Home - Search - Browse - Alphabetic Index: 0- 1- 2- 3- 4- 5- 6- 7- 8- 9

A- B- C- D- E- F- G- H- I- J- K- L- M- N- O- P- Q- R- S- T- U- V- W- X- Y- Z

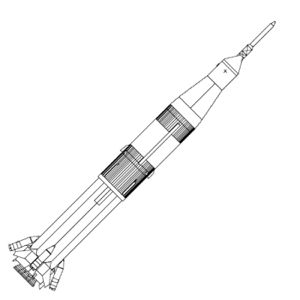

Saturn I

Saturn 1 Geneology

Credit: © Mark Wade

AKA: Juno V;Saturn C-1. Status: Retired 1975. First Launch: 1963-03-28. Last Launch: 1965-07-30. Number: 7 . Payload: 9,000 kg (19,800 lb). Thrust: 6,690.00 kN (1,503,970 lbf). Gross mass: 509,660 kg (1,123,600 lb). Height: 55.00 m (180.00 ft). Diameter: 6.52 m (21.39 ft). Apogee: 185 km (114 mi).

The Saturn launch vehicle was the penultimate expression of the Peenemuende Rocket Team's designs for manned exploration of the moon and Mars. The designs were continuously developed and improved, starting from the World War II A11 and A12 satellite and manned shuttle launcher, through the designs made public in the Collier's Magazine series of the early 1950's, until the shock of the first Sputnik launch brought sudden real interest from the U.S. government. On December 30 1957 Von Braun produced a 'Proposal for a National Integrated Missile and Space Vehicle Development Plan'. This had the first mention of a 1,500,000 lbf booster (Juno V, later Saturn I). By July of the following year Huntsville had in hand the contract from ARPA to proceed with design of the Juno V.

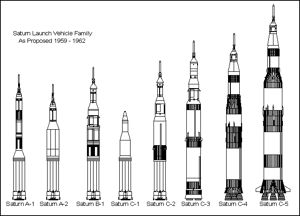

Following transfer of the Peenemuende Rocket Team from the US Army to NASA, a year after the first plan was mooted, Von Braun briefed NASA on plans for booster development at Huntsville with objective of manned lunar landing. It was initially proposed that 15 Juno V (Saturn I) boosters assemble a 200,000 kg payload in earth orbit for direct landing on moon. NASA produced two months later, on February 15, 1959, its plan for development in the next decade of Vega (later cancelled after NASA discovered the USAF was secretly developing the similar Hustler (Agena) upper stage), Centaur, Saturn, and Nova launch vehicles (Juno V renamed Saturn I at this point). Throughout the initial planning, Presidential decision, and landing mode debate for the Apollo lunar landing goal, a variety of Saturn and Nova configurations were considered. Of these, only the C-1 and C-5 were taken through to further development.

The political maneuvering that resulted in the Saturn I configuration is described by ABMA commander Medaris in his autobiography:

We had gone through the whole process of selecting upper stages and had made our recommendations to ARPA. We had indicated very clearly that we were willing to accept either the Atlas or Titan as the basis for building the second stage. The real difference was that in one case we would be using the Atlas engines and associated equipment, built by North American, while in the other case, we would be using the Titan power plant built by Aerojet. Largely because of the multitude of different projects that had been saddled on the Atlas, we favor the Titan. Convair builds the Atlas, and we had great confidence in Convair's engineering, but this was over shadowed in our mind by the practical difficulties of getting enough Atlas hardware. However, we assured ARPA that we would take either one.In the event, neither the Saturn A-1 or the Titan C went ahead. After several twists and turns, the Saturn I with the 160-inch upper stage was developed, the second production lot even being configured for Dynasoar. However Dynasoar was finally slated to fly on the Titan 3C, a third alternative in the USAF SLV-4 competition of 1961. Dynasoar in turn was cancelled, and the Saturn I was superseded by the Saturn IB for manned earth-orbit Apollo flights. Only the Titan 3C and its descendants would soldier on into the 21st Century, as the heavy-lift mainstay of American expendable boosters.The time scale was important. In order to get an operational vehicle in the air as soon as possible, and be able to match and possibly exceed Russia's capabilities, we recommended that the first flying vehicle to be made up of Saturn as the first stage and a second stage built with a Titan power plant. We also recommended using the tooling available at Martin for the airframe. We felt that by the time we got through the second-stage tests, the powerful new Centaur oxygen-hydrogen engine would be in good enough shape to become the third stage. We then calculated that a, year afterwards, or perhaps a little later, could begin to come up with a second-generation satellite vehicle that would cluster the Centaur engine for second stage.

Our people made extensive presentations to ARPA and NASA during the late spring of 1959, always taking the position that we could work with either combination that was agreed to by both. We were anxious to have them agree, because it seemed obvious to us that the nation could not afford more than one very large booster project. We believed that the resulting vehicle would be enormously useful both to the Defense Department for advanced defense requirements, and NASA for its scientific and civilian exploration of space.

We finally got a decision. - - We were told that we could begin designing the complete vehicle along the lines that we had recommended, namely, with the Titan as the basis for the second stage. So far there was no sign of trouble. Remembering the difficulties that we had had in connection with our requirements for North American engines for Jupiter, with the North American people largely under control of the Air Force, we knew that if we were to get on with the job properly we had to make our contract direct with Martin for the second stage work, and with the Convair-Pratt & Whitney group for the adaptation of Centaur to the third stage. We asked the Air Force for clearance to negotiate these matters with the companies concerned The Air Force (BMD) refused, and insisted that we let them handle all areas with the contractor. They used the old argument that they as a group could handle the responsibility much better, and that if they didn't handle it, there were bound to be priority problems connected with the military programs for Titan and others. We knew that the Air Force had no technical capacity of their own to put into this project, and that if we gave them the whole job, they would be forced to use the Ramo-Wooldridge organization, now known as the Space Technology Laboratories, as their contract agent to exercise technical supervision and co-ordination. While we knew and respected a few good men in STL, we felt we had ample cause to lack confidence in the organization as such. As a matter of fact, when the House Committee on Government Operations looked askance at STL with respect to their position as a profit-making organization, some of the best men had left the organization. We threw this one out on the table and said that we would not, under any circumstances, tolerate the interference of STL in this project. We knew that we had all the technical capability that was needed to supervise the overall system, and could not stand the delays and arguments that would most assuredly result were that organization to be thrown in also. Both sides presented their arguments to ARPA�Mr. Roy Johnson ruled that we could go ahead and contract directly Martin and others as required. It is understandable that the Air Force took this decision with poor grace. It represented a major setback to the system of absolute control over their own contractors, no matter for whom those contractors happened to be doing work. It also left them pretty much on the side- lines with respect to major participation in or control over any portion of the Saturn as a space vehicle.

With the amount of money still available to us from fiscal year 1960 and with our authorization from ARPA, we proceeded immediately to negotiate engineering contracts with Martin. We thought that since Mr. Johnson had complete control over this program, we had gotten over the last important hurdle and could get on about our business. Little did we realize the hornet's nest that had been stirred up, and less did we realize that winning that battle was finally to mean that we would lose the war, and would lose von Braun's entire organization.

We had only a few weeks of peace and quiet. From events that occurred later, I think I can make a fair estimate of what happened during this short period. Having been overruled by Johnson, the Air Force took a new approach. They decided that in view of the importance and power that was given the Deputy Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering by the 1958 changes in the defense organization, Dr. York represented their best avenue of approach through which to get back in the war.

For reasons of economy we had recommended, and it had been approved, that in building the second stage, we would use the same diameter as the Titan first stage -- 120 inches. The major costs of tooling for the fabrication of missile tanks and main structure is related to the diameter. Changes in length cost little or nothing in tooling. How the tanks are divided internally, or the structure reinforced inside, or the kind of structural detail that is used at the end in order to attach the structure to a big booster below, or to a different size stage above, have very little effect on tooling problems. However, a change in diameter sets up a major question of tools, costs, and time.

Suddenly, out of the blue came a directive to suspend work on the second stage, and a request for a whole new series of cost and time estimates, including consideration of increasing the second stage diameter to 160 inches. It appeared that Dr. York had entered the scene, and had pointed up the future requirements of Dynasoar as being incompatible with the 120-inch diameter. He had posed the question of whether it was possible for the Saturn to be so designed as to permit it to be the booster for that Air Force project.

