There are many ways to show the unknown.

Some science fiction illustrations stand out in their depiction of action; some through portrayal of the landscapes of alien worlds; some by imagining technology of the future (or the past, as the case may be); some by presenting aliens in a myriad of variations; some, in capturing the appearance of a tale’s protagonists – male and female; young and old – in the context of adventure, danger, discovery, fear, failure, and (one would hope) triumph

But, science fiction art (and not just the art of science fiction) need not be “literal” in terms of adhering to a story’s original text to have an impact. Likewise, an illustration that’s largely symbolic and heavily stylized can be more visually arresting than an image literal. In this regard, the work of Richard Powers immediately comes to mind. (Well, there are lots of examples of his work at this blog!)

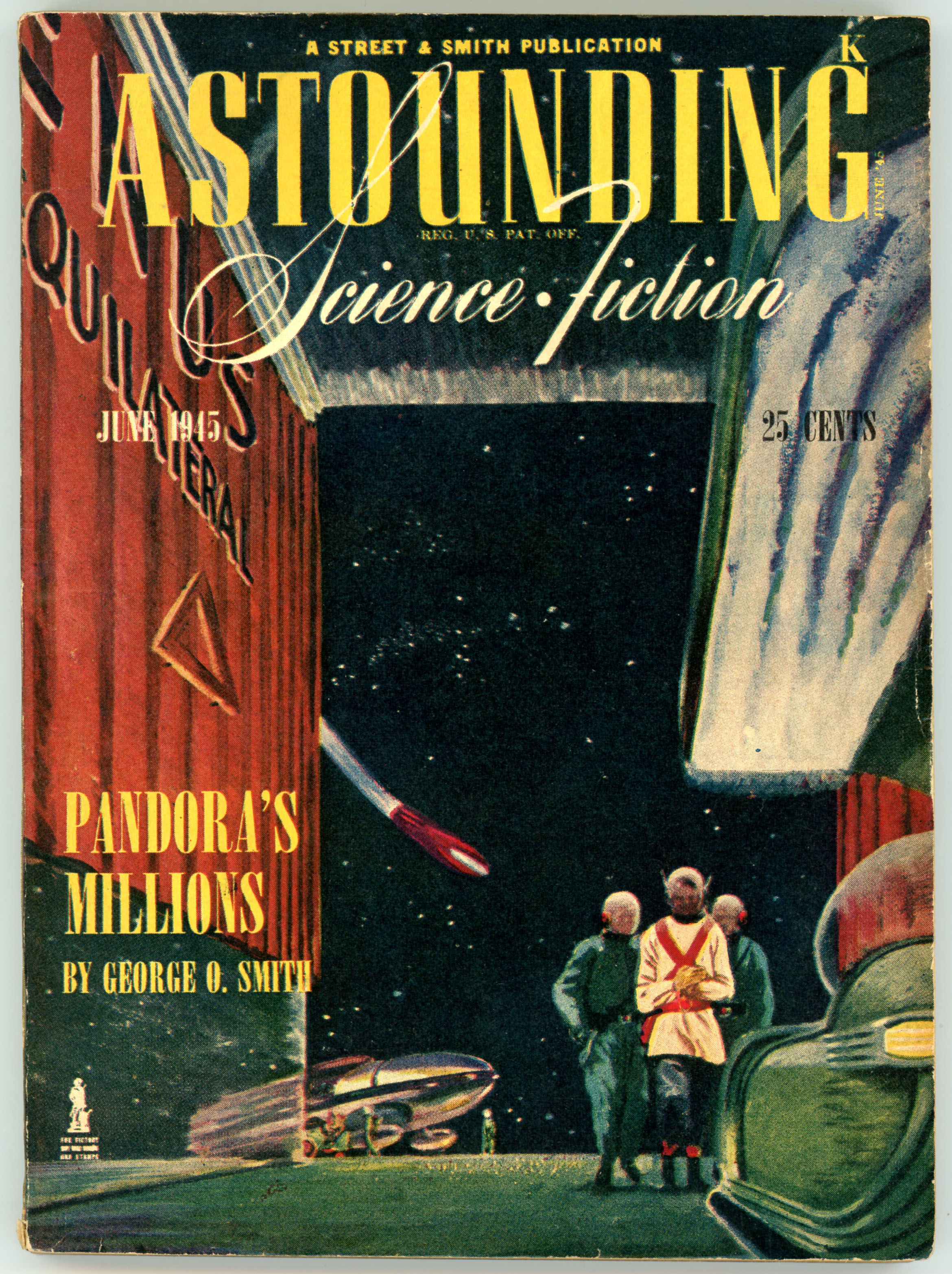

Though his body of work was, stylistically, vastly different from that of Powers, Hubert Rogers, who created many covers, and many, many (very many, come to think of it…) interior illustrations for Astounding Science Fiction from February of 1939 through May of 1952, created art that – while not purely imaginative and fanciful – was often striking in its use of story elements and plot elements as symbols. (His interior art, far more so.)

His superb cover for the November, 1949 issue of Astounding being a case in point.

