Particles / Instancing

Particles are very similar to 3D billboards. There are two major differences, though :

- there is usually a LOT of them

- they move

- the appear and die.

- they are semi-transparent

Both of these difference come with problems. This tutorial will present ONE way to solve them; there are many other possibilities.

Particles, lots of them !

The first idea to draw many particles would be to use the previous tutorial’s code, and call glDrawArrays once for each particle. This is a very bad idea, because this means that all your shiny GTX’ 512+ multiprocessors will all be dedicated to draw ONE quad (obviously, only one will be used, so that’s 99% efficiency loss). Then you will draw the second billboard, and it will be the same.

Clearly, we need a way to draw all particles at the same time.

There are many ways to do this; here are three of them :

- Generate a single VBO with all the particles in them. Easy, effective, works on all platforms.

- Use geometry shaders. Not in the scope of this tutorial, mostly because 50% of the computers don’t support this.

- Use instancing. Not available on ALL computers, but a vast majority of them.

In this tutorial, we’ll use the 3rd option, because it is a nice balance between performance and availability, and on top of that, it’s easy to add support for the first method once this one works.

Instancing

“Instancing” means that we have a base mesh (in our case, a simple quad of 2 triangles), but many instances of this quad.

Technically, it’s done via several buffers :

- Some of them describe the base mesh

- Some of them describe the particularities of each instance of the base mesh.

You have many, many options on what to put in each buffer. In our simple case, we have :

- One buffer for the vertices of the mesh. No index buffer, so it’s 6 vec3, which make 2 triangles, which make 1 quad.

- One buffer for the particles’ centers.

- One buffer for the particles’ colors.

These are very standard buffers. They are created this way :

// The VBO containing the 4 vertices of the particles.

// Thanks to instancing, they will be shared by all particles.

static const GLfloat g_vertex_buffer_data[] = {

-0.5f, -0.5f, 0.0f,

0.5f, -0.5f, 0.0f,

-0.5f, 0.5f, 0.0f,

0.5f, 0.5f, 0.0f,

};

GLuint billboard_vertex_buffer;

glGenBuffers(1, &billboard_vertex_buffer);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, billboard_vertex_buffer);

glBufferData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, sizeof(g_vertex_buffer_data), g_vertex_buffer_data, GL_STATIC_DRAW);

// The VBO containing the positions and sizes of the particles

GLuint particles_position_buffer;

glGenBuffers(1, &particles_position_buffer);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, particles_position_buffer);

// Initialize with empty (NULL) buffer : it will be updated later, each frame.

glBufferData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, MaxParticles * 4 * sizeof(GLfloat), NULL, GL_STREAM_DRAW);

// The VBO containing the colors of the particles

GLuint particles_color_buffer;

glGenBuffers(1, &particles_color_buffer);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, particles_color_buffer);

// Initialize with empty (NULL) buffer : it will be updated later, each frame.

glBufferData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, MaxParticles * 4 * sizeof(GLubyte), NULL, GL_STREAM_DRAW);

, which is as usual. They are updated this way :

// Update the buffers that OpenGL uses for rendering.

// There are much more sophisticated means to stream data from the CPU to the GPU,

// but this is outside the scope of this tutorial.

// http://www.opengl.org/wiki/Buffer_Object_Streaming

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, particles_position_buffer);

glBufferData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, MaxParticles * 4 * sizeof(GLfloat), NULL, GL_STREAM_DRAW); // Buffer orphaning, a common way to improve streaming perf. See above link for details.

glBufferSubData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, 0, ParticlesCount * sizeof(GLfloat) * 4, g_particule_position_size_data);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, particles_color_buffer);

glBufferData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, MaxParticles * 4 * sizeof(GLubyte), NULL, GL_STREAM_DRAW); // Buffer orphaning, a common way to improve streaming perf. See above link for details.

glBufferSubData(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, 0, ParticlesCount * sizeof(GLubyte) * 4, g_particule_color_data);

, which is as usual. Before render, they are bound this way :

// 1rst attribute buffer : vertices

glEnableVertexAttribArray(0);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, billboard_vertex_buffer);

glVertexAttribPointer(

0, // attribute. No particular reason for 0, but must match the layout in the shader.