We were shocked and stunned. This was no new problem, and we could find no reason why it should not have been considered, if necessary, during the time that the Department of Defense and NASA were debating the whole question of what kind of upper stages we should use. Nevertheless, we very speedily went about the job of estimating the project on the basis of accepting the 160-inch diameter. At the same time it was requested that we submit quotations for a complete operational program to boost the Dynasoar for a given number of flights. As usual, we were given two or three numbers, rather than one fixed quantity, and asked to estimate on each of them.

By this time, my nose was beginning to sniff a strange odor of "fish." I put my bird dogs to work to try to find out what was going on and with whom we had to compete. We discovered that the Air Force had proposed a wholly different and entirely new vehicle as the booster for Dynasoar, using a cluster of Titan engines and upgrading their performance to get the necessary first-stage thrust for take-off. This creature was variously christened the Super Titan, or the Titan C. No work had been done on this vehicle other than a hasty engineering outline. Yet the claim was made that the vehicle in a two-stage or three-stage configuration could be flown more quickly than the Saturn, on which we had already been working hard for many months. Dates and estimates were attached to that proposal which at best ignored many factors of costs, and at worst were strictly propaganda.

Developments of the Saturn IB launch vehicle were detailed in some depth in the late 1960's. There was a large payload gap between the Saturn IB's 19,000 kg low-earth orbit capacity and the two-stage Saturn V 100,000 kg capability. How to fill it was the result of an exhaustive series of Marshall and contractor trade studies.

The configurations shown were the most promising. The best solution was to add two or four UA1205 five segment solid rocket motors already developed for the Titan launch vehicle. This would boost payload to 40,000 kg. Use of seven segment motors developed for Titan 3M would bring the payload up to 48,000 kg but would require stretching the S-1B first stage by 20 feet. A more modest ten foot stretch, with Minuteman first stage motors for thrust augmentation, would bring a modest payload improvement to 23,000 kg.

In the end, no further orders for Saturns were placed. Of the 12 Saturn IB's built, only nine were flown, the remaining three becoming NASA museum pieces. If Saturn production had continued, it is likely the Saturn IB would have been discontinued anyway, and Saturn II variants would have been used for any intermediate payload requirements.

LEO Payload: 9,000 kg (19,800 lb) to a 185 km orbit at 28.00 degrees. Payload: 2,200 kg (4,800 lb) to a translunar trajectory. Development Cost $: 838.100 million. Launch Price $: 76.000 million in 1963 dollars in 1967 dollars.

Stage Data - Saturn I

- Stage 1. 1 x Saturn I. Gross Mass: 432,681 kg (953,898 lb). Empty Mass: 45,267 kg (99,796 lb). Thrust (vac): 7,582.100 kN (1,704,524 lbf). Isp: 289 sec. Burn time: 150 sec. Isp(sl): 255 sec. Diameter: 6.52 m (21.39 ft). Span: 6.52 m (21.39 ft). Length: 24.48 m (80.31 ft). Propellants: Lox/Kerosene. No Engines: 8. Engine: H-1. Status: Out of Production.

- Stage 2. 1 x Saturn IV. Gross Mass: 50,576 kg (111,500 lb). Empty Mass: 5,217 kg (11,501 lb). Thrust (vac): 400.346 kN (90,001 lbf). Isp: 410 sec. Burn time: 482 sec. Diameter: 5.49 m (18.01 ft). Span: 5.49 m (18.01 ft). Length: 12.19 m (39.99 ft). Propellants: Lox/LH2. No Engines: 6. Engine: RL-10. Status: Out of Production.

- Stage 3. 1 x Centaur C. Gross Mass: 15,600 kg (34,300 lb). Empty Mass: 1,996 kg (4,400 lb). Thrust (vac): 133.448 kN (30,000 lbf). Isp: 425 sec. Burn time: 430 sec. Diameter: 3.05 m (10.00 ft). Span: 3.05 m (10.00 ft). Length: 9.14 m (29.98 ft). Propellants: Lox/LH2. No Engines: 2. Engine: RL-10A-1. Status: Out of Production.

More at: Saturn I.

| Juno V-A American orbital launch vehicle. By 1958 the Super-Jupiter was called Juno V and the 4 E-1 engines were abandoned in favor of clustering 8 Jupiter IRBM engines below existing Redstone/Jupiter tankage. The A version had a Titan I ICBM as the upper stages. Masses, payload estimated. |

| Juno V-B American orbital launch vehicle. A proposed version of the Juno V for lunar and planetary missions used a Titan I ICBM first stage and a Centaur high-energy third stage atop the basic Juno V cluster. Masses, payload estimated. |

| Saturn A-1 American orbital launch vehicle. Projected first version of Saturn I, to be used if necessary before S-IV liquid hydrogen second stage became available. Titan 1 first stage used as second stage, Centaur third stage. Masses, payload estimated. |

| Saturn A-2 American orbital launch vehicle. More powerful version of Saturn I with low energy second stage consisting of cluster of four IRBM motors and tankage, Centaur third stage. Masses, payload estimated. |

| Saturn B-1 American orbital launch vehicle. Most powerful version of Saturn I considered. New low energy second stage with four H-1 engines, S-IV third stage, Centaur fourth stage. Masses, payload estimated. |

| Saturn C-1 American orbital launch vehicle. Original flight version with dummy upper stages, including dummy Saturn S-V/Centaur (never flown). |

| Saturn C-2 American orbital launch vehicle. The launch vehicle initially considered for realizing the Apollo lunar landing at the earliest possible date. 15 launches and rendezvous required to assemble direct landing spacecraft in earth orbit. |

| Saturn I Blk2 American orbital launch vehicle. Second Block of Saturn I, with substantially redesigned first stage and large fins to accommodate Dynasoar payload. |

| Saturn I RIFT American nuclear orbital launch vehicle. In the first half of the 1960's it was planned to make suborbital tests of nuclear propulsion for upper stages using a Saturn IB first stage to boost a Rover-reactor powered second stage on a suborbital trajectory. The second stage would impact the Atlantic Ocean down range from Cape Canaveral. |

| Saturn IB American orbital launch vehicle. Improved Saturn I, with uprated first stage and Saturn IVB second stage (common with Saturn V) replacing Saturn IV. Used for earth orbit flight tests of Apollo CSM and LM. |

| Saturn IB-A American orbital launch vehicle. Douglas Studies, 1965: S-IB with 225 k lbf H-1's; S-IVB stretched with 350,000 lbs propellants; Centaur third stage. |

| Saturn IB-B American orbital launch vehicle. Douglas Studies, 1965: S-IB with 225 k lbf H-1's; S-IVB stretched with 350,000 lbs propellants and HG-3 high performance engine. |

| Saturn IB-C American orbital launch vehicle. Douglas Studies, 1965: 4 Minuteman strap-ons; standard S-IB, S-IVB stages. |

| Saturn IB-CE American orbital launch vehicle. Douglas Studies, 1965: Standard Saturn IB with Centaur upper stage. |

| Saturn IB-D American orbital launch vehicle. Douglas Studies, 1965: Standard Saturn IB with Titan UA1205 5-segment strap-on motors. |

| Saturn INT-05 American orbital launch vehicle. NASA Study, 1965: Half length 260 inch solid motor with S-IVB upper stage. |

| Saturn INT-05A American orbital launch vehicle. UA Study, 1965: Full length 260 inch solid motor with S-IVB upper stage. |

| Saturn INT-11 American orbital launch vehicle. Chrysler Studies, 1966: S-IB with 4 Titan UA1205 with standard S-IB stage, S-IVB stage, or 4 Titan UA1207 strap-ons with 20-foot stretched S-IB stage, S-IVB stage. S-IB ignition at altitude. |

| Saturn INT-12 American orbital launch vehicle. Chrysler Studies, 1966: S-IB with only 4 H-1 motors, with 4 Titan UA1205 with standard length S-IB stage, S-IVB stage, or 4 Titan UA1207 strap-ons with 20-foot stretched S-IB stage, S-IVB stage. S-IB ignition at sea level at same time as strap-ons. |

| Saturn INT-13 American orbital launch vehicle. Chrysler Studies, 1966: S-IB with 2 Titan UA1205 with standard length S-IB stage, S-IVB stage, or 2 Titan UA1207 strap-ons with 20-foot stretched S-IB stage, S-IVB stage. S-IB ignition at sea level at same time as strap-ons. |