Created for the second of the four installments by Isaac Asimov that, collectively, would eventually comprise and be published as Second Foundation, the cover “illustrates” part one (of three) for “And Now You Don’t”.

The cover doesn’t really depict any specific scene or event from the tale. Instead, it shows and symbolizes the story’s characters.

There’s the startled looking face of Arkady Darell in the lower right corner. To her left, ill-defined in murky shades of green: the Mule. While I’m not certain about the identity of the figure in red behind Arkady, I’m inclined to think that he’s Homer Munn: A librarian who is among a group of conspirators attempting to locate the Second Foundation, upon whose spaceship Arkady stows away during Munn’s efforts to find such information at the Mule’s palace.

Well, those are the elements. But the way that Rogers arranged them is really creative. First, rather than a simple scene in space, there’s a plain, bold, bright, yellow background. Against that, a bluish-gray, fog-like shadow extends across the scene, lending an air of concealment and murkiness. And finally (well, Homer Munn is a librarian, after all) an array of alpha-numeric symbols extends across the scene through a pair of red arrows, which perhaps symbolize a 1949 version of an automated text reader. Coincidentally, there’s something very “Turing machine reader”-ish in the appearance of this string of characters.

Seemingly juxtaposed at random, together, everything really works. The yellow, blue, red, and green “fit” together perfectly, and, and the figures and faces balance each other as well.

A superb job on Rogers’ part. Well, some of his work is truly stunning, and, I think, as good as if not actually better than that some of his better known near-contemporaries, one of whom received vastly greater accolades. Overall, the central, consistent, and most distinguishing quality of Roger’s work – especially his black and white interior illustrations – is its deeply mythic, rather than literal, air.

Oh, yes…. The issue’s cover (a nearly-hot-off-the-press-looking copy; the colors have held up beautifully across seven decades) appears below, followed by Michael Whelan’s 1986 beautifully done depiction of Arkady Darell on Trantor, which appeared as the cover of the 1986 edition of Second Foundation.

Arkady Darell amidst the ruins of Trantor, as depicted by artist Michael Whelan for the cover of the Del Rey / Ballantine 1986 edition of Second Foundation.

Arkady Darell amidst the ruins of Trantor, as depicted by artist Michael Whelan for the cover of the Del Rey / Ballantine 1986 edition of Second Foundation.

You can view another Astounding Science Fiction cover – for the magazine’s December, 1945 issue, wherein appeared Part I of “The Mule” – here.

________________________________________

The novellas that comprise the Foundation Trilogy are listed below:

Foundation

These four novellas form the first novel of the Foundation Trilogy (appropriately entitled Foundation), which was published by Gnome Press in 1951. However, the first section of Foundation, entitled “The Psychohistorians”, is unique to the book itself, and as such did not appear in Astounding.

May, 1942 – “Foundation” (in book form as “The Encyclopedists”)

June, 1942 – “Bridle and Saddle” (in book form as “The Mayors”)

August, 1944 – “The Big and The Little” (in book form as “The Merchant Princes”)

October, 1944 – “The Wedge” (in book form as “The Traders”)

________________________________________

Foundation and Empire

Foundation and Empire – the second novel of the Foundation Series, first published in 1952 by Gnome Press, is comprised of “Dead Hand” (retitled “The General”) and “The Mule” (which retained its original title).

April, 1945 – “Dead Hand” (in book form as “The General”)

November, 1945, and, December, 1945 – “The Mule”

_______________________________________

Second Foundation

Second Foundation – the third novel of the Foundation series, first published by Gnome Press in 1953 – is comprised of the novellas “Search By the Mule”, and, “Search By the Foundation”. The former was published in the January, 1948 issue of Astounding Science Fiction under the title “Now You See It…”, while the latter appeared as three parts in Astounding: in the magazine’s 1949 issues for November and December, and, the January, 1950 issue.

January, 1948 – “Now You See It…” (in book form as “Search By the Mule”)

November, 1949, December 1949, and, January 1950 – “…And Now You Don’t” (in book form as “Search By the Foundation”)

________________________________________

Of the eleven issues of Astounding listed above, six were published with cover art symbolizing or representing the actual Foundation story within that particular issue. But, the cover art for issues of May, 1942; October, 1944; December, 1945; December, 1949, and January, 1950 was entirely unrelated to Asimov’s trilogy.

A Bunch of References

“…And Now You Don’t”, at Internet Speculative Fiction Database

Arkady Darell, at Asimov Fandom

Arkady Darell, at Info Galactic

Foundation Series, at Wikipedia

Foundation, at Wikipedia

Foundation and Empire, at Wikipedia

Second Foundation, at Wikipedia

Guide to Wild American Pulp Artists – Hubert Rogers, at Pulp Artists

List of Foundation Series Characters, at Wikipedia

Short Reviews – …And Now You Don’t (Part 1 of 3), by Isaac Asimov, at Castalia House

The Course of Trantor: Covers from Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy (art by Michael Whelan), at reddit.com (r/pics)

Turing Machine, at Wikipedia

Turing Machine Operation, at University of Cambridge Department of Computer Science and Technology

A Turing Machine – Overview (video of home-made Turing Machine in operation), at Mike Davey’s YouTube channel