Report on Progress Toward Security and Stability in Afghanistan

In accordance with sections 1230 and 1231 of the

National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for Fiscal Year 2008

(P.L. 110-181), as amended, and Section 1221 of the

NDAA for Fiscal Year 2012 (P.L. 112-81), and

Sections 1212, 1217, 1223, and 1531(d) of the NDAA for Fiscal

Year 2013 (P.L. 112-239)

Executive Summary1

Afghan security forces are now successfully providing security for their own people, fighting their own battles, and holding the gains made by the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in the last decade. This is a fundamental shift in the course of the conflict. The Afghan National Security Forces (ANSF) have seen their capabilities expand rapidly since 2009, while insurgent territorial influence and kinetic capabilities have remained static. During the 2012 fighting season, ISAF led the fight against the insurgency, helping to put the Government of the Islamic Republic of Afghanistan (GIRoA) firmly in control of all of Afghanistan’s major cities and 34 provincial capitals. During the 2013 fighting season, the ANSF led the fight, and have consolidated GIRoA’s control of Afghanistan’s urban areas. The fact that the ANSF – a force in its infancy five years ago – can now maintain the gains made by a coalition of 50 nations with the best trained and equipped forces in the world is a significant accomplishment.

The ANSF now conduct 95 percent of conventional operations and 98 percent of special operations in Afghanistan. The only unilateral operations that ISAF continues to conduct are ISAF force protection, route clearance, and redeployment. A number of violence indicators are lower in this reporting period than they were during the corresponding period last year, including a six percent drop in enemy initiated attacks (EIAs), a 12 percent drop in security incidents, and a 22 percent drop in improvised explosive device (IED) events.2 However, this success did not come without costs, and the ANSF still face many challenges.

ANSF casualties have increased by 79 percent this reporting period compared to the same period last year, while ISAF casualties have dropped by 59 percent. The insurgency has also consolidated gains in some of the rural areas in which it has traditionally held power. ISAF continues to provide the ANSF with significant advising and enabling support, such as airlift and close air support (CAS). This enabling support will decline through 2014, and will be difficult for the ANSF to fully replace. ANSF capabilities are not yet fully self-sustainable, and considerable effort will be required to make progress permanent. After 2014, ANSF sustainability will be at high risk without continued aid from the international community and continued Coalition force assistance including institutional advising. With assistance, however, the ANSF will remain on a path towards an enduring ability to overmatch the Taliban.

However, military progress alone will not lead to success in Afghanistan. In addition to uncertainties about ANSF sustainability and challenges to security outside of urban areas, challenges with the economy and governance continue to foster uncertainty about long-term prospects for stability. This causes hedging behavior by actors in many sectors, which exacerbates existing instability. Afghanistan has made significant economic progress over the past decade, but it remains one of the poorest countries in the world, and will continue to depend heavily on international aid. The Afghan government is increasingly able to execute parts of its budget and to deliver very basic goods and services. However, the government must continue to work towards reducing corruption and effectively extend governance to many rural areas.

Although problems remain, many of which are detailed in this report, ANSF progress means that the biggest uncertainties facing Afghanistan are no longer primarily military. Assessing whether the gains to date will be sustainable is now more dependent upon the size and structure of the post-2014 U.S. and North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) presence, the Afghan election in 2014, the level of international support provided to Afghanistan after 2014, and whether Afghanistan can put in place the legal and other structures needed to attract investment and promote growth.

ANSF in the Lead

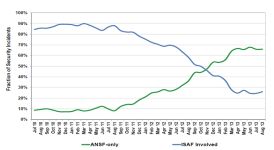

ISAF’s main effort is to assist ANSF development to the point where it can assume full security responsibility for Afghanistan by the end of 2014. Of all lines of effort, this showed the most progress during the reporting period, culminating in the ANSF successfully assuming the lead for security across the country and holding the gains made by ISAF over the past three years. As seen in Figure 1 below, the percentage of security incidents involving only ANSF forces has grown dramatically in the last two years, while the percentage of incidents involving ISAF has correspondingly diminished.