| Saturn INT-14 American orbital launch vehicle. Chrysler Studies, 1966: S-IB with 4 Minuteman motors as strap-ons, with no, 10, or 20-foot stretch S-IB stages, S-IVB stage. S-IB ignition at sea level at same time as strap-ons. |

| Saturn INT-15 American orbital launch vehicle. Chrysler Studies, 1966: S-IB with 8 Minuteman motors as strap-ons, with no, 10, or 20-foot stretch S-IB stages, S-IVB stage. S-IB ignition at sea level at same time as strap-ons. |

| Saturn INT-16 American orbital launch vehicle. UA Studies, 1966: S-IVB upper stage with from 2 to 5 Titan UA1205, 1206, or 1207 motors as first stage, clustered around from 1 to 3 of the same motors as a second stage. S-IVB upper stage. |

| Saturn INT-27 American orbital launch vehicle. UA study, 1965. Saturn variant using various combinations of 156 inch rocket motors as first and second stages, with S-IVB upper stage. |

| Saturn LCB-Alumizine-140 American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing Low-Cost Saturn Derivative Study, 1967 (trade study of 260 inch first stages for S-IVB, all delivering 86,000 lb payload to LEO): Low Cost Booster, Single Pressure-fed N2O4/Alumizine Propellant engine, HY-140 Steel Hull. |

| Saturn LCB-Alumizine-250 American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing Low-Cost Saturn Derivative Study, 1967 (trade study of 260 inch first stages for S-IVB, all delivering 86,000 lb payload to LEO): Low Cost Booster, Single Pressure-fed N2O4/Alumizine Propellant engine, Ni-250 Steel Hull. |

| Saturn LCB-Lox/RP-1 American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing Low-Cost Saturn Derivative Study, 1967 (trade study of 260 inch first stages for S-IVB, all delivering 86,000 lb payload to LEO): Low Cost Booster, Single Pressure-fed LOx/RFP-1 engine. |

| Saturn LCB-SR American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing Low-Cost Saturn Derivative Study, 1967 (trade study of 260 inch first stages for S-IVB, all delivering 86,000 lb payload to LEO): Low Cost Booster, 260 inch solid motor, full length. |

| Saturn LCB-Storable-250 American orbital launch vehicle. Boeing Low-Cost Saturn Derivative Study, 1967 (trade study of 260 inch first stages for S-IVB, all delivering 86,000 lb payload to LEO): Low Cost Booster, Single Pressure-fed N2O4/UDMH Propellant engine, Ni-250 Steel Hull. |

| Super-Jupiter American orbital launch vehicle. The very first design that would lead to Saturn. A 1.5 million pound thrust booster using four E-1 engines - initial consideration of using a single USAF F-1 engine abandoned because of development time. Existing missile tankage was clustered above the engines. |

| Uprated Saturn I American orbital launch vehicle. Initial version of Saturn IB with old-design Saturn IB first stage. |

Family: orbital launch vehicle. People: von Braun. Country: USA. Engines: H-1 engine, RL-10A-1, RL-10. Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing, Horizon Lunar Outpost, Mercury, Horizon Station, Ideal Home Station, Horizon LERV, Apollo LM, Apollo CSM, Apollo A, Apollo X, Highwater, Lunar Bus, MORL, Apollo D-2, Apollo L-2C, Apollo Lenticular, Surveyor, Dynasoar, Apollo CSM Block I, Jupiter nose cone, Gemini - Saturn I, Gemini - Saturn IB, Pegasus satellite, Apollo LM Lab, Apollo Experiments Pallet, Gemini Observatory, Apollo RM, Big Gemini, Apollo Rescue CSM, Skylab, Apollo ASTP Docking Module. Projects: Apollo. Launch Sites: Cape Canaveral, Cape Canaveral LC34, Cape Canaveral LC37B. Stages: Saturn IV, Centaur C, S-I stage. Bibliography: 16, 17, 18, 2, 216, 22, 222, 228, 231, 232, 234, 26, 27, 279, 33, 376, 45, 452, 47, 6, 60, 86.

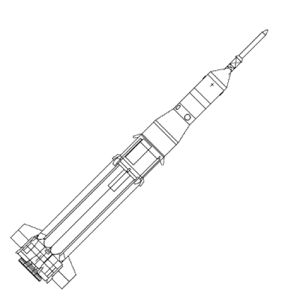

| Saturn 1 Credit: © Mark Wade |

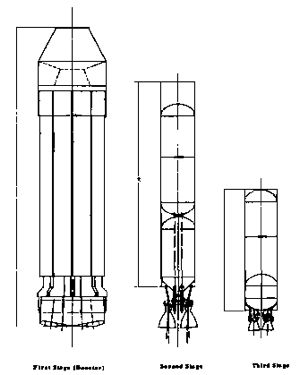

| Saturn I (1959) Saturn I configuration for Project Horizon Credit: US Army |

| Saturn I Stages Saturn I , stages 1 to 3, configuration for Project Horizon (1959) Credit: US Army |

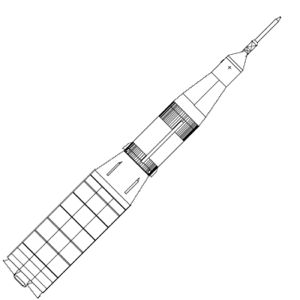

| Saturn I As conceived for Project Horizon, 1958. Credit: © Mark Wade |

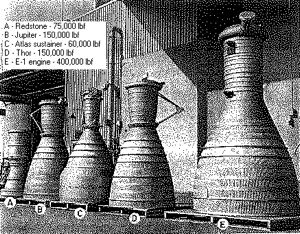

| E-1 Engine Credit: © Mark Wade |

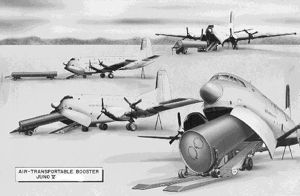

| Juno-5 Airlift The Juno-5 was designed to be air-transportable and assembled at austere launch pads. |

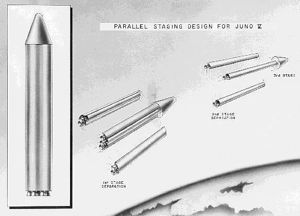

| Juno-5 Parallel Stag A parallel staging scheme was considered for the Juno-5. This would have resulted in a vehicle similar to the Russian R-7 launcher. |

| Juno-5 Recovery Full recovery and reuse of the Juno-5 was planned. The structural provisions were retained in the earliest Saturn I test vehicles, but never used. |

| Juno-5 on Test Stand The very first Juno-5 test article firing on the stand at the Redstone Arsenal. |

| Saturn A-1 to C-5 Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn 1B Credit: © Mark Wade |

| J-2 Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn 1B LC34 Credit: NASA |

| Saturn 1B LC39 Credit: NASA |

| Saturn 1B with LM Saturn 1B with LM Payload Credit: NASA |

| Saturn 1B rad Credit: NASA |

| Saturn IB-INT-5B Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn 1B/4 SRBs Saturn 1B with 4 solids replacing S-1B Credit: © Mark Wade |

| Saturn 1B/MM SRB Saturn 1B with Minuteman strapons Credit: © Mark Wade |

1957 April - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Studies of a large clustered-engine booster - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The U.S. Army Ballistic Missile Agency, Redstone Arsenal, Ala., began studies of a large clustered-engine booster to generate 1.5 million pounds of thrust, as one of a related group of space vehicles. During 1957-1958, approximately 50,000 man-hours were expended in this effort.

1957 July 29 - . LV Family: Titan, Saturn I, .

- Follow-on ballistic missiles and space programs - .

AFBMD presented the Air Force Scientific Advisory Board's Ad Hoc Committee with a summary of follow-on ballistic missile weapon systems and advanced space programs that could be undertaken. Included among the programs was the proposed development of high-thrust space vehicles for orbital and lunar flights.

1957 December 10 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- National Integrated Missile and Space Vehicle Development Program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Horizon.