3, // size

GL_FLOAT, // type

GL_FALSE, // normalized?

0, // stride

(void*)0 // array buffer offset

);

// 2nd attribute buffer : positions of particles' centers

glEnableVertexAttribArray(1);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, particles_position_buffer);

glVertexAttribPointer(

1, // attribute. No particular reason for 1, but must match the layout in the shader.

4, // size : x + y + z + size => 4

GL_FLOAT, // type

GL_FALSE, // normalized?

0, // stride

(void*)0 // array buffer offset

);

// 3rd attribute buffer : particles' colors

glEnableVertexAttribArray(2);

glBindBuffer(GL_ARRAY_BUFFER, particles_color_buffer);

glVertexAttribPointer(

2, // attribute. No particular reason for 1, but must match the layout in the shader.

4, // size : r + g + b + a => 4

GL_UNSIGNED_BYTE, // type

GL_TRUE, // normalized? *** YES, this means that the unsigned char[4] will be accessible with a vec4 (floats) in the shader ***

0, // stride

(void*)0 // array buffer offset

);

, which is as usual. The difference comes when rendering. Instead of using glDrawArrays (or glDrawElements if your base mesh has an index buffer), you use glDrawArrraysInstanced / glDrawElementsInstanced, which is equivalent to calling glDrawArrays N times (N is the last parameter, in our case ParticlesCount) :

glDrawArraysInstanced(GL_TRIANGLE_STRIP, 0, 4, ParticlesCount);

Bue something is missing here. We didn’t tell OpenGL which buffer was for the base mesh, and which were for the different instances. This is done with glVertexAttribDivisor. Here’s the full commented code :

// These functions are specific to glDrawArrays*Instanced*.

// The first parameter is the attribute buffer we're talking about.

// The second parameter is the "rate at which generic vertex attributes advance when rendering multiple instances"

// http://www.opengl.org/sdk/docs/man/xhtml/glVertexAttribDivisor.xml

glVertexAttribDivisor(0, 0); // particles vertices : always reuse the same 4 vertices -> 0

glVertexAttribDivisor(1, 1); // positions : one per quad (its center) -> 1

glVertexAttribDivisor(2, 1); // color : one per quad -> 1

// Draw the particules !

// This draws many times a small triangle_strip (which looks like a quad).

// This is equivalent to :

// for(i in ParticlesCount) : glDrawArrays(GL_TRIANGLE_STRIP, 0, 4),

// but faster.

glDrawArraysInstanced(GL_TRIANGLE_STRIP, 0, 4, ParticlesCount);

As you can see, instancing is very versatile, because you can pass any integer as the AttribDivisor. For instance, with glVertexAttribDivisor(2, 10), each 10 subsequent instances will have the same color.

What’s the point ?

The point is that now, we only have to update a small buffer each frame (the center of the particles) and not a huge mesh. This is a x4 bandwidth gain !

Life and death

On the contrary to most other objects in the scene, particles die and born at a very high rate. We need a decently fast way to get new particles and to discard them, something better than “new Particle()”.

Creating new particles

For this, we will have a big particles container :

// CPU representation of a particle

struct Particle{

glm::vec3 pos, speed;

unsigned char r,g,b,a; // Color

float size, angle, weight;

float life; // Remaining life of the particle. if < 0 : dead and unused.

};

const int MaxParticles = 100000;

Particle ParticlesContainer[MaxParticles];

Now, we need a way to create new ones. This function searches linearly in ParticlesContainer, which should be an horrible idea, except that it starts at the last known place, so this function usually returns immediately :

int LastUsedParticle = 0;

// Finds a Particle in ParticlesContainer which isn't used yet.

