Seeking A Human Spaceflight Program Worthy Of A Great Nation

Review of U.S. Human Spaceflight Plans Committee

Released October 21, 2009

Executive Summary

The U.S. human spaceflight program appears to be on an unsustainable trajectory. It is perpetuating the perilous practice of pursuing goals that do not match allocated resources. Space operations are among the most demanding and unforgiving pursuits ever undertaken by humans. It really is rocket science. Space operations become all the more difficult when means do not match aspirations. Such is the case today.

The nation is facing important decisions on the future of human space flight. Will we leave the close proximity of low-Earth orbit, where astronauts have circled since 1972, and explore the solar system, charting a path for the eventual expansion of human civilization into space? If so, how will we ensure that our exploration delivers the greatest benefit to the nation? Can we explore with reasonable assurances of human safety? Can the nation marshal the resources to embark on the mission?

Whatever space program is ultimately selected, it must be matched with the resources needed for its execution. How can we marshal the necessary resources? There are actually more options available today than in 1961, when President Kennedy challenged the nation to “commit itself to the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the Moon and returning him safely to the Earth.” First, space exploration has become a global enterprise. Many nations have aspirations in space, and the combined annual budgets of their space programs are comparable to NASA’s. If the United States is willing to lead a global program of exploration, sharing both the burden and benefit of space exploration in a meaningful way, significant accomplishments could follow. Actively engaging international partners in a manner adapted to today’s multi-polar world could strengthen geopolitical relationships, leverage global financial and technical resources, and enhance the exploration enterprise.

Second, there is now a burgeoning commercial space industry. If we craft a space architecture to provide opportunities to this industry, there is the potential—not without risk—that the costs to the government would be reduced. Finally, we are also more experienced than in 1961, and able to build on that experience as we design an exploration program. If, after designing cleverly, building alliances with partners, and engaging commercial providers, the nation cannot afford to fund the effort to pursue the goals it would like to embrace, it should accept the disappointment of setting lesser goals. Can we explore with reasonable assurances of human safety? Human space travel has many benefits, but it is an inherently dangerous endeavor. Human safety can never be absolutely assured, but throughout this report, safety is treated as a sine qua non. It is not discussed in extensive detail because any concepts falling short in human safety have simply been eliminated from consideration.

How will we explore to deliver the greatest benefit to the nation? Planning for a human spaceflight program should begin with a choice about its goals—rather than a choice of possible destinations. Destinations should derive from goals, and alternative architectures may be weighed against those goals. There is now a strong consensus in the United States that the next step in human space flight is to travel beyond low-Earth orbit. This should carry important benefits to society, including: driving technological innovation; developing commercial industries and important national capabilities; and contributing to our expertise in further exploration. Human exploration can contribute appropriately to the expansion of scientific knowledge, particularly in areas such as field geology, and it is in the interest of both science and human spaceflight that a credible and well-rationalized strategy of coordination between them be developed. Crucially, human space flight objectives should broadly align with key national objectives.

These more tangible benefits exist within a larger context. Exploration provides an opportunity to demonstrate space leadership while deeply engaging international partners; to inspire the next generation of scientists and engineers; and to shape human perceptions of our place in the universe. The Committee concludes that the ultimate goal of human exploration is to chart a path for human expansion into the solar system. This is an ambitious goal, but one worthy of U.S. leadership in concert with a broad range of international partners.

The Committee’s task was to review the U.S. plans for human spaceflight and to offer possible alternatives. In doing so, it assessed the programs within the current human space-flight portfolio; considered capabilities and technologies a future program might require; and considered the roles of commercial industry and our international partners in this enterprise. From these deliberations, the Committee developed five integrated alternatives for the U.S. human space-flight program, including an executable version of the current program. The considerations and the five alternatives are summarized in the pages that follow.

