This is something I wrote in 2015 and I have noticed that it's been getting a few hits recently. So I had a look and re-read it myself - and as I found it interesting I thought it needed another outing; so I hope you enjoy it and think it worth it.

The Siege of the 'Four Courts' Dublin 1922

The Siege of the 'Four Courts' Dublin 1922

It's

been 24 years since my dad died and on the day he died I had to drive

up to my parents' bungalow in Northampton.

Now

for my American friends who have a different meaning for the word

bungalow, I have to explain over here it means something different

from over there.

The

word comes from India, as do so many of our

words: shampoo, pundit etc, in fact

bungalow is a Hindi word which, I reckon is the most

popular language in India; Roman Hindi, I would say,

as far as I remember, and the Indian meaning has it as a single

storey house, surrounded by a veranda – that sounds Indian too

doesn't it.

Over

here it's just a single storey house - just like the 'Craftsmen's

Houses' in Los Angeles.

My

mother suffered from Parkinson's and very bad arthritis, in fact she

needed constant looking after and up to that time had been cared for

by my dad and as is usually the case, the carer died first – and he

did.

Dropped

dead one day, as we say brown bread.

My

dad died in March, one day before his birthday, and the time between

that and the date she moved in with us was under seven months – but

it seemed like a year and a half.

I

would stay with her a couple of days a week and our daughter would

look after her when I wasn't there – but she couldn't be left alone

as she would try things like getting up out of her chair and falling.

So I

would sleep in the bed next to her – they had a couple of twin

beds.

They

were the same twin beds that my brother and I slept in as teenagers

but instead of looking over and seeing the brud – I saw the mater!!

Most

nights she would talk in her sleep.

Even

though she had Parkinson's she had very clear speech and a very

attractive Dublin accent with a huge vocal range.

Some

of the nights she went back to 1922 Dublin when she was Esther Tuite

– or Essie, as she called herself.

She

would call out in the middle of the night things like 'I'm only

looking – I live here; no I'm only looking. I live here – Parnell

Street!'

'Okay,

okay – I'll get back in.'

I

knew she was back in 1922 and I knew she was troubled.

After

she came to live with us I went in to her room one day and she was in

a coma; I couldn't wake her.

I

called my wife, who was a nurse at the time, and we called the doctor

who called the hospital and an ambulance came and took her away.

I

went with her, of course, and eventually left her in their care.

The

next day I got an early call from the hospital telling me to come in

as the position had turned worse.

On

the way there the radio played Louis Armstrong singing What a

Wonderful World' and the weather was beautiful and even

though I had already liked the song it has meant a lot more to me

ever since and every time I hear it I think of that day.

When

we got there she had 'come around' and for some reason she was

walking.

She

had a twinkle in her eye as she came and sat with us and I asked her

who she was and she said 'I'm Essie Tuite of Parnell Street.'

She

said that as if she was wondering why I had asked it; and why

shouldn't she; she seemed very cheeky and flirty and I kind of got to

know that side of my mother a bit; I was looking forward to meeting

her again but she went back into a coma a couple of times,

introducing me to other aspects of her inner personality and history

and when she was discharged she was, more or less, the same as she

had been before she went in - only this time she couldn't walk at

all.

I

told her all about the Essie Tuite history bits and

she told me the following.