GIRoA and ISAF made a deliberate decision several years ago to focus on rapid ANSF growth, followed by the development of enablers and the professionalization of the force. This decision was made with a full understanding that the ANSF, once built to size, would need to develop the more complex institutional capabilities necessary to make the force self-sustainable. In light of this, ISAF now bases its assistance to the ANSF on the five operational pillars deemed key to long-term sustainability: leadership, command and control (C2), sustainment and logistics, combined arms integration, and training. Improving ANSF capability across these functions is now the main focus of the ANSF development effort. As Afghan capabilities in these areas are still limited, the ANSF continues to require ISAF intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), airlift, resupply, medical, route clearance, and CAS assistance.

The ANSF has nearly doubled in size since 2009. As of August 2013, ANSF force strength has reached 344,602, which is 98 percent of its 352,000 authorized end strength. Including its 24,169 Afghan Local Police (ALP) Guardians, GIRoA had 368,771 uniformed troops and police. Almost all ANSF unit and major equipment fielding will be complete by December 2013. Development of ANSF airpower is more technologically complex, and lags behind the other elements, with some capabilities not fully operational until 2017.

The ANSF will be challenged to close a number of capability gaps in areas where ISAF currently provides support. Afghanistan’s security ministries, despite substantial progress, still require substantive improvements in planning, programming, budgeting, and acquisition. In the fielded force, the Afghan Air Force (AAF), counter-improvised explosive device (C-IED) units, intelligence, fires, medical, and combined arms integration are all areas of focus. Continuing problems with literacy, corruption, leadership, Afghan National Army (ANA) attrition, and manning inhibit ANSF progress. The single most important challenge facing the ANSF, however, is in developing an effective logistics and sustainment system. A lack of trained maintenance technicians and spare parts, and a logistics system that struggles to resupply units in the field, adversely affects every branch of the ANSF.

Despite these challenges, with additional equipment fielding and continued ISAF training and advising, the ANSF are on-track to transition to full sovereign responsibility for security on January 1, 2015. However, beyond 2014, the ANSF will still require substantial Train, Advise and Assist (TAA) mentoring—as well as financial support—to address ongoing shortcomings.

The ANSF has also continued to increase its capability to plan, conduct, and sustain large-scale joint operations. One example was Operation SEMOURGH in Regional Command–East (RCE). This multi-week, large-scale operation involved coordination among all the components of the ANSF from within the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) and Ministry of Defense (MOD) forces to include the AAF and Afghan Special Operations Forces. The ANSF planned and led the operation; Afghan-managed logistics and supply channels supported it. The objectives of the operation were to clear a valley of insurgents and secure a district center so that humanitarian supplies and voter registration materials could be delivered. After three weeks of fighting with insurgents and facing complications due to inclement weather that hampered air and ground movement, the ANSF accomplished its objectives. More importantly, after clearing the valley, the ANSF left behind a police force sufficient to consolidate the operations’ gains and to provide long-term security.

The number of insider attacks against ISAF and coalition forces has declined sharply compared to last year. Thus far, these attacks have not significantly affected the strong relationship between coalition and ANSF personnel, particularly in the field, where they face a common enemy every day. ISAF is cautiously optimistic that the mitigation measures applied over the previous year are working. These measures have reduced, but not eliminated, the inherent threat of insider attacks.

Insurgent Narrative Undermined

The insurgency failed to achieve its stated campaign objectives during the reporting period and its ability to strike at major population centers is under pressure. The enemy is now less popular than in 2012.3 Nonetheless, insurgents maintained influence in many rural areas that serve as platforms to attack urban areas, and were able to carry out attacks with roughly the same frequency as in 2012. The insurgency maintained an operational tempo this year similar to the previous three years, and the geographic distribution of attacks also remained roughly consistent. The insurgency can mount attacks but generally cannot capture or destroy well-defended targets, and are unable to hold significant territory in the face of numerically superior ANSF. While tactically ineffective, these insurgent efforts potentially allow them to reap significant publicity gains. Insurgents continue to seek to conduct high profile attacks (HPAs) against people in population centers as well as against remote outposts to garner media attention, to project an exaggerated image of their capabilities, and to expand perceptions of insecurity.