Key Questions To Guide The Plan For Human Spaceflight

The Committee identified the following questions that, if answered, would form the basis of a plan for U.S. human space flight:

1. What should be the future of the Space Shuttle?

2. What should be the future of the International Space Station (ISS)?

3. On what should the next heavy-lift launch vehicle be based?

4. How should crews be carried to low-Earth orbit?

5. What is the most practicable strategy for exploration beyond low-Earth orbit?

The Committee considers the framing and answering of these questions individually and consistently to be at least as important as their combinations in the integrated options for a human spaceflight program, which are discussed below. Some 3,000 alternatives can be derived from the various possible answers to these questions; these were narrowed to the five representative families of integrated options that are offered in this report. In these five families, the Committee examined the interactions of the decisions, particularly with regard to cost and schedule. Other reasonable and consistent combinations of the choices are possible (each with its own cost and schedule implications), and these could also be considered as alternatives.

Current Programs

Before addressing options for the future human exploration program, it is appropriate to discuss the current programs: the Space Shuttle, the International Space Station and Constellation, as well as the looming problem of “the gap”—the time that will elapse between the scheduled completion of the Space Shuttle program and the advent of a new U.S. capability to lift humans into space.

Space Shuttle

What should be the future of the Space Shuttle? The current plan is to retire it at the end of FY 2010, with its final flight scheduled for the last month of that fiscal year. Although the current administration has relaxed the requirement to complete the last mission before the end of FY 2010, there are no funds in the FY 2011 budget for continuing Shuttle operations.

In considering the future of the Shuttle, the Committee assessed the realism of the current schedule; examined issues related to the Shuttle workforce, reliability and cost; and weighed the risks and possible benefits of a Shuttle extension. The Committee noted that the projected flight rate is nearly twice that of the actual flight rate since return to flight in 2005 after the Columbia accident two years earlier. Recognizing that undue schedule and budget pressure can subtly impose a negative influence on safety, the Committee finds that a more realistic schedule is prudent. With the remaining flights likely to stretch into the second quarter of FY 2011, the Committee considers it important to budget for Shuttle operations through that time.

Although a thorough analysis of Shuttle safety was not part of its charter, the Committee did examine the Shuttle’s safety record and reliability, as well as the results of other reviews of these topics. New human-rated launch vehicles will likely be more reliable once they reach maturity, but in the meantime, the Shuttle is in the enviable position of being through its “infant mortality” phase. Its flight experience and demonstrated reliability should not be discounted.

Once the Shuttle is retired, there will be a gap in the capability of the United States itself to launch humans into space. That gap will extend until the next U.S. human-rated launch system becomes available. The Committee estimates that, under the current plan, this gap will be at least seven years. There has not been this long a gap in U.S. human launch capability since the U.S. human space program began.

Most of the integrated options presented below would retire the Shuttle after a prudent y-out of the current manifest, indicating that the Committee found the interim reliance on international crew services acceptable. However, one option does provide for an extension of the Shuttle at a minimum safe flight rate to preserve U.S. capability to launch astronauts into space. If that option is selected, there should be a thorough review of Shuttle recertification and overall Shuttle reliability to ensure that the risk associated with that extension would be acceptable. The results of the recertification should be reviewed by an independent committee, with the purpose of ensuring that NASA has met the intent behind the relevant recommendation of the Columbia Accident Investigation Board.

International Space Station

In considering the future of the International Space Station, the Committee asked two basic questions: What is the outlook between now and 2015? Should the ISS be extended beyond 2015?

The Committee is concerned that the ISS, and particularly its utilization, may be at risk after Shuttle retirement. The ISS was designed, assembled and operated with the capabilities of the Space Shuttle in mind. The present approach to its utilization is based on Shuttle-era experience. After Shuttle retirement, the ISS will rely on a combination of new international vehicles and as-yet-unproven U.S. commercial vehicles for cargo transport. Because the planned commercial resupply capability will be crucial to both ISS operations and utilization, it may be prudent to strengthen the incentives to the commercial providers to meet the schedule milestones.

Now that the ISS is nearly completed and is staffed by a full crew of six, its future success will depend on how well it is used. Up to now, the focus has been on assembling the ISS, and this has come at the expense of exploiting its capabilities. Utilization should have first priority in the years ahead.

The Committee finds that the return on investment from the ISS to both the United States and the international partners would be significantly enhanced by an extension of its life to 2020. It seems unwise to de-orbit the Station after 25 years of planning and assembly and only five years of operational life. A decision not to extend its operation would significantly impair the U.S. ability to develop and lead future international space flight partnerships. Further, the return on investment from the ISS would be significantly increased if it were funded at a level allowing it to achieve its full potential: as the nation’s newest National Laboratory, as an enhanced testbed for technologies and operational techniques that support exploration, and as a management framework that can support expanded international collaboration.