// (i.e. life < 0);

int FindUnusedParticle(){

for(int i=LastUsedParticle; i<MaxParticles; i++){

if (ParticlesContainer[i].life < 0){

LastUsedParticle = i;

return i;

}

}

for(int i=0; i<LastUsedParticle; i++){

if (ParticlesContainer[i].life < 0){

LastUsedParticle = i;

return i;

}

}

return 0; // All particles are taken, override the first one

}

We can now fill ParticlesContainer[particleIndex] with interesting “life”, “color”, “speed” and “position” values. See the code for details, but you can do pretty much anything here. The only interesting bit is, how many particles should we generate each frame ? This is mostly application-dependant, so let’s say 10000 new particles per second (yes, it’s quite a lot) :

int newparticles = (int)(deltaTime*10000.0);

except that you should probably clamp this to a fixed number :

// Generate 10 new particule each millisecond,

// but limit this to 16 ms (60 fps), or if you have 1 long frame (1sec),

// newparticles will be huge and the next frame even longer.

int newparticles = (int)(deltaTime*10000.0);

if (newparticles > (int)(0.016f*10000.0))

newparticles = (int)(0.016f*10000.0);

Deleting old particles

There’s a trick, see below =)

The main simulation loop

ParticlesContainer contains both active and “dead” particles, but the buffer that we send to the GPU needs to have only living particles.

So we will iterate on each particle, check if it is alive, if it must die, and if everything is allright, add some gravity, and finally copy it in a GPU-specific buffer.

// Simulate all particles

int ParticlesCount = 0;

for(int i=0; i<MaxParticles; i++){

Particle& p = ParticlesContainer[i]; // shortcut

if(p.life > 0.0f){

// Decrease life

p.life -= delta;

if (p.life > 0.0f){

// Simulate simple physics : gravity only, no collisions

p.speed += glm::vec3(0.0f,-9.81f, 0.0f) * (float)delta * 0.5f;

p.pos += p.speed * (float)delta;

p.cameradistance = glm::length2( p.pos - CameraPosition );

//ParticlesContainer[i].pos += glm::vec3(0.0f,10.0f, 0.0f) * (float)delta;

// Fill the GPU buffer

g_particule_position_size_data[4*ParticlesCount+0] = p.pos.x;

g_particule_position_size_data[4*ParticlesCount+1] = p.pos.y;

g_particule_position_size_data[4*ParticlesCount+2] = p.pos.z;

g_particule_position_size_data[4*ParticlesCount+3] = p.size;

g_particule_color_data[4*ParticlesCount+0] = p.r;

g_particule_color_data[4*ParticlesCount+1] = p.g;

g_particule_color_data[4*ParticlesCount+2] = p.b;

g_particule_color_data[4*ParticlesCount+3] = p.a;

}else{

// Particles that just died will be put at the end of the buffer in SortParticles();

p.cameradistance = -1.0f;

}

ParticlesCount++;

}

}

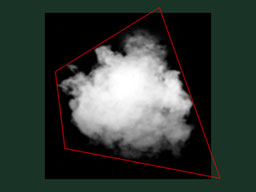

This is what you get. Almost there, but there’s a problem…

Sorting

As explained in Tutorial 10, you need to sort semi-transparent objects from back to front for the blending to be correct.

void SortParticles(){

std::sort(&ParticlesContainer[0], &ParticlesContainer[MaxParticles]);

}

Now, std::sort needs a function that can tell whether a Particle must be put before or after another Particle in the container. This can be done with Particle::operator< :

// CPU representation of a particle

struct Particle{

...

bool operator<(Particle& that){

// Sort in reverse order : far particles drawn first.

return this->cameradistance > that.cameradistance;

}

};

This will make ParticleContainer be sorted, and the particles now display correctly*:

Going further

Animated particles

You can animate your particles’ texture with a texture atlas. Send the age of each particle along with the position, and in the shaders, compute the UVs like we did for the 2D font tutorial. A texture atlas looks like this :

Handling several particle systems

If you need more than one particle system, you have two options : either use a single ParticleContainer, or one per system.