The Army Ballistic Missile Agency completed and forwarded to higher authority the first edition of A National Integrated Missile and Space Vehicle Development Program, which had been in preparation since April 1957. Included was a "short-cut development program" for large payload capabilities, covering the clustered-engine booster of 1.5 million pounds of thrust to be operational in 1963. The total development cost of $850 million during the years 1958-1963 covered 30 research and development flights, some carrying manned and unmanned space payloads. One of six conclusions given in the document was that "Development of the large (1520 K-pounds thrust) booster is considered the key to space exploration and warfare." Later vehicles with greater thrust were also described.

1957 December 30 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I first proposed. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Von Braun produces 'Proposal for a National Integrated Missile and Space Vehicle Development Plan'. First mention of 1,500,000 lbf booster (Saturn I).

1958 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Juno V-A.

- Juno V heavy space launch design - . Nation: USA. The Von Braun team's Super-Jupiter evolved into the Juno V. The 4 E-1 engines were abandoned in favor of clustering 8 Jupiter IRBM engines below existing Redstone/Jupiter tankage..

1958 July 29 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I initial contract. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. ARPA gives Von Braun team contract to develop Saturn I (called 'cluster's last stand' due to design concept)..

1958 August 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I project initiated by ARPA. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The Advanced Research Projects Agency ARPA provided the Army Ordnance Missile Command (AOMC) with authority and initial funding to develop the Juno V (later named Saturn launch vehicle. ARPA Order 14 described the project: "Initiate a development program to provide a large space vehicle booster of approximately 1.5 million pounds of thrust based on a cluster of available rocket engines. The immediate goal of this program is to demonstrate a full-scale captive dynamic firing by the end of calendar year 1959." Within AOMC, the Juno V project was assigned to the Army Ballistic Missile Agency at Redstone Arsenal Huntsville, Ala.

1958 September 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Redstone Arsenal begins Saturn I design studies. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Saturn design studies authorized to proceed at Redstone Arsenal for development of 1.5-million-pound-thrust cluster first stage..

1958 September 11 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Letter contract for the development of the Saturn H-1 rocket engine - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. A letter contract was signed by NASA with NAA's Rocketdyne Division for the development of the H-1 rocket engine, designed for use in a clustered-engine booster..

1958 September 23 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Juno V project objective changed to multistage carrier vehicle - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Johnson, Roy,

Medaris,

von Braun.

Program: Horizon.

Following a Memorandum of Agreement between Maj. Gen. John B. Medaris of Army Ordnance Missile Command (AOMC) and Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) Director Roy W. Johnson on this date and a meeting on November 4, ARPA and AOMC representatives agreed to extend the Juno V project. The objective of ARPA Order 14 was changed from booster feasibility demonstration to "the development of a reliable high performance booster to serve as the first stage of a multistage carrier vehicle capable of performing advanced missions."

1958 October 11 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Contract for development of the H-1 engine - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Pioneer I, intended as a lunar probe, was launched by a Thor-Able rocket from the Atlantic Missile Range, with the Air Force acting as executive agent to NASA. The 39-pound instrumented payload did not reach escape velocity..

1958 December 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- ABMA Briefing to NASA - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Class: Manned. Type: Manned space station. Von Braun briefs NASA on plans for booster development at Huntsville with objective of manned lunar landing. Initally proposed using 15 Juno V (Saturn I) boosters to assemble 200,000 kg payload in earth orbit for direct landing on moon..

1958 December 17 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn H-1 engine first full-power firing - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The H-1 engine successfully completed its first full-power firing at NAA's Rocketdyne facility in Canoga Park, Calif..

1958 December 17 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Military and NASA consider future launch vehicles - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Representatives of Advanced Research Projects Agency, the military services, and NASA met to consider the development of future launch vehicle systems. Agreement was reached on the principle of developing a small number of versatile launch vehicle systems of different thrust capabilities, the reliability of which could be expected to be improved through use by both the military services and NASA.

1959 January 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- NASA Large Booster Review Committee - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The Army Ordnance Missile Command (AOMC), the Air Force, and missile contractors presented to the ARPA-NASA Large Booster Review Committee their views on the quickest and surest way for the United States to attain large booster capability. The Committee decided that the Juno V approach advocated by AOMC was best and NASA started plans to utilize the Juno V booster.

1959 February 2 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Booster name changed from Juno V to Saturn - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: Johnson, Roy, von Braun. Program: Apollo. The Army proposed that the name of the large clustered-engine booster be changed from Juno V to Saturn, since Saturn was the next planet after Jupiter. Roy W. Johnson, Director of the Advanced Research Projects Agency, approved the name on February 3..

1959 February 4 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Early agreement required on Saturn upper stages - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Johnson, Roy,

Medaris,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Maj. Gen. John B. Medaris of the Army Ordnance Missile Command (AOMC) and Roy W. Johnson of the Advanced Research Projects Agency (ARPA) discussed the urgency of early agreement between ARPA and NASA on the configuration of the Saturn upper stages. Several discussions between ARPA and NASA had been held on this subject. Johnson expected to reach agreement with NASA the following week. He agreed that AOMC would participate in the overall upper stage planning to ensure compatibility of the booster and upper stages.

1959 April 15 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn A-1.

- Use of Titan for Saturn upper stages - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

In response to a request by the DOD-NASA) Saturn Ad Hoc Committee, the Army Ordnance Missile Command (AOMC) sent a supplement to the "Saturn System Study" to the Advanced Research Projects Agency ARPA describing the use of Titan for Saturn upper stages. Additional Details: here....

1959 May 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Unmanned Lunar Soft Landing Vehicle - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Spacecraft: Surveyor. The Army Ordnance Missile Command submitted to NASA a report entitled "Preliminary Study of an Unmanned Lunar Soft Landing Vehicle," recommending the use of the Saturn booster..

1959 May 3 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- First H-1 engine for the Saturn delivered - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The first Rocketdyne H-1 engine for the Saturn arrived at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA ). The H-1 engine was installed in the ABMA test stand on May 7, first test-fired on May 21, and fired for 80 seconds on May 29. The first long-duration firing - 151.03 seconds - was on June 2.

1959 May 25-26 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- National booster program, Dyna-Soar, and Mercury discussed - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Faget,

Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Mercury.

The national booster program, Dyna-Soar, and Project Mercury were discussed by the Research Steering Committee. Members also presented reviews of Center programs related to manned space flight. Maxime A. Faget of STG endorsed lunar exploration as the present goal of the Committee although recognizing the end objective as manned interplanetary travel. George M. Low of NASA Headquarters recommended that the Committee:

- Adopt the lunar landing mission as its long-range objective.

- Investigate vehicle staging so that Saturn could be used for manned lunar landings without complete reliance on Nova.

- Make a study of whether parachute or airport landing techniques should be emphasized.

- Consider nuclear rocket propulsion possibilities for space flight.

- Attach importance to research on auxiliary power plants such as hydrogen-oxygen systems.

1959 May 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- First H-1 engine for Saturn I fired. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. ABMA static fired a single H-1 Saturn engine at Redstone Arsenal, Ala..

1959 June 3 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Construction begins of the first Saturn launch complex - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Construction of the first Saturn launch area, Complex 34, began at Cape Canaveral, FIa..

1959 June 5 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

1959 June 18 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- NASA funded study of a lunar exploration program based on Saturn - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA authorized $150,000 for Army Ordnance Missile Command studies of a lunar exploration program based on Saturn-boosted systems. To be included were circumlunar vehicles, unmanned and manned; close lunar orbiters; hard lunar impacts; and soft lunar landings with stationary or roving payloads.

1959 June 25-26 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Lunar mission studies under way at the Army - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Horizon. Spacecraft: Mercury. During the Research Steering Committee meeting, John H. Disher of NASA Headquarters discussed the lunar mission studies under way at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency (ABMA).. Additional Details: here....

1959 October 21 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Transfer to NASA of the Army Ballistic Missile Agency's Development Operations Division - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Eisenhower,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

After a meeting with officials concerned with the missile and space program, President Dwight D. Eisenhower announced that he intended to transfer to NASA control the Army Ballistic Missile Agency's Development Operations Division personnel and facilities. The transfer, subject to congressional approval, would include the Saturn development program.

1959 November 2 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Transfer of Saturn I project to NASA announced. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: Eisenhower, von Braun. Program: Apollo. President Eisenhower announced his intention of transferring the Saturn project to NASA, which became effective on March 15, 1960..