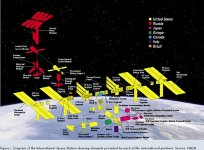

The strong and tested working relationship among international partners is perhaps the most important outcome of the ISS program. The partnership expresses a “first among equals” U.S. leadership style adapted to today’s multi-polar world. That leadership could extend to exploration, as the ISS partners could engage at an early stage if aspects of exploration beyond low-Earth orbit were included in the goals of the partnership agreement. (See Figure i.)

The Constellation Program

The Constellation Program includes the Ares I launch vehicle, capable of launching astronauts to low-Earth orbit; the Ares V heavy-lift launch vehicle, to send astronauts and equipment to the Moon; the Orion capsule, to carry astronauts to low-Earth orbit and beyond; and the Altair lunar lander and lunar surface systems astronauts will need to explore the lunar surface. As the Committee assessed the current status and possible future of the Constellation Program, it reviewed the technical, budgetary, and schedule challenges that the program faces today.

Given the funding upon which it was based, the Constellation Program chose a reasonable architecture for human exploration. However, even when it was announced, its budget depended on funds becoming available from the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2010 and the decommissioning of ISS in early 2016. Since then, as a result of technical and budgetary issues, the development schedules of Ares I and Orion have slipped, and work on Ares V and Altair has been delayed.

Most major vehicle-development programs face technical challenges as a normal part of the process, and Constellation is no exception. While significant, these are engineering problems that the Committee expects can be solved. But these solutions may add to the program’s cost and delay its schedule.

The original 2005 schedule showed Ares I and Orion available to support the ISS in 2012, two years after scheduled Shuttle retirement. The current schedule now shows that date as 2015. An independent assessment of the technical, budgetary and schedule risk to the Constellation Program performed for the Committee indicates that an additional delay of at least two years is likely. This means that Ares I and Orion will not reach the ISS before the Station’s currently planned termination, and the length of the gap in U.S. ability to launch astronauts into space will be at least seven years.

The Committee also examined the design and development of Orion. Many concepts are possible for crew-exploration vehicles, and NASA clearly needs a new spacecraft for travel beyond low-Earth orbit. The Committee found no compelling evidence that the current design will not be acceptable for its wide variety of tasks in the exploration program. However, the Committee is concerned about Orion’s recurring costs. The capsule is considerably larger and more massive than previous capsules (e.g., the Apollo capsule), and there is some indication that a smaller and lighter four-person Orion could reduce operational costs. However, a redesign of this magnitude would likely result in more than a year of additional development time and a significant increase in development cost, so such a redesign should be considered carefully before being implemented.

Capability For Launch To LOW-Earth Orbit And Exploration Beyond

Heavy-Lift Launch to Low -Earth Orbit and Beyond

No one knows the mass or dimensions of the largest hardware that will be required for future exploration missions, but it will likely be significantly larger than 25 metric tons (mt) in launch mass to low-Earth orbit, which is the capability of current launchers. As the size of the launcher increases, the result is fewer launches and less operational complexity in terms of assembly and/or refueling in space. In short, the net availability of launch capability increases. Combined with considerations of launch availability and on-orbit operations, the Committee finds that exploration would benefit from the availability of a heavy-lift vehicle. In addition, heavy-lift would enable the launching of large scientific observatories and more capable deep-space missions. It may also provide benefit in national security applications. The question this raises is: On what system should the next heavy-lift launch vehicle be based?

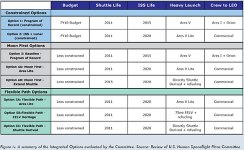

Potential approaches to developing heavy-lift vehicles are based on NASA heritage (Shuttle and Apollo) and (EELV) Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle heritage. (See Figure ii.) Each has distinct advantages and disadvantages. In the Ares-V-plus-Ares-I system planned by the Constellation Program, the Ares I launches the Orion and docks in low-Earth orbit with the Altair lander launched on the Ares V. This configuration has the advantage of projected very high ascent crew safety, but it delays the development of the Ares V heavy-lift vehicle until after the Ares I is developed.

