|

By Kathryn Westcott

BBC News

|

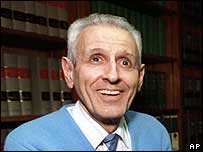

Jack Kevorkian - once America's most ardent advocate of physician-assisted suicide for terminally ill patients - has ended an eight-year prison sentence apparently determined to wade right back into the right-to-die debate.

Kevorkian says his campaign will continue but within the laws

|

The 79-year-old retired pathologist's release is likely to push the assisted suicide issue back to prominence. According to reports, Kevorkian's lawyer says his client has been offered lucrative public speaking contracts.

Throughout the 1990s, Kevorkian waged a defiant campaign to help people end their lives.

His "suicide machine" - an instrument that allowed patients to inject themselves intravenously with a lethal dose of potassium chloride - became notorious.

The man who came to be known as "Dr Death" was linked to about 130 deaths, and was charged, tried and cleared in three assisted-suicide cases.

He was finally convicted of murder in 1999 after injecting a lethal dose himself for the first time, into a patient suffering from a wasting disease.

Showdown

For Kevorkian - who allowed the procedure to be videotaped and broadcast on national television - this was an attempt to prompt a legal showdown on the issue.

|

LEGAL BATTLES

Vermont: Death-with-dignity bill failed in 2005 and 2007

Hawaii: Came within three votes of becoming the second state to allow doctor-assisted suicide in 2002. Similar bills have stalled in the legislature since then

Michigan: A law enacted in 1998 made physician-assisted suicide a felony

Washington State: Voters in 1991 rejected a proposal to allow doctor-assisted suicide. This would have overturned an existing ban.

Maine: Voters narrowly rejected a proposal in 2000. Similar proposals were rejected by the legislature four times before supporters launched a citizen initiative drive that forced the proposal to the ballot

Source: The Associated Press

|

Kevorkian's campaign sparked a nationwide debate about patients' right to die and the role that physicians should play.

Oregon is the only state, so far, to have legalised the procedure. Now Kevorkian wants to promote more Oregon-like legislation.

"It's got to be legalised," he told a Detroit TV station in a phone interview a few days before his release from prison in Michigan.

"That's the point. I'll work to have it legalised, but I won't break any laws doing it."

Kevorkian appears to maintain relatively strong public support.

An AP-Ipsos poll released this week found that 53% of those surveyed thought he should not have been jailed, while 40% supported his imprisonment.

The poll also asked whether it should be legal for doctors to prescribe lethal drugs to help terminally ill patients end their own lives: 48% agreed while 44% said it should be illegal.

California's bid

Peg Sandeen, executive director of the Death with Dignity National Centre, told the BBC News website that the absence of right-to-die legislation was "dangerous".

|

LEGAL IN EUROPE IN:

Switzerland: Physician and non-physician assisted suicide only

Belgium: Permits 'euthanasia' but does not define the method

Netherlands: Voluntary euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide lawful since April 2002

|

"We know that covert and clandestine aid in dying happens every day - studies show that it is prevalent across the country," she says.

Oregon could get some big company soon. The spotlight is now on California, where a bill under consideration would allow patients diagnosed with six months or less to live to take lethal pills prescribed by their doctor.

David Masci of the independent Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life believes the bill has a chance to pass the state legislature this year because it has the backing of the assembly speaker, Fabian Nunez

"That could carry the bill through the assembly and give it some momentum in the state senate," he told the BBC News website.

If both houses approve the bill, it will need Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger's signature to become law.

He has previously said he would prefer the issue be decided by voter referendum rather than the legislature.

A poll found last year that nearly 70% of Californian adults favoured allowing incurably ill patients access to lethal drugs.

Local priorities

A successful passage of the bill would be important on a national scale, says Mr Masci. California, the nation's most populous state, has always been a social and cultural bellwether. It could prompt other state legislatures to debate the issue, he says.

But Wesley J Smith, author and leading campaigner against assisted suicide, does not believe the bill has a chance of passing this year.

"I think the opposition has been able to mount a stalwart and coordinated effort to defeat the bill in the assembly," he told the BBC News website.

"I think most legislators know that the push for assisted suicide comes from a relatively small, if influential, sector of society, and thus are not worried that opposing legalisation will hurt them politically. It is just not a high priority item for most voters or politicians."

Oregon's experience

The Oregon precedent is a battleground for campaigners on both sides of the debate in California.

According to the Oregon Department of Human Services, 292 patients have died under the terms of the law between 1997 and 2006. Proof, say supporters, that fears of the law leading to widespread euthanasia are ill-founded.

But opponents say the figures do not tell the whole story.

Oregon's rules governing assisted suicides stipulate that the patient must have been declared terminally ill by two physicians, have a life expectancy of six months or less and must have requested lethal drugs three times.

Opponents claim that there is no state authority to check fully on this and it is, therefore, open to abuse. Because Oregon does not require autopsies in such cases, they say, there is no way of knowing the patient's actual underlying conditions.

"It does not penalise doctors who fail to report assisting suicides and the state destroys the records and its paperwork after each annual report, making it impossible to verify those reports' conclusions independently," Tim Rosales, spokesman for Californians Against Assisted Suicide (CAAS), said in a recent statement.

But Patty Berg, co-author of California's bill and member of the assembly, says there are no facts to back up the claim that the Oregon law has been open to abuse.

"When that state's data disproves their warnings, they say the data is flawed," she told the BBC News website.

Euthanasia fears

CAAS - a coalition of disability rights activists, Latino civil rights groups, pro-life groups and medical professionals - is leading the opposition in California.

The group fears that rising health care costs and health rationing could lead hospitals, health insurers and even family members to pressure patients to end their lives prematurely in order to save scare resources.

The California Assembly is scheduled to vote on the bill in the next few days. Kevorkian's shadow could loom large.

"In a way, Dr Kevorkian is the poster boy for why we need this law," says Ms Berg.

"The disturbing tale of Dr Kevorkian is a tale of the tragic lengths people will go to when they have no legal options.

~RS~q~RS~~RS~z~RS~10~RS~)