The Ancient Maya

From humble beginnings in the Yucatan, the Maya rose to dominance across what is now Central America and southern Mexico, spreading their knowledge of science, architecture, and survival far and wide. The Maya are famous for many things, among them advanced farming techniques, writing in hieroglyphs, superior knowledge of astronomy and the passage of time, creators of sturdy art, and a war-based ball game that has echoes down through the centuries. It was the Olmecs who established the first true civilization in Central America, beginning in 1500 B.C. The Maya were not far behind, however, and the timing of the Maya's rise to prominence and the final decline of the Olmecs could very well not be a coincidence.

Maya settlements began about 1800 B.C. in what is now Belize, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, and Mexico. Three distinct areas evolved: the Northern Lowlands on the Yucatan Peninsula, the Southern Lowlands in the Petén district of what is now northern Guatemala and an area of what is now Mexico, and the Southern Highlands, in the mountains of what is now Guatemala. As with many other civilizations, the earliest Mayan settlements were farming ones, with crops that included beans, cassava (used to make flour and tapioca), chilies, corn, and quash. They also were one of the first to consume chocolate, in the form of a hot drink.

Maya soon moved on to building pyramids, plaza, and temples and carving images into stone monuments. Through the years, archaeologists have uncovered in Maya ruins evidence of sophisticated urban planning. Settlements became cities, with populations ranging from 5,000 to 50,000. Major cities included Bonampak, Calakmul, Chichén Itza, Copán, Dol Pilas, Mirador, Palenque, Río Bec, Tikal (the capital), Uaxactún, and Uxmal. Trade between these cities was common. Rivalries betwen cities was common and, at times, violent. Weapons used included bow and arrow, the blowgun, and the atlatl, a long stick with a notched end that held a dart or javelin; a warrior who used an atlatl could achieve much deadlier accuracy and range than using only his body.

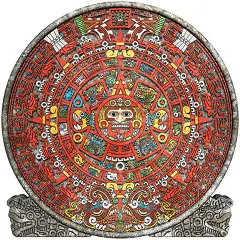

Maya believed strongly in science, as evidenced by their attention to irrigation and terrace farming, both of which would have provided much-needed agricultural versatility in the jungles of the area. They were, for their time, advanced in mathematics and astronomy, making liberal use of zero in their calculations (long before other civilizations were doing so), designing pyramids and other structures to facilitate astronomical observations (such as a solstice), and creating a complex calendar system based on 365 days that stretched back far before their civilization began and then well into the future. And yet, in a historical oddity, Maya never used the wheel or made much use of draft animals; in fact, they had very few domesticated animals. Those wanting to travel or transport something went by foot or in a canoe. Maya had strong religious beliefs, worshiping many gods, primarily nature-related ones. Holy elites acted as adjuncts to the high king, who served as intermediary between the common people and the gods. Elaborate religious ceremonies were commonplace. Some of these ceremonies involved human sacrifice. Chocolate, in the form of toasted cacao seeds, was sometimes used in religious ceremonies. One such ceremony combined religion and athletics. This was the Mayan Ball Game, which pitted two teams of competitors against each other, attempting to throw a rubber ball through a very high hoop. At the end of the game, the members of one team would be sacrificed to the gods, as a tribute. (Whether that was the losing or the winning team continues to divide historians.) Maya spoke many languages and wrote using hieroglyphs, creating the only known fully developed writing system in either American continent before the arrival of Europeans. Deciphering of this hieroglyphic system long puzzled historians. By the end of hte 20th Century, linguistic experts had deciphered nearly all of the Mayan system. Maya wrote in codices (books) made of paper, which in turn was made from tree bark. Four of these codices are known to survive. Examples of Mayan art survive, among them mural paintings and sculpture; stucco masks were of particular interest to Mayan artists.

By A.D. 900, Mayan civilization had suffered a dramatic decline. Cities had been abandoned in large numbers. Historians have several theories for this decline:

A few highland cities carried on, among them Chichén Itza. Spanish explorers in the 16th Century found a much diminished Maya civilization, returned to its roots, with its great cities overtaken by the jungle. Spain conquered the last known Maya city, Nojpetén, in 1697. Maya traditions continued in small communities and exist to this day. |

|

Social Studies for Kids

copyright 2002–2024

David White