In a different, related architecture, the Orion and Altair are launched on two separate “Lite” versions of the Ares V, providing for more robust mission mass and volume margins. Building a single NASA vehicle could reduce carrying and operations costs and accelerate heavy-lift development. Of these two Ares system alternatives, the Committee finds the Ares V Lite used in the dual mode for lunar missions to be the preferred reference case.

The Shuttle-derived family consists of in-line and side-mount vehicles substantially derived from the Shuttle, thereby providing greater workforce continuity. The development cost of the more Shuttle-derived system would be lower, but it would be less capable than the Ares V family and have higher recurring costs. The lower lift capability could eventually be offset by developing on-orbit refueling.

The EELV-heritage systems have the least lift capacity, requiring almost twice as many launches as the Ares family to attain equal performance. If on-orbit refueling were developed and used, the number of launches could be reduced, but operational complexity would increase. However, the EELV approach would also represent a new way of doing business for NASA, which would have the benefit of potentially lowering development and operational costs. This would come at the expense of ending a substantial portion of the internal NASA capability to develop and operate launchers. It would also require that NASA and the Department of Defense jointly develop the new system.

All of the options would benefit from the development of in-space refueling, and the smaller rockets would benefit most of all. A potential government-guaranteed market to provide fuel in low-Earth orbit would create a strong stimulus to the commercial launch industry.

The Committee cautions against the tradition of designing for ultimate performance at the expense of reliability, operational efficiency, and life-cycle cost.

Crew Access to Low-Earth Orbit

How should U.S. astronauts be transported to low-Earth orbit? There are two basic approaches: a government-operated system and a commercial transport service. The current Constellation Program plan is to use the government-operated Ares I launch vehicle and the Orion crew capsule. However, the Committee found that, because of technical and budget issues, the Ares I schedule no longer supports ISS needs.

Ares I was designed to a high safety standard to provide astronauts with access to low-Earth orbit at lower risk and a considerably higher level of safety than is available today. To achieve this, it uses a high-reliability rocket and a crew capsule with a launch-escape system. But other combinations of high-reliability rockets and capsules with escape systems could also provide that safety. The Committee was unconvinced that enough is known about any of the potential high-reliability launcher-plus-capsule systems to distinguish their levels of safety in a meaningful way.

The United States needs a means of launching astronauts to low -Earth orbit , but it does not necessarily have to be provided by the government. As we move from the complex , reusable Shuttle back to a simpler, smaller capsule , it is appropriate to consider turning this transport service over to the commercial sector. This approach is not without technical and programmatic risks , but it creates the possibility of lower operating costs for the system and potentially accelerates the availability of U.S. access to low-Earth orbit by about a year, to 2 0 1 6. If this option is chosen , the Committee suggests establishing a new competition for this service , in which both large and small companies could participate.

Lowering the cost of space exploration

The cost of exploration is dominated by the costs of launch to low -Earth orbit and of in -space systems. It seems improbable that significant reductions in launch costs will be realized in the short term until launch rates increase substantially —perhaps through expanded commercial activity in space. How can the nation stimulate such activity ? In the 1 9 2 0 s , the federal government awarded a series of guaranteed contracts for carrying airmail , stimulating the growth of the airline industry. The Committee concludes that an exploration architecture employing a similar policy of guaranteed contracts has the potential to stimulate a vigorous and competitive commercial space industry. Such commercial ventures could include the supply of cargo to the ISS (planning for which is already under way by NASA and industry - see Figure iii ) , transport of crew to orbit and transport of fuel to orbit. Establishing these commercial opportunities could increase launch volume and potentially lower costs to NASA and all other launch services customers. This would have the additional benefit of focusing NASA on a more challenging role , permitting it to concentrate its efforts where its inherent capability resides : in developing cutting -edge technologies and concepts , defining programs , and overseeing the development and operation of exploration systems.

