|

Joan Baxter

Former BBC correspondent, Bamako, Mali

|

Ali Farka Toure was one of the pioneers of "Mali Blues"

|

More than anything else, Ali Farka Toure wanted to show me his farm. At first I did not understand why.

I had come to his home to find out why he had turned his back on the glamour and luxury that was his for the taking after he won his first Grammy award and the world "discovered" the Malian Blues man.

I wanted to know why he had moved back to his native village, Niafunke, about 80km (50 miles) upstream from the fabled ancient city of Timbuktu on the Niger River.

Instead of answering my questions, Ali Farka insisted we take a trip in his river canoe to see what he was cultivating in the dry and sandy soils of northern Mali.

'Giving back'

To me, his farm did not look all that promising. I had trouble keeping up with him as he strode across the barren, windswept fields where he said he would produce irrigated rice.

|

That other life was a bit like dried dung; it didn't stick to my shoes. Whatever I produce it stays here

That other life was a bit like dried dung; it didn't stick to my shoes. Whatever I produce it stays here

|

The desert winds had killed his banana plants and 1,500 fruit trees in a would-be orchard. The potatoes he dug up with his bare hands had been devoured by termites.

None of this seemed to dampen his enthusiasm for his 40-hectare (99-acre) farm, which he said would transform the area into a food basket, and feed his extended family and dozens of other people in Niafunke.

Although he did not tell me himself, I had learned he had also spent his own money grading the roads, putting in sewer canals and fuelling a generator that provided the impoverished town with electricity.

He told me his money was "all gone". He did not seem particularly worried about it.

|

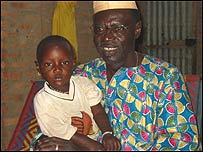

We would have dinner with him, and listen to him share his experiences, always with a laugh and smile

We would have dinner with him, and listen to him share his experiences, always with a laugh and smile

|

It was not until we were on our way back across the river that I began to understand what Ali Farka had been trying to tell me during the trip to his farm.

We were coasting towards the shore, the sun was glinting off the sand dunes that lined the river, and the hot wind was whipping up ripples in the green water lapping at the canoe.

Sitting on a wooden strut, staring out at the river, Ali Farka picked up his guitar and began to play.

A generous spirit

Instantly his face lit up with a huge and irrepressible smile. The tune was Hawa Dolo, from his album The Source.

Ali Farka had just finished work on a new solo album when he died

|

He said all his music came from the depths of the Niger, from the river spirit he called Jimbala.

Then he finally used words to explain why he had come home to stay.

"This life is better," he said. "That other life was a bit like dried dung; it didn't stick to my shoes. Whatever I produce it stays here.

"If God gives me big buildings in the United States or Canada or Japan or Sydney or Germany, can I put them in my pocket and bring them back? No, it's impossible."

He said he was working to improve the life of his family and to live in solidarity with others.

"If I eat, they eat. What I drink, they drink. What I wear, they wear. And I live with the river all the time," he said.

Still picking out haunting melodies on his guitar, he added: "Without the river spirit I would be deaf and have no voice. I would cease to be."