Because

I am the way I am and I doodle I aye, I wrote a lot of it

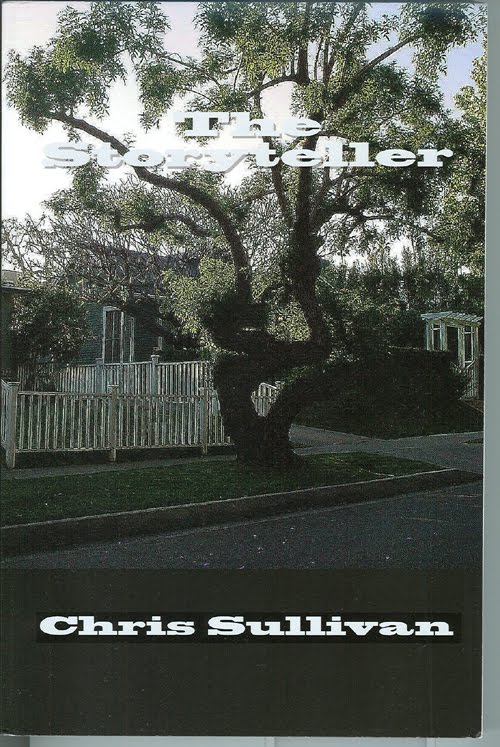

down and even used some of it in my first novel Alfredo

Hunter: the Man With the Pen.

I

often felt a bit of a cheat but as it seemed to catch the Dublin

dialect and accent together with an eye witnessed account of the

facts of the time, one of the most important times in Irish history,

I don't feel guilty at all.

If

you have any kind of artist in the family – writer, actor, painter

and the like, you are bound to be used and you'll know what I mean.

Some

of the names have been changed to protect the innocent but – they

were all innocent, let's face it.

She

started off by telling me how she met my dad.

We

met at McCann's pub. I was outside with Maura Short sheltering from

the rain and he came out and told us to move on. He was working in

there as a barman. There wasn't a pick on him. He was just like

number one.”

She

held one finger up.

He

was an awful looking yoke. It was just after I left home. My father

was a bastard. Here was I at twenty five and he wanting me in by

ten-o-clock. I moved in with Maura Short. They were looking after me.

My

father was in the British Army and knew nothing about the Easter

uprising - he was away getting gassed. (In the Somme) I

remember everything about it; the lot.

People

don't believe me, you know, but I do. I remember the Fourcourts.

I

think it was the IRA that was in the Fourcourts...think it was......

They came and knocked the door – the British army - and told us not

to be frightened of the bomb. Anyway ...my mother said – ‘Oh

Jesus, Mary and Joseph: you're not going to kill the poor men that's

in there?’

They

said ‘Well if they don't come out - and it's war missus - we'll

have to.’

They

never came out; they were blown up - and what was left of them put

their mate on a stretcher - the door it was a door it was - and they

walked down Parnell Street to the Castle. They were singing:

We

fight for Ireland,

Dear

Old Ireland

Ireland

Boys away.”

“And

the British soldiers were all on edge but they never touched them.

They carried their oul' comrade - wouldn't let one of them touch

them, like you know? I couldn't have lived anywhere else worse than

Parnell Street when the nineteen hundred and....when the troubles

were on.”

She

sat there thinking and I could actually see a thought enter her head

by the expression on her face; then she laughed.

“We

had - in Parnell Street - it was the one yard for the two houses and

it was a door that went through to the yard and over the wall you

went and you were at a hill and you were away.

“This

bloke was standing at the door - Parnell Street, you know - and

another bloke was with him and ran away shouting ‘British Bastard’

and with that the what-you-call-him? - The

Black and Tan followed

and, of course, he disappeared over the back. But the Black and Tan

came straight up through the houses - never knocked on the door -

just opened it. Could be standing there in your nod for all they

cared. They said ‘Hello Pop’ - of course my grandfather being old

with the beard.

My

father was a British soldier at the time and they thought we were all

British. And my father's father had a red white and blue flag hanging

through the window; they all stuck flags out. The old bastard was in

the British army my father; but he used to come home on leave and go

across to the pub with my Uncle Stephen and my Grandfather.

Uncle

Tom was posh; he only used to drink wine; port wine. And he used to

wear spats on his shoes; he was the posh one of the family. And if

they had have done right with him he would have been a millionaire

today - if he'd have lived.”

“If

he’d have lived he would have been a hundred and forty.” I said.