In the 1920’s the federal government also supported the growth of air transportation by investing in technology. The Committee strongly believes it is time for NASA to reassume its crucial role of developing new technologies for space. Today, the alternatives available for exploration systems are severely limited because of the lack of a strategic investment in technology development in past decades. NASA now has an opportunity to generate a technology roadmap that aligns with an exploration mission that will last for decades. If appropriately funded, a technology development program would re-engage minds at American universities, in industry, and within NASA. The investments should be designed to increase the capabilities and reduce the costs of future exploration. This will benefit human and robotic exploration, the commercial space community, and other U.S. government users alike.

Future Destinations For Exploration

What is the strategy for exploration beyond low-Earth orbit? Humans could embark on many paths to explore the inner solar system, most particularly the following:

• Mars First, with a Mars landing, perhaps after a brief test of equipment and procedures on the Moon

. • Moon First, with lunar surface exploration focused on developing the capability to explore Mars.

• A Flexible Path to inner solar system locations, such as lunar orbit, Lagrange points, near-Earth objects and the moons of Mars, followed by exploration of the lunar surface and/or Martian surface.

A human landing followed by an extended human presence on Mars stands prominently above all other opportunities for exploration. Mars is unquestionably the most scientifically interesting destination in the inner solar system, with a planetary history much like Earth’s. It possesses resources that can be used for life support and propellants. If humans are ever to live for long periods on another planetary surface, it is likely to be on Mars. But Mars is not an easy place to visit with existing technology and without a substantial investment of resources. The Committee finds that Mars is the ultimate destination for human exploration of the inner solar system, but it is not the best first destination.

What about the Moon first, then Mars? By first exploring the Moon, we could develop the operational skills and technology for landing on, launching from and working on a planetary surface. In the process, we could acquire an understanding of human adaptation to another world that would one day allow us to go to Mars. There are two main strategies for exploring the Moon. Both begin with a few short sorties to various sites to scout the region and validate lunar landing and ascent systems. In one strategy, the next step would be to build a lunar base. Over many missions, a small colony of habitats would be assembled, and explorers would begin to live there for many months, conducting scientific studies and prospecting for resources to use as fuel. In the other strategy, sorties would continue to different sites, spending weeks and then months at each one. More equipment would have to be brought to the lunar surface on each trip, but more diverse sites would be explored and in greater detail

There is a third possible path for human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit, which the Committee calls the Flexible Path. On this path, humans would visit sites never visited before and extend our knowledge of how to operate in space— while traveling greater and greater distances from Earth. Successive missions would visit lunar orbit; the Lagrange points (special points in space that are important sites for scientific observations and the future space transportation infrastructure); and near-Earth objects (asteroids and spent comets that cross the Earth’s path); and orbit around Mars. Most interestingly, humans could rendezvous with a moon of Mars, then coordinate with or control robots on the Martian surface, taking advantage of the relatively short communication times. At least initially, astronauts would not travel into the deep gravity wells of the lunar and Martian surface, deferring the cost of developing human landing and surface systems.

The Flexible Path represents a different type of exploration strategy. We would learn how to live and work in space, to visit small bodies, and to work with robotic probes on the planetary surface. It would provide the public and other stakeholders with a series of interesting “firsts” to keep them engaged and supportive. Most important, because the path is flexible, it would allow for many different options as exploration progresses, including a return to the Moon’s surface or a continuation directly to the surface of Mars.

The Committee finds that both Moon First and Flexible Path are viable exploration strategies. It also finds that they are not necessarily mutually exclusive; before traveling to Mars, we might be well served to both extend our presence in free space and gain experience working on the lunar surface.

Integrated Program Options

The Committee has identified five principal alternatives for the human spaceflight program. They include one baseline case, which the Committee considers to be an executable version of the current program of record, funded to achieve its stated exploration goals, as well as four alternatives. These options and several derivatives are summarized in Figure iv.

The Committee was asked to provide two options that t within the FY 2010 budget pro le. This funding is essentially at or decreasing through 2014, then increases at 1.4 percent per year thereafter, less than the 2.4 percent per year used by the Committee to estimate cost inflation. The first two options are constrained to the existing budget.

Option 1. Program of Record as Assessed by the Committee , Constrained to the FY 2 0 1 0 budget.