During the reporting period, sustained counterterrorism (CT) operations exerted pressure on AQ personnel and networks, and eliminated dozens of al Qaeda (AQ) operatives and facilitators, restricting AQ movements to isolated areas within northeastern Afghanistan. ISAF estimates that the number of AQ fighters in Afghanistan remains very low, but the AQ relationship with local Afghan Taliban formations remains intact.

Insurgent groups' main propaganda theme for the past 11 years has been that they are fighting a foreign “occupation.” As the ANSF take over almost all operations and coalition forces transition from a combat to a primarily advisory role, this message increasingly lacks credibility. This is particularly true because insurgent actions continue to cause the vast majority of civilian casualties in Afghanistan, mostly as a result of insurgents’ indiscriminate emplacement of IEDs. Survey data shows an increased belief by the Afghan public that the Taliban is responsible for this rise in civilian casualties.4 As the insurgency finds itself increasingly fighting Afghans—and as even more of the victims of their attacks are fellow Afghans – insurgent propaganda will become less credible. At the same time, a meaningful U.S. enduring presence as part of NATO’s RESOLUTE SUPPORT mission will contradict the insurgent narrative that coalition forces are abandoning Afghanistan.

Transition on Track

On June 18, 2013, ISAF and GIRoA announced Milestone 2013, which marked the ANSF’s assumption of the lead for security across the country. The transition process is on track for completion by the end of 2014, and most districts are making steady progress. Districts in transition pass through several stages that gradually increase the level of Afghan control. Areas that reach the final stage of transition remain at that stage until December 2014 when all provinces and districts in Afghanistan will graduate from transition, regardless of what stage they have achieved. The ANSF has taken the lead in transitioned areas and is helping to expand Afghan governance. This is most apparent in Regional Command–North (RC-N), where ISAF has substantially reduced its coverage.

Transition is a dynamic and uneven process, with some areas progressing quickly and others moving slowly or even regressing. Notably, some areas of Badakshan Province saw increased insurgent attacks, with the ANSF taking significant casualties. In response, the ANSF independently planned and executed several clearing operations in the province, though insurgents were able to use the rugged and remote terrain to avoid getting pinned down, and thus retained the ability to carry out attacks. The fighting in Badakshan was episodic throughout the reporting period.

Improved Cooperation with Pakistan

Pakistan and Afghanistan acknowledge that stability in their respective countries is inter-related. The Afghan insurgency maintains sanctuaries in Pakistan, which is a major factor preventing their decisive defeat in the near term. Furthermore, a significant portion of the materials which perpetuate the conflict emanate from or transit through Pakistan. Relations between the two nations began to improve in September when President Karzai visited Prime Minister Sharif. Additionally, the military-to-military relationship between the nations improved incrementally; senior Pakistani, Afghan, and ISAF leaders took part in tripartite discussions, with similar meetings held at lower levels. Tactical level military-to-military coordination continues to be problematic without a politically endorsed, diplomatically supported bilateral border management strategy. As a result, cooperation along the border remains uneven. Some Pakistani insurgents have fled into Afghanistan and then staged attacks into Pakistan. Pakistan has conducted counterinsurgency operations against Pakistan-focused militants located along the border with Afghanistan, which in some cases have restricted the operating space and resources of Afghan-focused insurgents. Pakistan has made clear that it supports an Afghan-led reconciliation process.

The United States and other coalition nations increased the transport of materiel into and out of Afghanistan through the Pakistan ground lines of communication (GLOCs), greatly reducing transportation time and cost. As of the end of the reporting period, Pakistani GLOCs were capable of handling the vast majority of the cargo headed into and out of Afghanistan.