If you have a single container for ALL particles, then you will be able to sort them perfectly. The main drawback is that you’ll have to use the same texture for all particles, which is a big problem. This can be solved by using a texture atlas (one big texture with all your different textures on it, just use different UVs), but it’s not really handy to edit and use.

If you have one container per particle system, on the other hand, particles will only be sorted inside these containers : if two particle sytems overlap, artefacts will start to appear. Depending on your application, this might not be a problem.

Of course, you can also use some kind of hybrid system with several particle systems, each with a (small and manageable) atlas.

Smooth particles

You’ll notice very soon a common artifact : when your particle intersect some geometry, the limit becomes very visible and ugly :

(image from http://www.gamerendering.com/2009/09/16/soft-particles/ )

A common technique to solve this is to test if the currently-drawn fragment is near the Z-Buffer. If so, the fragment is faded out.

However, you’ll have to sample the Z-Buffer, which is not possible with the “normal” Z-Buffer. You need to render your scene in a render target. Alternatively, you can copy the Z-Buffer from one framebuffer to another with glBlitFramebuffer.

http://developer.download.nvidia.com/whitepapers/2007/SDK10/SoftParticles_hi.pdf

Improving fillrate

One of the most limiting factor in modern GPUs is fillrate : the amount of fragments (pixels) it can write in the 16.6ms allowed to get 60 FPS.

This is a problem, because particles typically need a LOT of fillrate, since you can re-draw the same fragment 10 times, each time with another particle; and if you don’t do that, you get the same artifacts as above.

Amongst all the fragments that are written, many are completely useless : these on the border. Your particle textures are often completely transparent on the edges, but the particle’s mesh will still draw them - and update the color buffer with exactly the same value than before.

This small utility computes a mesh (the one you’re supposed to draw with glDrawArraysInstanced() ) that tightly fits your texture :

http://www.humus.name/index.php?page=Cool&ID=8 . Emil Person’s site has plenty of other fascinating articles, too.

Particle physics

At some point, you’ll probably want your particles to interact some more with your world. In particular, particles could rebound on the ground.

You could simply launch a raycast for each particle, between the current position and the future one; we learnt to do this in the Picking tutorials. But this is extremely expensive, you just can’t to this for each particle, each frame.

Depending on your application, you can either approximate your geometry with a set of planes and do the raycast on these planes only; Or, you can use real raycast, but cache the results and approximate nearby collisions with the cache (or, you can do both).

A completely different technique is to use the existing Z-Buffer as a very rough approximation of the (visible) geometry, and collide particles on this. This is “good enough” and fast, but you’ll have to do all your simulation on the GPU, since you can’t access the Z-Buffer on the CPU (at least not fast), so it’s way more complicated.

Here are a few links about these techniques :

http://www.altdevblogaday.com/2012/06/19/hack-day-report/

GPU Simulation

As said above, you can simulate the particles’ movements completely on the GPU. You will still have to manage your particle’s lifecycle on the CPU - at least to spawn them.

You have many options to do this, and none in the scope of this tutorial ; I’ll just give a few pointers.

- Use Transform Feedback. It allows you to store the outputs of a vertex shader in a GPU-side VBO. Store the new positions in this VBO, and next frame, use this VBO as the starting point, and store the new position in the former VBO.

- Same thing but without Transform Feedback: encode your particles’ positions in a texture, and update it with Render-To-Texture.

- Use a General-Purpose GPU library : CUDA or OpenCL, which have interoperability functions with OpenGL.

-

Use a Compute Shader. Cleanest solution, but only available on very recent GPUs.

- Note that for simplicity, in this implementation, ParticleContainer is sorted after updating the GPU buffers. This makes the particles not exactly sorted (there is a one-frame delay), but it’s not really noticeable. You can fix it by splitting the main loop in 2 : Simulate, Sort, and update.