This option is the program of record, with only two changes the Committee deems necessary: providing funds for the Shuttle into FY 2011 and including sufficient funds to deorbit the ISS in 2016. When constrained to this budget profile, Ares I and Orion are not available until after the ISS has been de-orbited. The heavy-lift vehicle, Ares V, is not available until the late 2020s, and there are insufficient funds to develop the lunar lander and lunar surface systems until well into the 2030s, if ever.

Option 2. ISS and Lunar Exploration , Constrained to FY 2 0 1 0 Budget.

This option extends the ISS to 2020, and begins a program of lunar exploration using a derivative of Ares V, referred to here as the Ares V Lite. The option assumes completion of the Shuttle manifest in FY 2011, and it includes a technology development program, a program to develop commercial services to transport crew to low-Earth orbit, and funds for enhanced utilization of the ISS. This option does not deliver heavy-lift capability until the late 2020s and does not have funds to develop the systems needed to land on or explore the Moon in the next two decades

The remaining three alternatives t a different budget profile—one that the Committee judged more appropriate for an exploration program designed to carry humans beyond low-Earth orbit. This budget increases to $3 billion above the FY 2010 guidance by FY 2014, then grows with inflation at what the Committee assumes to be 2.4 percent per year.

Option 3. Baseline Case —Implementable Program of Record.

This is an executable version of the Program of Record. It consists of the content and sequence of that program-de-orbiting the ISS in 2016, developing Orion, Ares I and Ares V, and beginning exploration of the Moon using the Altair lander and lunar surface systems. The Committee made only two additions it felt essential: budgeting for the completion of remaining flights on the Shuttle manifest in 2011 and including additional funds for the deorbit of the ISS. The Committee’s assessment is that, under this funding pro le, the option delivers Ares I and Orion in FY 2017, with human lunar return in the mid-2020s.

Option 4. Moon First.

This option preserves the Moon as the first destination for human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit. It also extends the ISS to 2020, funds technology advancement, and uses commercial vehicles to carry crew to low-Earth orbit. There are two significantly different variants to this option. Both develop the Orion, the Altair lander and lunar surface systems as in the Baseline Case.

Variant 4A is the Ares V Lite variant. This option retires the Shuttle in FY 2011 and develops the Ares V Lite heavy-lift launcher for lunar exploration. Variant 4B is the Shuttle extension variant. It offers the only foreseeable way to eliminate the gap in U.S. human-launch capability: by extending the Shuttle to 2015 at a minimum safe-flight rate. It also takes advantage of synergy with the Shuttle by developing a heavy-lift vehicle that is more directly Shuttle-derived than the Ares family of vehicles. Both variants of Option 4 permit human lunar return by the mid-2020s.

Option 5. Flexible Path.

This option follows the Flexible Path as an exploration strategy. It operates the Shuttle into FY 2011, extends the ISS until 2020, funds technology advancement and develops commercial services to transport crew to low-Earth orbit. There are three variants within this option. They all use the Orion crew exploration vehicle, together with new in-space habitats and propulsions systems. The variants differ only in the heavy-lift vehicle used.

Variant 5A is the Ares V Lite variant. It develops the Ares V Lite, the most capable of the heavy-lift vehicles in this option. Variant 5B employs an EELV-heritage commercial heavy-lift launcher and assumes a different (and significantly reduced) role for NASA. It has an advantage of potentially lower operational costs, but requires significant restructuring of NASA. Variant 5C uses a Shuttle-derived, heavy-lift vehicle, taking maximum advantage of existing infrastructure, facilities and production capabilities.

All variants of Option 5 begin exploration along the flexible path in the early 2020s, with lunar fly-bys, visits to Lagrange points and near-Earth objects and Mars y-bys occurring at a rate of about one major event per year, and possible rendezvous with Mars’s moons or human lunar return by the mid- to late-2020s.

The Committee has found two executable options that comply with the FY 2010 budget pro le. However, neither allows for a viable exploration program. In fact, the Committee finds that no plan compatible with the FY 2010 budget pro le permits human exploration to continue in any meaningful way.

The Committee further finds that it is possible to conduct a viable exploration program with a budget rising to about $3 billion annually in real purchasing power above the FY 2010 budget pro le. At this budget level, both the Moon First and the Flexible Path strategies begin human exploration on a reasonable but not aggressive timetable. The Committee believes an exploration program that will be a source of pride for the nation requires resources at such a level.