1959 December 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Plan for transferring the Army Ballistic Missile Agency and Saturn to NASA - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Eisenhower,

Glennan,

von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The initial plan for transferring the Army Ballistic Missile Agency and Saturn to NASA was drafted. It was submitted to President Dwight D. Eisenhower on December 1 1 and was signed by Secretary of the Army Wilber M. Brucker and Secretary of the Air Force James H. Douglas on December 16 and by NASA Administrator T. Keith Glennan on December 17.

1959 December 7 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Engineering and cost study for a new Saturn configuration - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The Advanced Research Projects Agency ARPA and NASA requested the Army Ordnance Missile Command AOMC to prepare an engineering and cost study for a new Saturn configuration with a second stage of four 20,000-pound-thrust liquid-hydrogen and liquid-oxygen engines (later called the S-IV stage) and a modified Centaur third stage using two of these engines later designated the S-V stage). Additional Details: here....

1959 December 8-9 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Army Ballistic Missile Agency mission possibilities - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

H. H. Koelle told members of the Research Steering Committee of mission possibilities being considered at the Army Ballistic Missile Agency. These included an engineering satellite, an orbital return capsule, a space crew training vehicle, a manned orbital laboratory, a manned circumlunar vehicle, and a manned lunar landing and return vehicle. He described the current Saturn configurations, including the "C" launch vehicle to be operational in 1967. The Saturn C (larger than the C-1) would be able to boost 85,000 pounds into earth orbit and 25,000 pounds into an escape trajectory.

1959 December 9 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Goett Committee - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Class: Manned. Type: Manned space station. Committee formed to recommend post-Mercury space program. After four meetings, and studying earth-orbit assembly using Saturn II or direct ascent using Nova, tended to back development of Nova..

1959 December 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn upper stage study. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. NASA team completed study design of upper stages of Saturn launch vehicle..

1960 February 1 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Lunar Exploration Program Based Upon Saturn Systems - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The Army Ballistic Missile Agency submitted to NASA the study entitled "A Lunar Exploration Program Based Upon Saturn-Boosted Systems." In addition to the subjects specified in the preliminary report of October 1, 1959, it included manned lunar landings.

1960 February 29 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Eleven companies submitted contract proposals for the Saturn second stage - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Eleven companies submitted contract proposals for the Saturn second stage (S-IV): Bell Aircraft Corporation; The Boeing Airplane Company; Chrysler Corporation; General Dynamics Corporation, Convair Astronautics Division; Douglas Aircraft Company, Inc.; Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation; Lockheed Aircraft Corporation; The Martin Company; McDonnell Aircraft Corporation; North American Aviation, Inc.; and United Aircraft Corporation.

1960 March 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I transferred to NASA. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The Army Ballistic Missile Agency's Development Operations Division and the Saturn program were transferred to NASA after the expiration of the 60-day limit for congressional action on the President's proposal of January 14. (The President's decision had been made on October 21, 1959.) By Executive Order, the President named the facilities the "George C. Marshall Space Flight Center." Formal transfer took place on July 1.

1960 March 28 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Two H-1's fired together. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Two of Saturn's first-stage engines passed initial static firing test of 7.83 seconds duration at Huntsville, Ala..

1960 April 1-May 3 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Guidelines for an advanced manned spacecraft program presented by STG - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM ECS,

CSM Source Selection.

Members of STG presented guidelines for an advanced manned spacecraft program to NASA Centers to enlist research assistance in formulating spacecraft and mission design.

To open these discussions, Director Robert R. Gilruth summarized the guidelines: manned lunar reconnaissance with a lunar mission module, corollary earth orbital missions with a lunar mission module and with a space laboratory, compatibility with the Saturn C-1 or C-2 boosters (weight not to exceed 15,000 pounds for a complete lunar spacecraft and 25,000 pounds for an earth orbiting spacecraft), 14-day flight time, safe recovery from aborts, ground and water landing and avoidance of local hazards, point (ten square-mile) landing, 72-hour postlanding survival period, auxiliary propulsion for maneuvering in space, a "shirtsleeve" environment, a three-man crew, radiation protection, primary command of mission on board, and expanded communications and tracking facilities. In addition, a tentative time schedule was included, projecting multiman earth orbit qualification flights beginning near the end of the first quarter of calendar year 1966.

1960 April 1-May 3 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Guidelines for the advanced manned spacecraft program - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

STG's Robert O. Piland, during briefings at NASA Centers, presented a detailed description of the guidelines for missions, propulsion, and flight time in the advanced manned spacecraft program:

- The spacecraft should be capable ultimately of manned circumlunar reconnaissance. As a logical intermediate step toward future goals of lunar and planetary landing many of the problems associated with manned circumlunar flight would need to be solved.

- The lunar spacecraft should be capable of earth orbit missions for initial evaluation and training. The reentry component of this spacecraft should be capable of missions in conjunction with space laboratories or space stations. To accomplish lunar reconnaissance before a manned landing, it would be desirable to approach the moon closer than several thousand miles. Fifty miles appeared to be a reasonable first target for study purposes.

- The spacecraft should be designed to be compatible with the Saturn C-1 or C-2 boosters for the lunar mission. The multiman advanced spacecraft should not weigh more than 15,000 pounds including auxiliary propulsion and attaching structure.

- A flight-time capability of the spacecraft for 14 days without resupply should be possible. Considerable study of storage batteries, fuel cells, auxiliary power units, and solar batteries would be necessary. Items considered included the percentage of the power units to be placed in the "caboose" (space laboratory), preference for the use of storage batteries for both power and radiation shielding, and redundancy for reliability by using two different types of systems versus two of the same system.

1960 April 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Four H-1's fired together. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Four of the eight H-1 engines of the Saturn C-1 first-stage booster were successfully static-fired at Redstone Arsenal for seven seconds..

1960 April 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Douglas to build the second stage (S-IV) of the Saturn C-1 - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. NASA announced the selection of the Douglas Aircraft Company to build the second stage (S-IV) of the Saturn C-1 launch vehicle..

1960 April 29 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- All eight H-1 engines of the Saturn C-1 first stage ground-tested simultaneously - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. At Redstone Arsenal, all eight H-1 engines of the first stage of the Saturn C-1 launch vehicle were static-fired simultaneously for the first time and achieved 1.3 million pounds of thrust..

1960 May 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- First public demonstration of the H-1 engine - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Eight H-1 engines of the first stage of the Saturn C-1 launch vehicle were static-fired for 35.16 seconds, producing 1.3 million pounds of thrust. This first public demonstration of the H-1 took place at Marshall Space Flight Center..

1960 May 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Assembly of the first Saturn flight booster began - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Assembly of the first Saturn flight booster, SA-1, began at Marshall Space Flight Center..

1960 June 8 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Full Saturn I engine cluster full duration test. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Complete eight-engine static firing of Saturn successfully conducted for 110 seconds at MSFC, the longest firing to date..

1960 June 15 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn C-1 first stage completed test series - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. The Saturn C-1 first stage successfully completed its first series of static tests at the Marshall Space Flight Center with a 122-second firing of all eight H-1 engines..

1960 July 14-15 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Space Exploration Program Council - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The third meeting of the Space Exploration Program Council was held at NASA Headquarters. The question of a speedup of Saturn C-2 production and the possibility of using nuclear upper stages with the Saturn booster were discussed. The Office of Launch Vehicle Programs would plan a study on the merits of using nuclear propulsion for some of NASA's more sophisticated missions. If the study substantiated such a need, the amount of in-house basic research could then be determined.

1960 September 13 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Apollo Study Bidder's Conference - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Class: Moon. Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, Apollo Lunar Landing, CSM ECS, CSM Source Selection. Bidder's conference for circumlunar Apollo. Specification: Saturn C-2 compatability (6,800 kg mass for circumlunar mission); 14 day flight time; three-man crew in shirt-sleeve environment..

1960 September 30 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Space Exploration Program Council - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Low, George.

Program: Apollo.

The fourth meeting of the Space Exploration Program Council was held at NASA Headquarters. The results of a study on Saturn development and utilization was presented by the Ad Hoc Saturn Study Committee. Objectives of the study were to determine (1) if and when the Saturn C-2 launch vehicle should be developed and (2) if mission and spacecraft planning was consistent with the Saturn vehicle development schedule. No change in the NASA Fiscal Year 1962 budget was contemplated. The Committee recommended that the Saturn C-2 development should proceed on schedule (S-II stage contract in Fiscal Year 1962, first flight in 1965). The C-2 would be essential, the study reported, for Apollo manned circumlunar missions, lunar unmanned exploration, Mars and Venus orbiters and capsule landers, probes to other planets and out-of- ecliptic, and for orbital starting of nuclear upper stages. Additional Details: here....