U.S. – Afghan Relations

As agreed in the Strategic Partnership Agreement (SPA) signed by Presidents Obama and Karzai in May 2012, the United States and Afghanistan are negotiating a Bilateral Security Agreement (BSA). The BSA would supersede the 2003 Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) with Afghanistan and provide the legal framework for the presence of U.S. forces in Afghanistan after 2014. The BSA would also set parameters for future defense cooperation activities between the two countries, confirm and codify this enduring defense partnership, and send a clear message that the United States will not abandon Afghanistan. The BSA will be concluded as an executive agreement, not a mutual defense treaty.

BSA negotiations began in November 2012, with a goal to conclude within one year. The BSA text is now largely complete and negotiations have moved to Kabul for policy level decisions and conclusion. The BSA, if concluded, would enter into force on January 1, 2015. The BSA will serve as a blueprint for the NATO-Afghanistan SOFA. Following completion of the BSA, NATO working groups would negotiate a new SOFA with Afghanistan for the NATO post-2014 RESOLUTE SUPPORT mission.

On June 18, 2013, the Taliban opened a political office in Doha, Qatar, to facilitate peace talks with the GIRoA. At the official opening ceremony, widely covered by the media, the Taliban displayed a flag and name plaque identifying them as the “Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan,” the same name taken by the Taliban government that ruled Afghanistan until 2001. Qatari authorities clarified that the name of the office was the “Political Office of the Afghan Taliban” and removed the flag and plaque; the office was subsequently closed. On June 19, 2013, President Karzai suspended BSA negotiations with the United States, but they have since resumed.

Afghan Governance and Development Challenges Continue

Effective governance, rule of law, and sustainable economic development are all necessary for long-term stability in Afghanistan. However, these are hindered by multiple factors, including widespread corruption, limited formal education and skills, illiteracy, minimal access by officials to rural areas, lack of coordination between the central government and the Afghan provinces and districts, and uneven distribution of power among the branches of the Afghan government.

GIRoA capacity to provide stable, representative, transparent, and responsive governance for the citizens of Afghanistan continues to develop, although progress is slow and uneven. Revenue generation, including tax collection at the municipal level, has improved in recent years, but has decreased this year compared to the last. Additionally, execution of the development budget remains a concern.

The Afghan government is highly centralized, with revenue, budgeting, spending, and service delivery authority residing with the central ministries in Kabul. This level of centralization limits the efficiency of service delivery at the provincial and district levels. Development of capacity at local levels is slowed by limited human capital as well as by delays in enactment of structural reforms by the central government. There are some parts of the government that do have relatively effective service delivery, such as the Ministry of Public Health and the Ministry of Rural Rehabilitation and Development.

The July 2012 Tokyo Conference recognized many of these issues, and the resulting Tokyo Mutual Accountability Framework (TMAF) included explicit commitments by the Afghans to address some of the major weaknesses in sub-national governance. Some progress was made in meeting TMAF commitments during the reporting period: adoption of electoral legislation, implementation of an Independent Election Commission (IEC) voter registration plan, and drafting of the Independent Election Commission operational plan. Budget transparency increased, and World Trade Organization (WTO) accession is on track. To enhance accountability for Tokyo deliverables, the U.S. government announced in July an incentive program that set aside $175 million in planned funding over two fiscal years, to be released when adequate progress is made on benchmarks agreed with GIRoA in the TMAF, including points on elections, anti-corruption, women’s rights, and revenue generation.

Economic growth and development in Afghanistan will continue to be led through 2014 by investments in construction and by private consumption driven largely by donor contributions and ISAF spending. The ongoing reduction of ISAF personnel is likely to have a negative effect on economic growth. Donor funding commitments made in Tokyo provided an important signal from the international community that there will be continued funding after 2014 to support the Afghan economy and mitigate the effects of transition, particularly because the economy does not yet have a basis for sustained growth. The non-opium agricultural sector comprises about 20 percent of total gross domestic product (GDP), and about 80 percent of the work force is involved in agriculture. Opium production, however, remains a substantial portion of overall agriculture output and will continue to fuel corruption and fund the insurgency. Mining accounts for a marginal share of GDP but has the potential to expand if the government implements pending legislation to modernize the rules and regulations governing this sector. The information technology sector, particularly telecommunications, is one area of Afghanistan’s economy that is showing continued growth.

