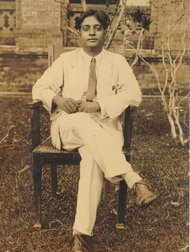

Courtesy of Falguni Sarkar/The S.N. Bose

ProjectSatyendra Nath Bose at Dacca University (now

Dhaka) in Bangladesh in the 1930s.

In the word “boson,” as media reports have plentifully pointed out during the

past two days, is contained the surname of Satyendra Nath Bose, the Calcutta

physicist who first mathematically described the class of particles to which he

gave his name. As was common with Indian scientists in the early 20th century,

however, his work might easily have eluded international recognition. Like the

mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujam, Mr. Bose was saved from obscurity by a

generous and influential mentor in Europe. In Mr. Bose’s case, that mentor

turned out to be one of the greatest physicists of them all: Albert

Einstein.

In 1921, Mr. Bose moved from the faculty of the University of Calcutta to

that of the University of Dhaka. He had already published papers with his friend

and colleague Meghnad Saha, working particularly equations of state, which

describe how matter behaves under differing sets of physical conditions. Mr.

Bose was not entirely happy in Dhaka at first. A month after he moved, he wrote

to Mr. Saha:

Work has not yet started. [The university has] quite a few things but due

to utter neglect they are in a bad way. Perhaps I need not elaborate. On the

table of the sahibs are scattered lots of Nicol prisms, lens and eye-pieces. It

would require a lot of research to determine which one belongs to which

apparatus. We do suffer from a lack of journals here, but the authorities of the

new university have promised to place orders for some of them along with their

back numbers. Talk is going on about having a separate science

library.

After he settled in, Mr. Bose began to worry away at the intricacies of

black-body radiation. In 1918, Max Planck had won the Nobel Prize in physics for

discovering that objects emit radiation in discrete packets of energy, called

quanta; he had also set down an equation governing this process. But as C.S.

Unnikrishnan, a professor at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research told me,

Mr. Bose was troubled by a perceived inconsistency in Mr. Planck’s process.

“These quanta were treated as particles of light, but the equation

simultaneously assumed that radiation was behaving like waves,” Mr. Unnikrishnan

said. “Somewhere this was cheating – that was Bose’s impression. So he had to

invent a way of counting the particles in a ‘gas’ of light, at various possible

energy states, and still have Planck’s law hold good. He was reverse-engineering

Planck’s equation, in a way.”

Much later, in 1970, Mr. Bose would tell an interviewer named Jagdish

Mehra:

As a teacher who had to make these things clear to his students, I was

aware of the conflicts involved and had thought about them. I wanted to know how

to grapple with the difficulty in my own way. It was not some teacher who asked

me to go and solve this little problem. I wanted to know. And that led me to

apply statistics.

The paper he wrote, titled “Planck’s Law and the Light-Quantum Hypothesis,”

was first rejected by a referee at the London-based journal named Philosophical

Magazine, which had published some of Mr. Bose’s previous papers. Undeterred,

Mr. Bose sent it, in the summer of 1924, to Berlin, to the desk of Mr. Einstein,

who had won his own Nobel three years earlier. Mr. Einstein received dozens of

such manuscripts every day, and he was already turning away from the field of

quantum mechanics to work out larger unified theories. (In “Subtle is the Lord,”

Abraham Pais noted that “Einstein said of his work in quantum statistics,

‘That’s only by the way.’”) But perhaps something about Mr. Bose’s accompanying

letter caught Einstein’s eye:

Respected Master,

I have ventured to send you the accompanying article

for your perusal and opinion. I am anxious to know what you think of it… I do

not know sufficient German to translate the paper. If you think the paper worth

publication I shall be grateful if you arrange for its publication in

Zeitschrift fur Physik. Though a complete stranger to you, I do not feel any

hesitation in making such a request. Because we are all your pupils though

profiting only by your teachings through your writings. I do not know whether

you still remember that somebody from Calcutta asked your permission to

translate your papers on Relativity in English. You acceded to the request. The

book has since been published. I was the one who translated your paper on

Generalised Relativity.

Yours faithfully

S. N. Bose

Courtesy of Falguni Sarkar/The S.N. Bose

ProjectA passport photograph of Satyendra Nath Bose

taken before he left for Europe in 1924 where he met Albert

Einstein.

Mr. Einstein did indeed think the paper worth publication. Within a month, he

had translated and submitted it to Zeitschrift für Physik, appending a note at

the end of its four concise, equation-filled pages: “In my opinion Bose’s

derivation signifies an important advance.” Mr. Einstein would take Mr. Bose’s

work further still, applying his statistical techniques to “count” atoms in an

ordinary gas, and to discover the low-energy states of particles in the

supercooled gases known now as Bose-Einstein Condensates.

The publication of this paper – and Mr. Einstein’s championing of it – earned

Mr. Bose a two-year leave of absence to conduct research in Europe. His

university had been reluctant to grant him this leave, but when Mr. Einstein

sent him a hand-written postcard acknowledging the importance of his

contribution, “it solved all problems,” Mr. Bose told Mr. Mehra, who wrote a

short biography of him for the Royal Society in 1975. “That little thing gave me

a sort of passport to the study leave. They gave me leave for two years and

rather generous terms. I received a good stipend. They also gave a separation

allowance for the family, otherwise I would not have been able to go abroad at

all. … Then I also got a visa from the German Consulate just by showing them

Einstein’s card. They did not require me to pay the fee for the visa!”

In Paris, Mr. Bose worked with Maurice de Broglie and Marie Curie, armed with

letters of introduction from a French Indologist named Paul Langevin. “She was

very nice,” he told Mr. Mehra about Ms. Curie. “I told her that I would remain

in Paris about six months and learn French well, but I wasn’t able to tell her

that I knew sufficient French already and could manage to work in her

laboratory. She preferred to have her own ideas and told me that I better be

around a long time, not hurry, and concentrate on the language.”

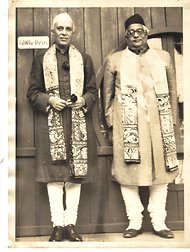

Courtesy of Falguni Sarkar/The S.N. Bose

ProjectFormer prime minister Jawaharlal Nehru, left,

and Satyendra Nath Bose at the Visva-Bharati University, Santiniketan, West

Bengal. Mr. Bose was the vice chancellor of the university between

1956-1959.

Mr. Bose met Mr. Einstein only in late 1925, in Berlin. That meeting, he

recalled, “was most interesting. He wanted to know how I had hit upon the idea

of deriving Planck’s law in this way. Then he challenged me. He wanted to find

out whether my hypothesis…did really mean something novel about the interaction

of quanta, and whether I could work out the details of this business.” These

were momentous meetings for Mr. Bose. In 1972, in the American Journal of

Physics, William Blanpied wrote after an interview with Mr. Bose: “Even more

than forty years later, one still has the impression that the young Bose was

terribly intimidated by Europeans… The nature of British rule in India…had the

effect of making the subject people believe that they really were inferior.”

Returning to Dhaka in 1926, Mr. Bose earned a professorship in physics, but

he did not publish for a long time thereafter. His interests wandered – over the

constantly shifting terrain of physics, but also into other fields, such as

philosophy, anthropology, literature and the surging Indian independence

movement. Only in 1937 did he publish his next physics paper; in the early

1950s, he worked on unified field theories, into which Mr. Einstein had thrown

himself so completely, but these were hardly groundbreaking. “I was not really

in science anymore,” Mr. Bose would tell Mr. Mehra, “I was like a comet, a comet

which came once and never returned again.”