1960 December 2 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I static firing. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. First of new series of static firings of Saturn considered only 50 percent successful in 2-second test at MSFC..

1960 December 13 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn transport barge commissioned. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Palaemon, a 180-foot barge built to transport the Saturn launch vehicle from MSFC to Cape Canaveral by water, was formally accepted by MSFC Director from Maj. Gen. Frank S. Besson, Chief of Army Transportation..

1961 January 9 - . LV Family: Atlas, Saturn I, Titan. Launch Vehicle: Titan 3.

- USAF need for a space launch vehicle with 15,000 lb payload - . Headquarters USAF instructed AFBMD to continue its efforts to define the need for a space launch vehicle with a payload capacity between the Atlas/Centaur (9,000 lbs) and the early Saturn (19,000 lbs).

1961 January 26 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn C-1 changed to a two-stage configuration - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Wernher von Braun, Director of Marshall Space Flight Center, proposed that the Saturn C-1 launch vehicle be changed from a three-stage to a two-stage configuration to meet Apollo program schedules. The planned third stage (S-V) would be dropped..

1961 January - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn first stage recovery system study - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Marshall Space Flight Center awarded contracts to NAA and Ryan Aeronautical Corporation to investigate the feasibility of recovering the first stage (S-I) of the Saturn launch vehicle by using a Rogallo wing paraglider..

1961 February 7 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Final report of the Low Committee - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Seamans.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing.

The Manned Lunar Landing Task Group (Low Committee) transmitted its final report to NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr. The Group found that the manned lunar landing mission could be accomplished during the decade, using either the earth orbit rendezvous or direct ascent technique. Multiple launchings of Saturn C-2 launch vehicles would be necessary in the earth orbital mode, while the direct ascent technique would require the development of a Nova-class vehicle. Information to be obtained through supporting unmanned lunar exploration programs, such as Ranger and Surveyor, was felt to be essential in carrying out the manned lunar mission. Total funding for the program was estimated at just under $7 billion through Fiscal Year 1968.

1961 March 1 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Current Saturn launch vehicle configurations announced - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

The current Saturn launch vehicle configurations were announced:

- C-1:

- S-I stage eight H-1 engines, 1.5 million pounds of thrust; S-IV stage four (LR-119 engines, 70,000 pounds of thrust); and S-V stage (two LR-119 engines, 35,000 pounds of thrust).

- C-2 (four-stage version):

- S-1 stage (same as first stage of the C-1); S-II (not determined); S-IV (same as second stage of the C-1); S-V (same as third Stage of C- 1).

- C-2 (three-stage version):

- S-I (same as first stage of C-1); S-II (not determined); and S-IV (same as third stage of C-1).

1961 March 7 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- First flight Saturn I on test stand. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. First flight model of Saturn booster (SA-1) installed on static test stand for preflight checkout, Marshall Space Flight Center, Huntsville..

1961 March 23 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Configuration changes for the Saturn C-1 launch vehicles - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Representatives of Marshall Space Flight Center recommended configuration changes for the Saturn C-1 launch vehicles to NASA Headquarters. These included:

- Elimination of third-stage development, since two stages could put more than ten tons into earth orbit.

- Use of six LR-115 (15,000-pound) Centaur engines (second-stage thrust thus increased from 70,000 to 90,000 pounds).

- Redesign of the first stage (S-1) to offer more safety for manned missions.

1961 March 30 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I RIFT.

- RIFT flight briefed to contractors. - . Nation: USA. Program: NERVA. Reactor-in-flight-test system (Rift) study, a part of the NASA-AEC program on nuclear rockets, was briefed by contractors at NASA headquarters..

1961 April 28 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Dynasoar launch by Saturn I studied. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Class: Manned. Type: Manned spaceplane. Spacecraft: Dynasoar. Final NASA report on the study proposed for Saturn for use as Dyna-Soar booster was presented to the Air Force..

1961 April 29 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I fight qualification. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The first successful flight qualification test of the Saturn SA-1 booster took place in an eight-engine test lasting 30 seconds..

1961 April - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Air transport of the Saturn C-1 second stage feasible - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. The Douglas Aircraft Company reported that air transport of the Saturn C-1 second stage (S-IV) was feasible..

1961 May 2 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Ad Hoc Task Group for a Manned Lunar Landing Study - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA Associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr., established the Ad Hoc Task Group for a Manned Lunar Landing Study, to be chaired by William A. Fleming of NASA Headquarters. The study was expected to produce the following information:

- All tasks associated with the mission.

- Interdependent time-phasing of the tasks.

- Areas requiring considerable technological advancements from the current state of the art.

- Tasks for which multiple approach solutions were advisable.

- Important action and decision points in the mission plan.

- A refined estimate by task and by fiscal year of the dollar resources required for the mission.

- Refined estimates of in-house manpower requirements, by task and by fiscal year

- Tentative in-house and contractor task assignments accompanying the dollar and manpower resource requirements.

- The manned lunar landing target date was 1967.

- Intermediate missions of multiman orbital satellites and manned circumlunar missions were desirable at the earliest possible time.

- Man's mission on the moon as it affected the study was to be determined by the Ad Hoc Task Group - i.e., the time to be spent on the lunar surface and the tasks to be performed while there.

- In establishing the mission plan, the use of the Saturn C-2 launch vehicle was to be evaluated as compared with an alternative launch vehicle having a higher thrust first stage and C-2 upper-stage components.

- The mission plan was to include parallel development of liquid and solid propulsion leading to a Nova vehicle 400,000 pounds in earth orbit and should indicate when the decision should be made on the final Nova configuration.

- Nuclear-powered launch vehicles should not be considered for use in the first manned lunar landing mission.

- The flight test program should be laid out with enough launchings to meet the needs of the program considering the reliability requirements.

- Alternative approaches should be provided in critical areas - e.g., upper stages and mission modes.

The engineering sketch drawn by John D. Bird of Langley Research Center on May 3, 1961, indicated the thinking of that period: By launching two Saturn C-2's, the lunar landing mission could be accomplished by using both earth rendezvous and lunar rendezvous at various stages of the mission.

1961 May 8 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- S-IV satisfactory for Apollo missions - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

After study and discussion by STG and Marshal! Space Flight Center officials, STG concluded that the current 154-inch diameter of the second stage (S-IV) adapter for the Apollo spacecraft would be satisfactory for the Apollo missions on Saturn flights SA-7, SA-8, SA-9, and SA-10.

1961 June 1 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Change in the Saturn C-1 configuration - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

NASA announced a change in the Saturn C-1 vehicle configuration. The first ten research and development flights would have two stages, instead of three, because of the changed second stage (S-IV) and, starting with the seventh flight vehicle, increased propellant capacity in the first stage (S-1) booster.

1961 June 2 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I transport route interdicted. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. Collapse of a lock in the Wheeler Dam below Huntsville on the Tennessee River interdicted the planned water route of the first Saturn space booster from Marshall Space Flight Center to Cape Canaveral on the barge Palaemon..

1961 June 5 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC34. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I launch complex completed. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Huge Saturn launch complex at Cape Canaveral dedicated in brief ceremony by NASA, construction of which was supervised by the Army Corps of Engineers. Giant gantry, weighing 2,800 tons and being 310 feet high, is largest movable land structure in North America.

1961 June 10 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Lundin Committee recommended earth orbit rendezvous mode - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Seamans.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing.

'The Lundin Committee completed its study of various vehicle systems for the manned lunar landing mission, as requested on May 25 by NASA associate Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr. The Committee had considered alternative methods of rendezvous: earth orbit, lunar orbit, a combination of earth and lunar orbit, and lunar surface. Launch vehicles studied were the Saturn C-2 and C-3. Conclusion was that 43,000 kg stage (85% fuel) was needed for a lunar landing mission. The concept of a low- altitude earth orbit rendezvous using two or three C-3's was clearly preferred by the Committee. Reasons for this preference were the small number of launches and orbital operations required and the fact that the Saturn C- 3 was considered to be an efficient launch vehicle of great utility and future growth.

1961 June 22 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- First decision on Apollo launch vehicles - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Webb.

