Learn

From origins as an unnamed Biblical figure to incarnations as an iconic seductress, the character of Salomé has captivated artists, playwrights, and poets for more than two millennia. A multidisciplinary project this fall brought together scholars and performers from a wide range of disciplines to explore the story. “The Veils of Salomé,” part of this year’s Humanities Project, was organized by Emil Homerin, professor of religion, and Matthew Brown, professor of music theory at the Eastman School.

12th century: Salomé dancing, capital of Santiago de Agüero Church, Spain (Photo: iStockphoto)

12th century: Salomé dancing, capital of Santiago de Agüero Church, Spain (Photo: iStockphoto)Circa 20 to 30 CE

Jewish historian Josephus identifies Salomé as a daughter of Herod Antipas and his second wife, Herodias, but doesn’t indicate that she was complicit in John the Baptist’s execution.

Although she’s not mentioned by name in the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, Christian tradition identifies her as one of the women who danced for Herod and Herodias at a birthday celebration for Herod. When offered a prize for her dancing, the daughter asks that John the Baptist be executed. The New Testament stories imply that the girl’s mother suggested the execution because John had preached against Herod’s divorce from his first wife and his marriage to Herodias. Christian tradition would later identify Salomé as the dancer who asked for John the Baptist’s head.

1610: Salomé Receives the Head of Saint John the Baptist, Caravaggio. (Photo: © National Gallery, London/Art Resource, NY)

1610: Salomé Receives the Head of Saint John the Baptist, Caravaggio. (Photo: © National Gallery, London/Art Resource, NY)Circa 1500

The story of Salomé takes on new life in the arts of the early Renaissance, where painters such as Titian, Caravaggio, Botticelli, and others depict her in scenes from Herod’s court. She comes to represent the world of the flesh while John the Baptist represents the life of the spirit.

1877

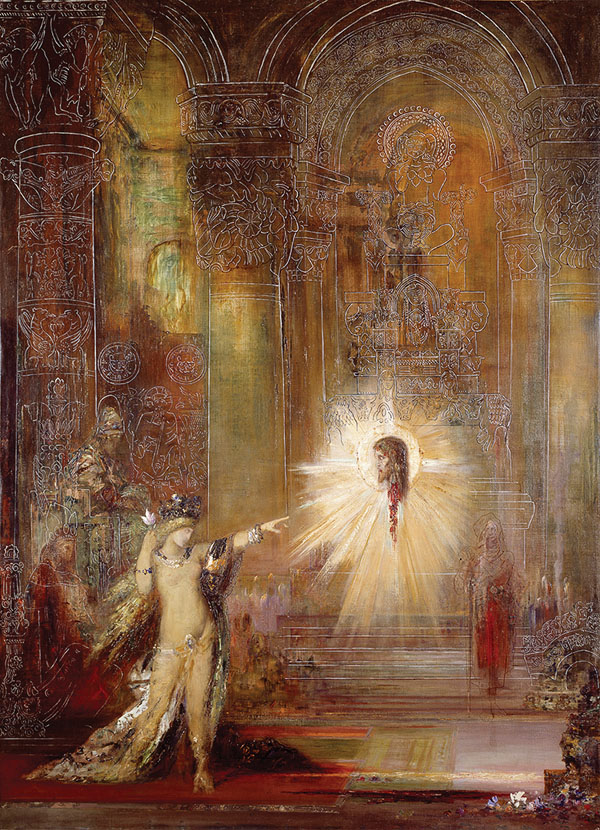

1876: The Apparition or Dance of Salomé, Gustave Moreau (detail) (Photo: Corbis)

1876: The Apparition or Dance of Salomé, Gustave Moreau (detail) (Photo: Corbis)In his story “Herodias,” the French writer Gustave Flaubert depicts Herodias as the driver of the story of John the Baptist’s execution. The story becomes the basis for Jules Massenet’s 1881 opera, Hérodiade.

1896

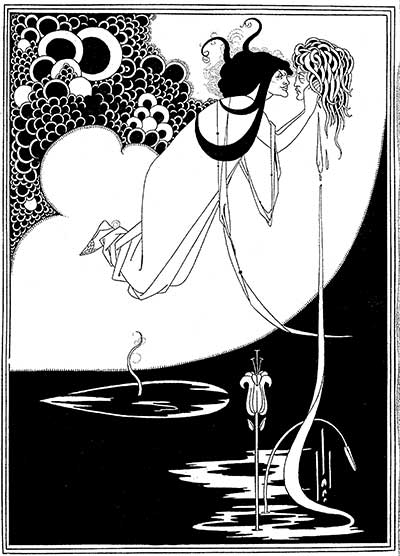

1893: Illustration for Oscar Wilde’s Salomé, Aubrey Vincent Beardsley. (Photo: Corbis)

1893: Illustration for Oscar Wilde’s Salomé, Aubrey Vincent Beardsley. (Photo: Corbis)Writing in French because British laws prohibited the depiction of Biblical figures, Oscar Wilde writes the play Salomé. Familiar with Flaubert’s story as well as earlier versions of the story by the writer Heinrich Heine, the painter Gustave Moreau, and other literary and visual artists, Wilde depicts Salomé as a seductive manipulator who steps out of the shadow of Herod and Herodias to become the protagonist of the Biblical story. Wilde introduces “The Dance of the Seven Veils” as the iconic erotic dance attributed to Salomé.

1905

1905: Soprano Mary Garden as Salomé in Richard Strauss’s opera. (Photo: Corbis)

1905: Soprano Mary Garden as Salomé in Richard Strauss’s opera. (Photo: Corbis)Salomé, an opera by German composer Richard Strauss premieres. Based on the Wilde play, the opera shocked many early audiences with its climatic depiction of Salomé, who during “The Dance of the Seven Veils” declares her love for John the Baptist and—true to Wilde’s play—kisses his severed head.

1986

1986: Salomé, P. Craig Russell. (Photo: Courtesy of P. Craig Russell)

1986: Salomé, P. Craig Russell. (Photo: Courtesy of P. Craig Russell)Drawing on both the Wilde play and the Strauss opera, noted graphic novelist P. Craig Russell writes “Salomé,” as part of his “Opera Variation, Vol. 3.”

2014

Table Top Opera, a chamber ensemble of Eastman School faculty, alumni, and friends, performs “Salomé,” an adaptation of Russell’s graphic novel with a reworked instrumental rendition of the Strauss opera. The production replaced singers and a symphony orchestra with a mixed ensemble of jazz and classical instruments and a newly choreographed version of “The Dance of the Seven Veils.”

—Kathleen McGarvey