|

By Becky Branford

BBC News

|

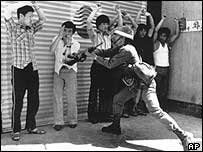

The soldiers' open brutality drew outraged residents into the struggle

|

A quarter of a century on, Koreans are remembering one of the ugliest episodes in their history.

In May 1980, hundreds of civilians were massacred by soldiers in the south-western city of Kwangju after rising up against military rule.

Although it was brutally put down, the Kwangju Uprising is now seen by many as a pivotal moment in the South Korean struggle for democracy in the long period of dictatorship following the Korean war.

And some contend the uprising had important ramifications which are still being felt now, both inside Korea and beyond its borders.

There is a sombre monument and museum dedicated to the massacre in Kwangju, and the anniversary of the beginning of the siege on 18 May is now a public holiday in Korea.

Batons and bayonets

The protests in Kwangju in the spring of 1980 were not unusual.

The country was being swept by a tide of demonstrations, mainly by students, in the wake of the assassination of the dictator Park Chung Hee and the military coup which brought General Chun Doo-hwan to power in his place.

It was the sheer, open brutality of the response of Korean paratroops which proved decisive.

The paratroops charged crowds with batons and bayonets, stripped students and other citizens down to their underwear in the streets before beating them, and fired indiscriminately into crowds.

This brutality drew outraged ordinary citizens into the struggle, creating a mass movement of resistance which forced the military to retreat from the city for five days, leaving the city in full control of the residents.

The military retook the city on 27 May, crushing the citizens' resistance in an overwhelming show of force.

The final toll of those who lost their lives is still unknown, as it is believed the military dumped bodies in mass graves or lakes. Estimates today range from 500 to 2,000.

'No-one left'

Hwang Sok-yong is one of Korea's best-known novelists, and was a leading young dissident who lived in Kwangju at the time of the uprising.

The citizens of Kwangju took control of the city for five days

|

He was away at the time the siege began, and then went into hiding while authorities rounded up thousands of people they suspected of dissident activities.

"Six months later, I went back to my home in Kwangju," Mr Hwang told the BBC News website, "and nobody was there. Everybody was in prison, or had died, or had run away.

"My young friends, many of them died."

Many of those who escaped or survived say they still bear physical and psychological scars from the massacre, or feel guilty they lived when friends and family died.

Around the country, military reprisals against perceived agitators followed in the immediate aftermath of the massacre.

Dawn of democracy

But commentators are agreed that in the longer term the Kwangju massacre played a hugely important role in forcing Korean authorities finally to begin adopting democratic reforms in 1987.

"What started in 1980 ended in 1987," says Mr Hwang.

"The Kwangju Uprising lit the fuse of the dynamite stick of democracy."

The uprising, he explains, mobilised ordinary citizens to join a struggle which until then had been mostly confined to students and dissidents.

"It was the birth of citizenship. It was the beginning of a western-style civil society - and Korean modernity," he said.

All three Korean presidents selected in the country's fully democratic elections have been aligned with the pro-democracy movements of which Kwangju became emblematic.

The election of Kim Dae-jung in 1998 seemed particularly symbolic. From a town in the same Cholla province as Kwangju, Mr Kim was arrested on charges of sedition in May 1980 - an additional spur to those who participated in the uprising.

American antipathy

The experience in Kwangju also firmly yoked Koreans' struggle for liberation from dictatorship with a conviction they must also distance themselves from US control, commentators say.

Since the Korean war, tens of thousands of US troops have been stationed in the South and at the time of the Kwangju uprising, a US general retained ultimate operational control over combined US and South Korean forces.

Chun Doo-hwan was jailed and then pardoned for his role in the massacre

|

"The US had been supporting Park Chung Hee since [he took power] in 1961, and it did nothing as Chun Doo-hwan seized power," Bruce Cumings, professor of history at the University of Chicago and a prominent Korea expert, told the BBC News website.

"It was as plain as the nose on anyone's face that the US was supporting Park Chung Hee and then his protege, and it was much more worried about stability and North Korea than it was about democracy in the South.

"Kwangju just poisoned relations with the US."

He says that while authorities in South Korea have gone to extensive lengths to document what happened in Kwangju, Washington has never conducted "a serious investigation" into the US role in the massacre.

Northern warming

While Koreans were questioning the US role in Korean affairs, they were also challenging national hostility to North Korea, says Mr Hwang.

"It started people thinking about 'us and them'. Who are we? Who are they? The Korean special troops were part of the US military, people started thinking, but North Korea is part of us.

"Their attitude changed. It encouraged negotiation and co-operation with North Korea."

This softer approach would eventually result in Kim Dae-jung's "sunshine policy" of engagement with the North.

Twenty-five years on, some Koreans express fear that Korean schoolchildren are beginning to forget the sacrifice of those who died in Kwangju.