Program: Apollo.

Class: Manned.

Type: Manned space station. Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing.

Meeting with Webb/Dryden, work on Saturn C-2 stopped; preliminary design of C-3 and continuing studies of larger vehicles for landing missions requested. STG push for 4 x 6.6 m diameter solid cluster first stage rejected for safety and ground handling reasons.

1961 June 23 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn C-1 to be operational in 1964 - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. NASA announced that the Saturn C-1 launch vehicle, which could place ten-ton payloads in earth orbit, would be operational in 1964..

1961 June 23 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Saturn C-2 discontinued - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing.

NASA announced that further engineering design work on the Saturn C-2 configuration would be discontinued and that effort instead would be redirected toward clarification of the Saturn C-3 and Nova concepts. Investigations were specifically directed toward determining capabilities of the proposed C-3 configuration in supporting the Apollo mission.

1961 June 26 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn I barge replacement. - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. A Navy YFNB barge was obtained by NASA to serve as a replacement for the Palaemon in transporting of the Saturn booster to Cape Canaveral..

1961 July 24 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-2.

- Changes in Saturn launch vehicle configurations - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

Changes in Saturn launch vehicle configurations were announced :

- C-1:

- Stages S-I (1.5 million pounds of thrust) and S-IV

- C-2:

- Stages S-I, S-II, and S-IV

- C-3:

- Stages S-IB (3 million pounds of thrust), S-II, and S-IV.

1961 July 28 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- NASA invitation to bids for Apollo prime contract - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM Original Specification,

CSM Source Selection.

NASA invited 12 companies to submit prime contractor proposals for the Apollo spacecraft by October 9: The Boeing Airplane Company, Chance Vought Corporation, Douglas Aircraft Company, General Dynamics/Convair, the General Electric Company, Goodyear Aircraft Corporation, Grumman Aircraft Engineering Corporation, Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, McDonnell Aircraft Corporation, The Martin Company, North American Aviation, Inc., and Republic Aviation Corporation. Additional Details: here....

1961 Aug - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn.

- The NASA-DoD Large Launch Vehicle Planning Group. - . The NASA-DoD Large Launch Vehicle Planning Group met to study policy management and requirements for launch vehicles up to the size of Saturn..

1961 August 5 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- First Saturn I leaves factory. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. First Saturn (SA-1) booster began water trip to Cape Canaveral on Navy barge Compromise after overland detour around Wheeler Dam..

1961 August 14 - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- First Saturn I arrives at Cape Canaveral. - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. Navy barge Compromise, carrying first Saturn booster, stuck in the mud in the Indian River just south of Cape Canaveral. Released several hours later, the Saturn was delayed only 24 hours in its 2,200-mile journey from Huntsville..

1961 October 27 - . 15:06 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC34. LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-1.

- Nation: USA.

Agency: NASA.

Apogee: 136 km (84 mi).

Largest known rocket launch to date, the Saturn I 1st stage booster, successful on first test flight from Atlantic Missile Range. With its eight clustered engines developing almost 1.3 million pounds of thrust at launch, the Saturn (SA-1) hurled waterfilled dummy upper stages to an altitude of 84.8 miles and 214.7 miles down range. In a postlaunch statement, Administrator Webb said: "The flight today was a splendid demonstration of the strength of our national space program and an important milestone in the buildup of our national capacity to launch heavy payloads necessary to carry out the program projected by President Kennedy on May 25.".

1961 November 17 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Contract issued for build of 20 Saturn I's. - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: von Braun.

Program: Apollo.

NASA announced that the Chrysler Corporation had been chosen to build 20 Saturn first-stage (S-1) boosters similar to the one tested successfully on October 27 . They would be constructed at the Michoud facility near New Orleans, La. The contract, worth about $200 million, would run through 1966, with delivery of the first booster scheduled for early 1964.

1961 December 7 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I RIFT.

- Kiwi B-1A tests completed. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: NERVA.

Power run completed the test series on the Kiwi B-1A reactor system being conducted at the Nevada Test Site by AEC's Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory. Fourth in a series of test reactors in the joint AEC-NASA nuclear rocket propulsion program, Kiwi B-1A was disassembled for examination at the conclusion of the test runs.

1961 December 8 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Support service contractor selected for Michoud. - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

NASA selected Mason-Rust as the contractor to provide support services at NASA's Michoud plant near New Orleans, providing housekeeping services through June 30, 1962 for the three contractors who would produce the Saturn S-I and S-IB boosters and the Rift nuclear upper-stage vehicle.

1962 April 25 - . 14:00 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC34. LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-1.

- Nation: USA.

Agency: NASA.

Apogee: 145 km (90 mi).

Second suborbital test of Saturn I. The Saturn SA-2 first stage booster was launched successfully from Cape Canaveral. The rocket was blown up intentionally and on schedule about 2.5 minutes after liftoff at an altitude of 65 miles, dumping the water ballast from the dummy second and third stages into the upper atmosphere. The experiment, Project Highwater, produced a massive ice cloud and lightning-like effects. The eight clustered H-1 engines in the first stage produced 1.3 million pounds of thrust and the maximum speed attained by the booster was 3,750 miles per hour. Modifications to decrease the slight fuel sloshing encountered near the end of the previous flight test were successful.

1962 August 16 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- S-IV successfully static-fired for the first time - . Nation: USA. Related Persons: von Braun. Program: Apollo. The second stage (S-IV) of the Saturn C-1 launch vehicle was successfully static-fired for the first time in a ten-second test at the Sacramento, Calif., facility by the Douglas Aircraft Company..

1962 November 16 - . 17:45 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC34. LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn C-1.

- Nation: USA.

Agency: NASA.

Apogee: 167 km (103 mi).

Third suborbital test of Saturn I. Saturn-Apollo 3 (Saturn C-1, later called Saturn I) was launched from the Atlantic Missile Range. Upper stages of the launch vehicle were filled with 23000 gallons of water to simulate the weight of live stages. At its peak altitude of 167 kilometers (104 miles), four minutes 53 seconds after launch, the rocket was detonated by explosives upon command from earth. The water was released into the ionosphere, forming a massive cloud of ice particles several miles in diameter. By this experiment, known as "Project Highwater," scientists had hoped to obtain data on atmospheric physics, but poor telemetry made the results questionable. The flight was the third straight success for the Saturn C-1 and the first with maximum fuel on board.

1963 January 10 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Unmanned Apollo spacecraft to be flown on Saturn C-1 - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. MSC and OMSF agreed that an unmanned Apollo spacecraft must be flown on the Saturn C-1 before a manned flight. SA-10 was scheduled to be the unmanned flight and SA-111, the first manned mission..

1963 February 20 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn engine-out capability investigated - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

At a meeting of the MSC-MSFC Flight Mechanics Panel, it was agreed that Marshall would investigate "engine-out" capability (i.e., the vehicle's performance should one of its engines fail) for use in abort studies or alternative missions. Not all Saturn I, IB, and V missions included this engine-out capability. Also, the panel decided that the launch escape system would be jettisoned ten seconds after S-IV ignition on Saturn I launch vehicles.

1963 March 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- North American completed Apollo boilerplate (BP) 9 - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo CSM,

CSM LES.

North American completed construction of Apollo boilerplate (BP) 9, consisting of launch escape tower and CSM. It was delivered to MSC on March 18, where dynamic testing on the vehicle began two days later. On April 8, BP-9 was sent to MSFC for compatibility tests with the Saturn I launch vehicle.

1963 March 13 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- First long-duration static test of Saturn SA-5 first stage - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

The first stage of the Saturn SA-5 launch vehicle was static fired at MSFC for 144.44 seconds in the first long-duration test for a Block II S-1. The cluster of eight H-1 engines produced 680 thousand kilograms (1.5 million pounds) of thrust. An analysis disclosed anomalies in the propulsion system. In a final qualification test two weeks later, when the engines were fired for 143.47 seconds, the propulsion problems had been corrected.

1963 March 28 - . 20:11 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC34. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Nation: USA.

Agency: NASA.

Apogee: 129 km (80 mi).

Fourth suborbital test of Saturn I. The S-I Saturn stage reached an altitude of 129 kilometers (80 statute miles) and a peak velocity of 5,906 kilometers (3,660 miles) per hour. This was the last of four successful tests for the first stage of the Saturn I vehicle. After 100 seconds of flight, No. 5 of the booster's eight engines was cut off by a preset timer. That engine's propellants were rerouted to the remaining seven, which continued to burn. This experiment confirmed the "engine-out" capability that MSFC engineers had designed into the Saturn I.

