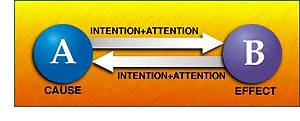

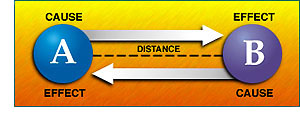

Let us now more closely examine several components of communication by looking at two life units, one of them “A” and the other “B.” “A” and “B” are terminals – by terminal we mean a point that receives, relays and sends communication.

First there is “A’s” intention. This, at “B” becomes attention, and for a true communication to take place, a duplication at “B” must take place of what emanated from “A”.

“A” of course, to emanate a communication, must have given attention originally to “B”, and “B” must have given to this communication some intention, at least to listen or receive, so we have both cause and effect having intention and attention.

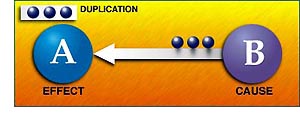

Now, there is another factor which is very important. This is the factor of duplication. We could express this as reality, or we could express it as agreement. The degree of agreement reached between “A” and “B” in this communication cycle becomes their reality, and this is accomplished mechanically by duplication. In other words, the degree of reality reached in this communication cycle depends upon the amount of duplication. “B” as effect, must to some degree duplicate what emanated from “A” as cause, in order for the first part of the cycle to take effect.

Then “A”, now as effect, must duplicate what emanated from “B” for the communication to be concluded. If this is done there is no detrimental consequence.

If this duplication does not take place at “B” and then at “A” we get what amounts to an unfinished cycle of action. If, for instance, “B” did not vaguely duplicate what emanated from “A”, the first part of the cycle of communication was not achieved, and a great deal of randomity (unpredicted motion), explanation, argument might result. Then if “A” did not duplicate what emanated from “B” when “B” was cause on the second cycle, again an uncompleted cycle of communication occurred with consequent unreality. Now naturally, if we cut down reality, we will cut down affinity – the feeling of love or liking for something or someone. So, where duplication is absent, affinity is seen to drop.

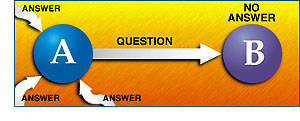

A complete cycle of communication will result in high affinity. If we disarrange any of these factors we get an incomplete cycle of communication and we have either “A” or “B” or both waiting for the end of cycle. In such a wise the communication becomes harmful.

An unfinished cycle of communication generates what might be called answer hunger. An individual who is waiting for a signal that his communication has been received is prone to accept any inflow. When an individual has, for a very long period of time, consistently waited for answers which did not arrive, any sort of answer from anywhere will be pulled in to him, by him, as an effort to remedy his scarcity for answers.

Uncompleted cycles of communication bring about a scarcity of answers. It does not much matter what the answers were or would be as long as they vaguely approximate the subject at hand. It does matter when some entirely unlooked-for answer is given, as in compulsive or obsessive communication, or when no answer is given at all.

Communication itself is detrimental only when the emanating communication at cause was sudden and non sequitur (illogical) to the environment. Here we have violations of attention and intention.

The factor of interest also enters here but is far less important. Nevertheless, it explains a great deal about human behavior. “A” has the intention of interesting “B”. “B”, to be talked to, becomes interesting.

Similarly “B”, when he emanates a communication, is interested and “A” is interesting.

Here we have, as part of the communication formula (but a less important part), the continuous shift from being interested to being interesting on the part of either of the terminals, “A” or “B”. Cause is interested, effect is interesting.

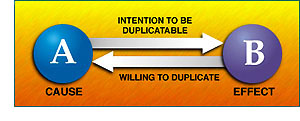

Of some greater importance is the fact that the intention to be received on the part of “A” places upon “A” the necessity of being duplicatable.

If “A” cannot be duplicatable in any degree, then of course his communication will not be received at “B”, for “B”, unable to duplicate “A”, cannot receive the communication.

As an example of this, “A”, let us say, speaks in Chinese, where “B” can only understand French. It is necessary for “A” to make himself duplicatable by speaking French to “B” who only understands French. In a case where “A” speaks one language and “B” another, and they have no language in common, we have the factor of mimicry possible and a communication can yet take place. “A”, supposing he had a hand, could raise his hand. “B”, supposing he had one, could raise his hand. Then “B” could raise his other hand, and “A” could raise his other hand, and we would have completed a cycle of communication by mimicry.

Basically, all things are considerations. We consider that things are, and so they are. The idea is always senior to the mechanics of energy, space, time, mass. It would be possible to have entirely different ideas about communication than these. However, these happen to be the ideas of communication which are in common in this universe, and which are utilized by the life units of this universe.

Here we have the basic agreement upon the subject of communication in the communication formula as given here. Because ideas are senior to this, a being can get, in addition to the communication formula, a peculiar idea concerning just exactly how communication should be conducted, and if this is not generally agreed upon, can find himself definitely out of communication.

Let us take the example of a modernistic writer who insists that the first three letters of every word should be dropped or that no sentence should be finished. He will not attain agreement among his readers.

There is a continuous action of natural selection, one might say, which weeds out strange or peculiar communication ideas. People, to be in communication, adhere to the basic rules as given here, and when anyone tries to depart too widely from these rules, they simply do not duplicate him and so, in effect, he goes out of communication.

Now we come to the problem of what a life unit must be willing to experience in order to communicate. In the first place the primary source-point must be willing to be duplicatable. It must be able to give at least some attention to the receipt-point. The primary receipt-point must be willing to duplicate, must be willing to receive and must be willing to change into a source-point in order to send the communication, or an answer to it, back. And the primary source-point in its turn must be willing to be a receipt-point.

As we are dealing basically with ideas and not mechanics, we see, then, that a state of mind must exist between a cause- and effect-point whereby each one is willing to be cause or effect at will, is willing to duplicate at will, is willing to be duplicatable at will, is willing to change at will, is willing to experience the distance between, and, in short, willing to communicate.

Where we get these conditions in an individual or a group we have sane people.

Where an unwillingness to send or receive communications occurs, where people obsessively or compulsively send communications without direction and without trying to be duplicatable, where individuals in receipt of communications stand silent and do not acknowledge or reply, we have factors of irrationality.

Some of the conditions which can occur in an irrational line are a failure to be duplicatable before one emanates a communication, an intention contrary to being received, an unwillingness to receive or duplicate a communication, an unwillingness to experience distance, an unwillingness to change, an unwillingness to give attention, an unwillingness to express intention, an unwillingness to acknowledge, and, in general, an unwillingness to duplicate.

It might be seen by someone that the solution to communication is not to communicate. One might say that if he hadn’t communicated in the first place he wouldn’t be in trouble now. Perhaps there is some truth in this, but a man is as dead as he can’t communicate. He is as alive as he can communicate.