Sustaining governance, development, and security gains beyond 2014 will depend in large part upon a successful presidential election, a smooth transfer of power, and the political will to tackle needed reforms. The Afghan government committed in the U.S.-Afghan SPA and the TMAF to promote free, fair, inclusive, and transparent elections. U.S. assistance is designed to help the Afghans meet that goal. The U.S. government has provided substantial support for election reform and preparations including technical advice and funding for Afghanistan’s independent election institutions and capacity building for civil society.

Challenges in governance and sustainable economic development continue to slow the reinforcement and consolidation of security gains. Ongoing insurgent activity and influence in some parts of the country continue to inhibit economic development and improvements in governance. Unqualified and corrupt political officials in parts of the central government undermine government efficacy and credibility, threatening the long-term stability of Afghanistan. During the reporting period, the Afghan government's counter-corruption efforts have shown no substantial progress, apart from the public acknowledgement that large-scale corruption exists.

Despite these challenges, the Afghan population continues to benefit from the vast improvements in social development made over the past decade, particularly in health and education. In the past decade, Afghanistan has made the largest percentage gain of any country in the world in basic health and development indicators. In 2000, Afghanistan had 1.2 million students enrolled in school, whereas now it has over 10 million. In 2000, male life expectancy was 37 years, whereas now it is 56. In 2000, fewer than five percent of Afghans had cellular phones, whereas now in excess of 60 percent do, including 48 percent of women. Cell service coverage has now expanded by 80 percent. Few but the privileged had internet connectivity in 2000, whereas now an estimated that 65 percent of the population has access to internet connections. In 2000, Afghanistan had only two international airlines servicing Kabul; now there are 12 international airlines servicing most of Afghanistan’s major cities.

In the 1990s, Taliban ideology and control depended, in part, upon the low education level and isolation of poor Afghans. The rapid progress of the last decade has altered Afghan society and made Afghans richer, less isolated, and better educated. The old Afghanistan—which the Taliban claim to represent and hope to rule— is rapidly disappearing.

1This report is submitted consistent with section 1230 of the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2008 (Public Law 110-181), as

amended. It includes a description of the comprehensive strategy of the United States for security and stability in Afghanistan This report is the

eleventh in a series of reports required every 180 days through fiscal year 2014 and has been prepared in coordination with the Secretary of State,

the Office of Management and Budget, the Director of National Intelligence, the Attorney General, the Administrator of the Drug Enforcement

Administration, the Administrator of the U.S. Agency for International Development, the Secretary of the Treasury, and the Secretary of

Agriculture. This assessment complements other reports and information about Afghanistan provided to Congress; however, it is not intended as

a single source of all information about the combined efforts or the future strategy of the United States, its coalition partners, or Afghanistan. The

information contained in this report reflects information through September 30, 2013. This is a historical document that covers progress in

Afghanistan from April 1, 2013, to September 30, 2013, although some more recent updates of key events are included. The next report

will include an analysis of progress toward security and stability from October 1, 2013, to March 31, 2014.

2 These figures compare data from April 1, 2013 through September 15, 2013 with data from April 1, 2012 through September 15, 2012.

3 Results from the ISAF Joint Command BINNA survey wave #14 (July/August 2013).

4 Results from the ISAF FOGHORN survey data wave 16 (Aug 2013).

Access Full November 2013 Report on Progress Toward Security and Stability in Afghanistan [PDF 5.57MB]

|

NEWSLETTER

|

| Join the GlobalSecurity.org mailing list |

|

|

|