

. Similarly, searching for “gas pump” in an email

program can bring up all the emails containing ![]() .

.

There is no requirement for uniqueness in both palette categories and

annotations: an emoji should show up wherever users would expect it.

A gas pump ![]() might show up under “object” and

“travel”; a heart

might show up under “object” and

“travel”; a heart ![]() under “heart” and

“emotion”, a

under “heart” and

“emotion”, a ![]() under “animal”, “cat”, and “heart”.

under “animal”, “cat”, and “heart”.

Annotations are language-specific: searching on yelp.de ,

someone would expect a search for

,

someone would expect a search for ![]() to result in matches for “Tankstelle”. Thus

annotations need to be in multiple languages to be useful across

languages. They should also include regional annotations within a

given language, like “petrol station”, which people would expect

search for

to result in matches for “Tankstelle”. Thus

annotations need to be in multiple languages to be useful across

languages. They should also include regional annotations within a

given language, like “petrol station”, which people would expect

search for ![]() to result in on yelp.co.uk

to result in on yelp.co.uk .

An English annotation cannot simply be translated into different

languages, since different words may have different associations in

different languages. The emoji

.

An English annotation cannot simply be translated into different

languages, since different words may have different associations in

different languages. The emoji ![]() may be associated with Mexican or Southwestern restaurants in the US,

but not be associated with them in, say, Greece.

may be associated with Mexican or Southwestern restaurants in the US,

but not be associated with them in, say, Greece.

There is one further kind of annotation, called a TTS name,

for text-to-speech processing. For accessibility when reading text,

it is useful to have a short, descriptive name for an emoji

character. A Unicode character name can often serve as a basis for

this, but its requirements for name uniqueness often ends up with

names that are overly long, such as black right-pointing

double triangle with vertical bar for ![]() .

TTS names are also outside the current scope of this document.

.

TTS names are also outside the current scope of this document.

The longer-term goal for implementations should be to support embedded graphics, in addition to the emoji characters. Embedded graphics allow arbitrary emoji symbols, and are not dependent on additional Unicode encoding. Some examples of this are found in Skype and LINE—see the emoji press page for more examples.

However, to be as effective and simple to use as emoji characters, a full solution requires significant infrastructure changes to allow simple, reliable input and transport of images (stickers) in texting, chat, mobile phones, email programs, virtual and mobile keyboards, and so on. (Even so, such images will never interchange in environments that only support plain text, such as email addresses.) Until that time, many implementations will need to use Unicode emoji instead.

For example, mobile keyboards need to be enhanced. Enabling embedded

graphics would involve adding an additional custom mechanism for

users to add in their own graphics or purchase additional sets, such

as a ![]() sign to add an image to

the palette above. This would prompt the user to paste or otherwise

select a graphic, and add annotations for dictionary selection.

sign to add an image to

the palette above. This would prompt the user to paste or otherwise

select a graphic, and add annotations for dictionary selection.

With such an enhanced mobile keyboard, the user could then select those graphics in the same way as selecting the Unicode emoji. If users started adding many custom graphics, the mobile keyboard might even be enhanced to allow ordering or organization of those graphics so that they can be quickly accessed. The extra graphics would need to be disabled if the target of the mobile keyboard (such as an email header line) would only accept text.

Other features required to make embedded graphics work well include the ability of images to scale with font size, inclusion of embedded images in more transport protocols, switching services and applications to use protocols that do permit inclusion of embedded images (eg, MMS versus SMS for text messages). There will always, however, be places where embedded graphics can’t be used—such as email headers, SMS messages, or file names. There are also privacy aspects to implementations of embedded graphics: if the graphic itself is not packaged with the text, but instead is just a reference to an image on a server, then that server could track usage.

The following four binary character properties are available for emoji characters. These are not formally part of the Unicode Character Database (UCD), but share the same namespace and structure.

| Property | Property Values |

|---|---|

| Emoji | =Yes for characters that are emoji =No otherwise |

| Emoji_Presentation | =Yes for characters that have emoji

presentation by default =No otherwise |

| Emoji_Modifier | =Yes for characters that are emoji

modifiers =No otherwise |

| Emoji_Modifier_Base | =Yes for characters that can serve as a

base for emoji modifiers =No otherwise |

If Emoji=No, then Emoji_Presentation=No, Emoji_Modifier=No, and Emoji_Modifier_Base=No.

The property values are specified in the main data file; see [emoji-data]. The format for that file is described in its header. There are two other data files listing sequences used to represent emoji.

See [emoji-charts] for a collection of charts that have been generated from the emoji data file that may be useful in helping to understand it and the related [CLDR] emoji data (annotations and ordering). These charts are not versioned, and are purely illustrative; the data to use for implementation is in [emoji-data].

26 REGIONAL INDICATOR symbols are used in pairs to represent regions; these pairs are generally displayed as flags in systems that support them as emoji. Only valid sequences should be used, where:

Some region sequences represent countries (as recognized by the United Nations, for example); others represent territories that are associated with a country. Such territories may have flags of their own, or may use the flag of the country with which they are associated.

Caveats:

For additional information see the sub-section on Regional Indicator Symbols in Section 22.10 Enclosed and Square of [Unicode].

Emoji are generally presented with a square aspect ratio, which presents a problem for flags. The flag for Qatar is over 150% wider than tall; for Switzerland it is square; for Nepal it is over 20% taller than wide. To avoid a ransom-note effect, implementations may want to use a fixed ratio across all flags, such as 150%, with a blank band on the top and bottom. (The average width for flags is between 150% and 165%.) Presentation as a “waving” flag, or clipping to a circle, can help to present a uniform appearance, masking the aspect differences.

Flags should have a visible edge. One option is to use a 1 pixel gray line chosen to be contrasting with the adjacent field color.

For an open-source set of flag images (png and svg), see region-flags .

.

Options for presenting an emoji_flag_sequence for which a system does not have a specific flag or other glyph include:

The code point order of flags is by region code, which will not be intuitive for viewers, since that rarely matches the order of countries in the viewer's language. English speakers are surprised that the flag for Germany comes before the flag for Djibouti. An alternative is to present the sorted order according to the localized country name, using [CLDR] data.

Mark Davis and Peter Edberg created the initial versions of this document, and maintain the text.

Thanks to Shervin Afshar, Julie Allen, Jeremy Burge, Michele Coady, Chenjintao (陈锦涛), Chenshiwei, Peter Constable, Craig Cummings, Andrew Glass, Paul Hunt, Hiroyuki Komatsu, Norbert Lindenberg, Ken Lunde, Gwyneth Marshall, Rick McGowan, Katsuhiko Momoi, Katsuhiro Ogata, Katrina Parrott, Michelle Perham, Addison Phillips, Roozbeh Pournader, Judy Safran-Aasen, Markus Scherer, Richard Tunnicliffe, and Ken Whistler for feedback on and contributions to this document, including earlier versions.

Thanks to Adobe / Paul Hunt, Apple, Michael Everson, Google, Microsoft, and iDiversicons for supplying images for illustration.

The content for this section has been moved to Emoji Images and Rights.

The following summarizes modifications from the previous revisions of this document.

Revision 7

Modifications for previous revisions are listed in the previous version of this document.

© 2016 Unicode, Inc. All Rights Reserved. The Unicode Consortium makes no expressed or implied warranty of any kind, and assumes no liability for errors or omissions. No liability is assumed for incidental and consequential damages in connection with or arising out of the use of the information or programs contained or accompanying this technical report. The Unicode Terms of Use apply.

Unicode and the Unicode logo are trademarks of Unicode, Inc., and are registered in some jurisdictions.