Organizational And Programmatic Issues

How might NASA organize to explore? The NASA Administrator needs to be given the authority to manage NASA’s resources, including its workforce and facilities. It is noted that even the best-managed human spaceflight programs will encounter developmental problems. Such activities must be adequately funded, including reserves to account for the unforeseen and unforeseeable. Good management is especially dif cult when funds cannot be moved from one human spaceflight budget line to another—and where additional funds can ordinarily be obtained only after a two-year delay (if at all). NASA would become a more effective organization if it were given the flexibility possible under the law to establish and manage its programs.

Finally, significant space achievements require continuity of support over many years. Program changes should be made based on future costs and future benefits and then only for compelling reasons. NASA and its human spaceflight program are in need of stability in both resources and direction. This report of course offers options that represent changes to the present program—along with the pros and cons of those possible changes. It is necessarily left to the decision-maker to determine whether these changes rise to the threshold of “compelling.”

Summary Of Principal Findings

The Committee summarizes its principal findings below. Additional findings are included in the body of the report.

The right mission and the right size: NASA’s budget should match its mission and goals. Further, NASA should be given the ability to shape its organization and infrastructure accordingly, while maintaining facilities deemed to be of national importance.

International partnerships: The U.S. can lead a bold new international effort in the human exploration of space. If international partners are actively engaged, including on the “critical path” to success, there could be substantial benefits to foreign relations and more overall resources could become available to the human spaceflight program.

Short -term Space Shuttle planning: The remaining Shuttle manifest should be own in a safe and prudent manner without undue schedule pressure. This manifest will likely extend operation into the second quarter of FY 2011. It is important to budget for this likelihood.

The human-spaceflight gap: Under current conditions, the gap in U.S. ability to launch astronauts into space will stretch to at least seven years. The Committee did not identify any credible approach employing new capabilities that could shorten the gap to less than six years. The only way to significantly close the gap is to extend the life of the Shuttle Program.

Extending the International Space Station: The return on investment to both the United States and our international partners would be significantly enhanced by an extension of the life of the ISS. A decision not to extend its operation would significantly impair U.S. ability to develop and lead future international space flight partnerships.

Heavy lift: A heavy-lift launch capability to low-Earth orbit, combined with the ability to inject heavy payloads away from the Earth, is beneficial to exploration. It will also be useful to the national security space and scientific communities. The Committee reviewed: the Ares family of launchers; Shuttle-derived vehicles; and launchers derived from the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle family. Each approach has advantages and disadvantages, trading capability, life-cycle costs, maturity, operational complexity and the “way of doing business” within the program and NASA.

Commercial launch of crew to low-Earth orbit: Commercial services to deliver crew to low-Earth orbit are within reach. While this presents some risk, it could provide an earlier capability at lower initial and life-cycle costs than government could achieve. A new competition with adequate incentives to perform this service should be open to all U.S. aerospace companies. This would allow NASA to focus on more challenging roles, including human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit based on the continued development of the current or modified Orion spacecraft.

Technology development for exploration and commercial space: Investment in a well-designed and adequately funded space technology program is critical to enable progress in exploration. Exploration strategies can proceed more readily and economically if the requisite technology has been developed in advance. This investment will also benefit robotic exploration, the U.S. commercial space industry, the academic community and other U.S. government users.

Pathways to Mars: Mars is the ultimate destination for human exploration of the inner solar system; but it is not the best first destination. Visiting the “Moon First” and following the “Flexible Path” are both viable exploration strategies. The two are not necessarily mutually exclusive; before traveling to Mars, we could extend our presence in free space and gain experience working on the lunar surface.

Options for the human spaceflight program: The Committee developed five alternatives for the Human Space flight Program. It found:

• Human exploration beyond low-Earth orbit is not viable under the FY 2010 budget guideline.

• Meaningful human exploration is possible under a less constrained budget, increasing annual expenditures by approximately $3 billion in real purchasing power above the FY 2010 guidance.

• Funding at the increased level would allow either an exploration program to explore the Moon First or one that follows the Flexible Path. Either could produce significant results in a reasonable timeframe.

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|