She

laughed again and started to cough; I gave her a drink of water. She

took a drink and carried on:

“He

started a factory. Done a lot of pinching out of the other factory -

my Grandfather owned a part share in it - Lymon's - and they were

starting their own place: Lymon's sweet factory in O'Connell Street.

My Uncle Tom was to go out and look for orders. Sure my Uncle Stephen

drank it all; he couldn't be kept out of the pub. He was in the IRA

and went to prison. Uncle Tom went too but they were in different

places.

I

have such a good memory - people think I'm mad when I tell them

things. Grandfather Shea was in the IRA. He was a proper rebel my

Grandfather was. But my father and his father were no bleedin' good.

They were oul' feckin' British soldiers.

Grandfather

Shea was lovely; he used to keep his revolver on the ledge in his

room – the room at our house. It was a bit of luck nobody ever

found it.

My

father used to whip me and Grandfather Shea found out - 'I'll take

his bleedin' life...’ not bleedin' - they never used bleedin' ‘Take

his bloody life if you touch her again.’

To my

father he said that.”

She

paused again and looked into the cardboard fire. Strange the way

things were - she had brought with her an electric fire with a

cardboard fire effect.

“We

went to live in Marino when I was ten. Our Kathleen was born - she

was born in March Kathleen was and she was a new baby when we went to

live in Marino. I remember I had one frock on me all day and Kathleen

was a baby in my arms. And my whole frock was stained from where she

shit - it wasn't shit - it was just the mark.

The

one thing my father did for me – the only thing he ever got me

during his life - was to buy me a bike – the only thing he ever did

- says he 'I'll buy you a bicycle.'

He

brought me into a shop on the quay and says he ‘Get up and ride

it.’

I

couldn't ride the bloody thing – I’d told him I could ride a

bike. And my father went up and down the alley for to show me how to

ride.

Kings

End Street was another street where we used to go to learn how to

ride the bike. One day we were coming down from Capel Street right

down to Parnell Street to Henry Street. There was a private car stood

there and didn't I run into the bloody side of the car. All I could

hear my father say was ‘Get up quick. Come on get up.’

I

burst the whole side of the bloody car.” She laughed:

“I

was the first one in our street to have a bike. But I was never let

out to play. The nuns wouldn't let you. You weren't allowed to play

in the street.

When

my grandfather was the age I am now he lived with us in Marino –

one day he had a row with my father. He never liked my father cos my

da got my mother into trouble. My Mother was married in August and I

was born in the October.

When

they had the row my Grandfather got up - he had one of his turns -

dying you know - he said ‘I'm not going to live here any more’

and he got a pair of sticks and he walked up to the entrance, you

know, and I kept saying and crying ‘Come on home, Granda, come on

home;’ The poor fella was dying. They could at least have made him

feel wanted.

But

he wouldn't come home; he wanted Locky - that was the cabman that he

latched on to no matter where he was going. No matter where he was

going he sent for Locky; he took us to the boat at the North Wall one

day when we were going to the Isle of Mann for a holiday; me and my

grandfather. And he got us on the boat and my grandfather told Locky

to come and fetch us and pick us up Friday at a certain time.

Poor

oul' grandfather didn't know about having to book lodgings. He

couldn't get any; we had to come back.”

Such

is life.

Sometimes things can be forgotten; little things but once in a while I write things down and when I find them again, years later, they are like pieces of treasure. Try it sometime.

Sometimes things can be forgotten; little things but once in a while I write things down and when I find them again, years later, they are like pieces of treasure. Try it sometime.

Countess Constance Markievicz in Dublin 1922

Countess

Markievicz (nee Gore Booth) was a very important figure in Irish

History; for a start off she was the first female MP voted in to the

British House of Commons - although as with Sinn

Féin she never took her seat in the

commons.

Constance

Georgine Markievicz, Countess Markievicz was an Irish Sinn Féin and

Fianna Fáil politician, revolutionary nationalist, suffragette and

socialist. Wikipedia