The World Wide Web turned 25 last week. Happy birthday!

As is so often the case when web history is being discussed, there is much conflating of “the web” and “the internet” in some mainstream media outlets. The internet—the network of networks that allows computers to talk to each other across the globe—is older than 25 years. The web—a messy collection of HTML files linked via URLs and delivered with the Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP)—is just one of the many types of information services that uses the pipes of the internet (yes, pipes …or tubes, if you prefer—anything but “cloud”).

Now, some will counter that although the internet and the web are technically different things, for most people they are practically the same, because the web is by far the most common use-case for the internet in everyday life. But I’m not so sure that’s true. Email is a massive part of the everyday life of many people—for some poor souls, email usage outweighs web usage. Then there’s streaming video services like Netflix, and voice-over-IP services like Skype. These sorts of proprietary protocols make up an enormous chunk of the internet’s traffic.

The reason I’m making this pedantic distinction is that there’s been a lot of talk in the past year about keeping the web open. I’m certainly in agreement on that front. But if you dig deeper, it turns out that most of the attack vectors are at the level of the internet, not the web.

Net neutrality is hugely important for the web …but it’s hugely important for every other kind of traffic on the internet too.

The Snowden revelations have shown just how shockingly damaging the activities of the NSA and GCHQ are …to the internet. But most of the communication protocols they’re intercepting are not web-based. The big exception is SSL, and the fact that they even thought it would be desirable to attempt to break it shows just how badly they need to be stopped—that’s the mindset of a criminal organisation, pure and simple.

So, yes, we are under attack, but let’s be clear about where those attacks are targeted. The internet is under attack, not the web. Not that that’s a very comforting thought; without a free and open internet, there can be no World Wide Web.

But by and large, the web trundles along, making incremental improvements to itself: expanding the vocabulary of HTML, updating the capabilities of HTTP, clarifying the documentation of URLs. Forgive my anthropomorphism. The web, of course, does nothing to itself; people are improving the web. But the web always has been—and always will be—people.

For some time now, my primary concern for the web has centred around what I see as its killer feature—the potential for long-term storage of knowledge. Yes, the web can be (and is) used for real-time planet-spanning communication, but there are plenty of other internet technologies that can do that. But the ability to place a resource at a URL and then to access that same resource at that same URL after many years have passed …that’s astounding!

Using any web browser on any internet-enabled device, you can instantly reach the first web page ever published. 23 years on, it’s still accessible. That really is something special. Digital information is not usually so long-lived.

On the 25th anniversary of the web, I was up in London with the rest of the Clearleft gang. Some of us were lucky enough to get a behind-the-scenes peak at the digital preservation work being done at the British Library:

In a small, unassuming office, entire hard drives, CD-ROMs and floppy disks are archived, with each item meticulously photographed to ensure any handwritten notes are retained. The wonderfully named ‘ancestral computing’ corner of the office contains an array of different computer drives, including 8-inch, 5 1⁄4-inch, and 3 1⁄2-inch floppy disks.

Most of the data that they’re dealing with isn’t much older than the web, but it’s an order of magnitude more difficult to access; trapped in old proprietary word-processing formats, stuck on dying storage media, readable only by specialised hardware.

Standing there looking at how much work it takes to rescue our cultural heritage from its proprietary digital shackles, I was struck once again by the potential power of the web. With such simple components—HTML, HTTP, and URLs—we have the opportunity to take full advantage of the planet-spanning reach of the internet, without sacrificing long-term access.

As long as we don’t screw it up.

Right now, we’re screwing it up all the time. The simplest way that we screw it up is by taking it for granted. Every time we mindlessly repeat the fallacy that “the internet never forgets,” we are screwing it up. Every time we trust some profit-motivated third-party service to be custodian of our writings, our images, our hopes, our fears, our dreams, we are screwing it up.

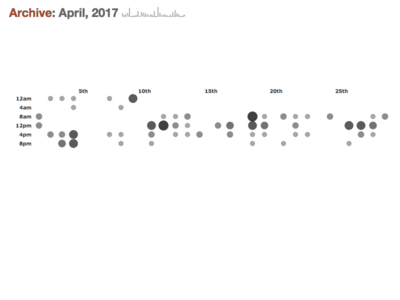

The evening after the 25th birthday of the web, I was up in London again. I managed to briefly make it along to the 100th edition of Pub Standards. It was a long time coming. In fact, there was a listing on Upcoming.org for the event. The listing was posted on February 5th, 2007.

Of course, you can’t see the original URL of that listing. Upcoming.org was “sunsetted” by Yahoo, the same company that “sunsetted” Geocities in much the same way that the Enola Gay sunsetted Hiroshima. But here’s a copy of that listing.

Fittingly, there was an auction held at Pub Standards 100 in aid of the Internet Archive. The schwag of many a “sunsetted” startup was sold off to the highest bidder. I threw some of my old T-shirts into the ring and managed to raise around £80 for Brewster Kahle’s excellent endeavour. My old Twitter shirt went for a pretty penny.

I was originally planning to bring my old Pownce T-shirt along too. But at the last minute, I decided I couldn’t part with it. The pain is still too fresh. Also, it serves a nice reminder for me. Trusting any third-party service—even one as lovely as Pownce—inevitably leads to destruction and disappointment.

That’s another killer feature of the web: you don’t need anyone else. You can publish to this world-changing creation without asking anyone for permission. I wish it were easier for people to do this: entrusting your heritage to the Yahoos and Pownces of the world is seductively simple …but only in the short term.

In 25 years time, I want to be able to access these words at this URL. I’m going to work to make that happen.