1963 April 17 - . LV Family: Saturn V, Saturn I, Titan.

- Large Solid Rocket Motor Program (Program 623A) begun. - .

The Defense Department announced the selection of Thiokol Chemical Corporation, Aerojet-General Corporation, and Lockheed Propulsion Company to conduct work on the development of large solid-propellant motors as part of the Space Systems Division's Large Solid Rocket Motor Program (Program 623A). Development work was divided into four tasks: (1) Thiokol and Aerojet-General were to develop 260-inch diameter, solid rocket motors of 3 million pounds of thrust for demonstration static firings; (2) Thiokol was to work on a 156-inch, 3 million-pound thrust, two-segment solid rocket motor; (3) Thiokol was to develop and static fire a 156-inch, one-segment solid rocket motor of one million pounds thrust demonstrating thrust vector control (TVC) through movable nozzles; and (4) Lockheed was to static fire a 156-inch, single segment solid rocket motor of one million pounds thrust that demonstrated TVC through jet tabs.

1963 August 5 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- First static firing test of Saturn S-IV stage for SA-5 - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

In what was to have been an acceptance test, the Douglas Aircraft Company static fired the first Saturn S-IV flight stage at Sacramento, Calif. An indication of fire in the engine area forced technicians to shut down the stage after little more than one minute's firing. A week later the acceptance test was repeated, this time without incident, when the vehicle was fired for over seven minutes. (The stage became part of the SA-5 launch vehicle, the first complete Saturn I to fly.)

1963 September 16 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Apollo launch escape system modified - . Nation: USA. Program: Apollo. The launch escape system was modified so that, under normal flight conditions, the crew could jettison the tower. On unmanned Saturn I flights, tower jettison was initiated by a signal from the instrument unit of the S-IV (second) stage..

1963 September 26 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn IB.

- Apollo mission plans - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo LM.

OMSF, MSC, and Bellcomm representatives, meeting in Washington, D.C., discussed Apollo mission plans: OMSF introduced a requirement that the first manned flight in the Saturn IB program include a LEM. ASPO had planned this flight as a CSM maximum duration mission only.

- Bellcomm was asked to develop an Apollo mission assignment program without a Saturn I.

- MSFC had been asking OMSF concurrence in including a restart capability in the S-IVB (second) stage during the Saturn IB program.

1963 October 30 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn IB.

- Manned Saturn I earth orbital flights canceled - .

Nation: USA.

Related Persons: Mueller,

Webb.

Program: Apollo.

Spacecraft: Apollo Lunar Landing.

NASA canceled four manned earth orbital flights with the Saturn I launch vehicle. Six of a series of 10 unmanned Saturn I development flights were still scheduled. Development of the Saturn IB for manned flight would be accelerated and "all-up" testing would be started. This action followed Bellcomm's recommendation of a number of changes in the Apollo spacecraft flight test program. The program should be transferred from Saturn I to Saturn IB launch vehicles; the Saturn I program should end with flight SA-10. All Saturn IB flights, beginning with SA-201, should carry operational spacecraft, including equipment for extensive testing of the spacecraft systems in earth orbit.

Associate Administrator for Manned Space Flight George E. Mueller had recommended the changeover from the Saturn I to the Saturn IB to NASA Administrator James E. Webb on October 26. Webb's concurrence came two days later.

1963 November 8 - . LV Family: Saturn I. Launch Vehicle: Saturn IB.

- Uprated H-1 engine for the first stage of the Saturn IB - .

Nation: USA.

Program: Apollo.

MSFC directed Rocketdyne to develop an uprated H-1 engine to be used in the first stage of the Saturn IB. In August, Rocketdyne had proposed that the H-1 be uprated from 85,275 to 90,718 kilograms (188,000 to 200,000 pounds) of thrust. The uprated engine promised a 907-kilogram (2,000 pound) increase in the Saturn IB's orbital payload, yet required no major systems changes and only minor structural modifications.

1964 January 29 - . 16:25 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC37B. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn 5 - .

Payload: Saturn-SA 5. Mass: 17,100 kg (37,600 lb). Nation: USA.

Agency: NASA Huntsville.

Program: Apollo.

Class: Technology.

Type: Re-entry test vehicle. Spacecraft: Jupiter nose cone.

Decay Date: 1966-04-30 . USAF Sat Cat: 744 . COSPAR: 1964-005A. Apogee: 740 km (450 mi). Perigee: 274 km (170 mi). Inclination: 31.40 deg. Period: 94.80 min.

First first mission of Block II Saturn with two live stages. SA-5, a vehicle development flight, was launched from Cape Kennedy Complex 37B at 11:25:01.41, e.s.t. This was the first flight of the Saturn I Block II configuration (i.e., lengthened fuel tanks in the S-1 and stabilizing tail fins), as well as the first flight of a live (powered) S-IV upper stage. The S-1, powered by eight H-1 engines, reached a full thrust of over 680,400 kilograms (1.5 million pounds) the first time in flight. The S-IV's 41,000 kilogram (90,000-pound-thrust cluster of six liquid-hydrogen RL-10 engines performed as expected. The Block II SA-5 was also the first flight test of the Saturn I guidance system.

1964 February 6 - . Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- American challenge - .

Nation: Russia.

Related Persons: Popovich,

Tereshkova.

Program: Lunar L1.

Popovich has left on a tour of Australia, and Tereshkova is in England. The propaganda front of the Soviet space program is going well. But Kamanin is disquieted by the American testing of the Saturn I rocket. Its 17 tonne payload is more than double that of any Soviet booster. Greater efforts are needed, instead he is wasting his time editing Tereshkova's new book...

1964 May 28 - . LV Family: Saturn I, Saturn V. Launch Vehicle: Saturn INT-27, Saturn V-25(S)B, Saturn V-25(S)U.

- 156-inch solid-propellant rocket motor fired for the first time. - .

Lockheed Propulsion Company test fired a 156-inch diameter, solid-propellant rocket motor for the first time. The one-segment test motor (156-3-L), with tab jet thrust vector control, produced more than 900,000 pounds of thrust during its 110-second firing. The test was conducted as part of the Space Systems Division's Large Solid Rocket Motor research and development program (Program 623A).

1964 May 28 - . 17:07 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC37B. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn 6 - . Payload: Apollo CSM Boilerplate 13. Mass: 16,900 kg (37,200 lb). Nation: USA. Agency: NASA Houston. Program: Apollo. Class: Moon. Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Structural. Decay Date: 1964-06-01 . USAF Sat Cat: 800 . COSPAR: 1964-025A. Apogee: 204 km (126 mi). Perigee: 179 km (111 mi). Inclination: 31.70 deg. Period: 88.20 min. Apollo Saturn Mission A-101, using CM BP-13 atop SA-6 Saturn I launch vehicle, launched at Cape Kennedy, Fla., to prove spacecraft/launch vehicle compatibility. Boilerplate CSM, LM adapter, LES. LES jettison demonstrated..

1964 September 18 - . 16:22 GMT - . Launch Site: Cape Canaveral. Launch Complex: Cape Canaveral LC37B. Launch Vehicle: Saturn I.

- Saturn 7 - . Payload: Apollo CSM Boilerplate 15. Mass: 16,700 kg (36,800 lb). Nation: USA. Agency: NASA Houston. Program: Apollo. Class: Moon. Type: Manned lunar spacecraft. Spacecraft Bus: Apollo. Spacecraft: Apollo CSM, CSM Structural. Decay Date: 1964-09-22 . USAF Sat Cat: 883 . COSPAR: 1964-057A. Apogee: 215 km (133 mi). Perigee: 181 km (112 mi). Inclination: 31.70 deg. Period: 88.50 min. Apollo systems test. Third orbital test. First closed-loop guidance test..

1964 September 30 - . LV Family: Saturn I.

- Second test firing of a 156-inch diameter, solid-propellant motor. - . In a second test firing, Lockheed Propulsion Company fired a 156-inch diameter, solid-propellant motor (156-4-L) for 140 seconds, and it produced over one million pounds of thrust..

1964 December 12 - . LV Family: Saturn I.

- First 156-inch solid rocket motor fired - .