What I've learned about motor impairment

Accessibility is (thankfully) receiving a fair amount of attention in web development circles these days. As designers and developers we should all be seeking to create experiences that are as inclusive as possible. With that in mind I’d like to talk about designing for motor impairments, an aspect of accessibility that I think is often overlooked.

The National Center for Health Statistics reported in 2015 that 32% of Americans aged 18 and over have some type of motor impairment. That number may seem quite large, but it covers a wide range of disabilities and limitations. Often when we discuss motor function related disabilities we limit the discussion to those with severe impairments such as paralysis or cerebral palsy. The reality is that almost any decreased motor function control can negatively impact someone’s ability to browse the web or use your application. In fact, the likelihood that you will face some type of motor impairment in your lifetime is quite high. Whether it’s temporary like a broken wrist, or a permanent loss due to things like illness or the natural process of aging it’s an issue that almost everyone will have to deal with at some point. So naturally it makes sense to design your projects with these limitations in mind.

My own experience with motor impairment began in 2012 when I first noticed a weakness in my right hand. I chalked it up to all day coding sessions and perhaps a mild case of carpal tunnel. Wearing a brace and resting the hand didn’t help however, and by 2013 I was seeing actual muscle wasting in my hand. This led to several months of extensive testing and an eventual diagnosis of ALS. Due to the nature of ALS my control over most motor functions has experienced a gradual but steady decline. This means that as my motor functionality has lessened I’ve had to adapt to remain productive. Currently I’ve lost almost all function in my right hand and my left hand is significantly affected. My fine motor control is almost completely gone with only my index finger and thumb on my left hand still relatively active. Adapting to these diminished capabilities has taught me a lot about how websites and apps can better address the needs of those with a wide range of motor impairments. I’d like to share what I’ve learned.

Don’t assume keyboard access is all you need

Most of the articles I’ve read about accessibility and motor impairments list the types of assistive technology designed to help those individuals access the web and then advise you to make your site keyboard accessible in order to accommodate them. Making your site keyboard accessible is a good idea for multiple reasons, but I have found that as my impairment has progressed I use my keyboard less and less frequently. My primary means of interacting with the web is by using my mouse, over which I still have a fair amount of control, and through voice dictation software. Voice dictation is, shall we say, less than perfect. If you ever want to assuage your fears of a world dominated by AI simply spend a few hours trying to dictate an email. Filling out forms and typing any kind of input that has precise values and special characters can be frustrating and time consuming. When designing interactions that require input from the user try to keep in mind that not everyone has total control over their keyboard and limit unnecessary inputs. Forms especially should be designed with these types of users in mind and should assist in filling out the form when possible. Here are some things that I find extremely helpful:

Auto complete/Autofill

There are times when I don’t feel like launching my voice dictation software to do a simple search or fill out a small form. In those cases I typically do the one finger hunt and peck on my keyboard or use my mouse to interact with an on-screen keyboard. Auto completion can save me a tremendous amount of time and frustration in those instances. The good news is there is a fair amount of open source auto completion libraries that are fairly easy to integrate into your sites. Twitter’s typeahead.js is a popular choice and offers a fairly robust solution.

Having forms that auto fill standard information is also incredibly helpful to those of us with motor impairments. There are security concerns and usage patterns that you must take into account when deciding whether or not to enable auto fill but in my opinion the benefits outweigh the concerns in most cases. If you are not familiar with it check out this Google Developers introductory article on the subject and then read this fantastic article by Jason Grigsby that goes into more detail and explains usage patterns.

Show me my password

Perhaps the most frustrating input issue for me is not being able to see my password as I type. Whether I’m using voice dictation or a single finger on my keyboard precise input is extremely difficult. This difficulty is increased when you introduce special characters and many of the requirements found in passwords. Not being able to see what I’ve input equates to a high degree of failure when entering passwords. Yes, password managers do help and I’m not above copying and pasting into the input field but I really shouldn’t have to. Dave Rupert recently tweeted this animation of the password field in Microsoft Edge that has the option baked into it. Until this pattern becomes standard in every browser it’s up to you to make sure users have the option of displaying their password.

Allow for fine motor control issues

Many of the sites and applications that I use assume that everyone has the same amount of control over their mouse as everyone else. While I still have a fair amount of control I’m certainly not as precise as I used to be. It’s worth pointing out as well that the mouse isn’t the only form of input that people use. Larger trackpads, switch controls, and other devices are often used in place of a mouse. The traditional line of thinking that complex, precise interactions are okay as long as they are also accessible via the keyboard is incorrect. There are a lot of capabilities that fall in between keyboard access and fine motor control over the mouse that you should plan for. Here are just a few of the issues I regularly deal with:

Don’t autoplay videos

There are so, so many reasons not to autoplay video, but I’m happy to add one more. Like most people I often browse several tabs at a time. Clicking through them to stop the myriad of videos that inevitably load and play is time-consuming and tiring. In the rare case that I actually did want to watch the video my inability to quickly maneuver on the page means I have to stop the video and back it up in order to watch it all. This also means that I have to watch whatever ad content is tacked onto it twice. I know these decisions are generally driven by marketing people but let’s make an effort, shall we?

Avoid hover-only controls

Whether it’s navigation, tool tips, or widget settings interacting with hover-based controls can be extremely frustrating. It’s easy for people like me to wander outside the hover area while trying to make a selection and have to start the entire process over again. It’s even worse when those controls are programmed with a timeout option that removes the dialog after a specific amount of time. For people that use inputs like switch controls it makes it extremely difficult for them to complete the task in the allotted time. I’m a huge fan of how Codepen handles their controls. Any control that is accessed via a hover interaction either remains on the screen until the user clicks focus away from it or introduces a modal window that makes it much easier for the user to complete their task.

This is especially important for navigation. When creating drop-down menus or complex menu interactions carefully consider the amount of distance you are asking the user to travel and the hit target required by the menu. Allowing any drop-down content to remain visible until focus has been moved away from the menu creates a much more accessible navigation pattern. To show you what I mean I recorded a video of me interacting with the Sasquatch Music Festival site. I’ve attended this festival multiple times and love it dearly, but in this case notice how difficult it is for me to access their FAQ page. This was actually my most successful attempt, the hover-only controls mixed with a small hit area and a large travel distance makes this menu very difficult to use for anyone with fine motor control issues.

Infinite scrolling considerations

Aside from the oft-mentioned usability concerns, infinite scrolling can be problematic for people with limited motor functionality. For sites with active timelines like Twitter and Facebook the use of infinite scrolling makes sense. However I’ve encountered instances of infinite scrolling that could have easily split content into multiple pages or offer alternate ways to find and consume content. Long periods of scrolling can be tiring, especially if I’m using the scroll wheel for extended periods of time. My imprecise use of the mouse usually creates problems when new content is loaded. Instead of seamlessly loading the next block of content I tend to jump past newly loaded content forcing me to scroll back up to find the point I left off. In some cases I become so frustrated I stop looking for content and leave the site. Make sure that if infinite scrolling is implemented on your site that your scrolling is smooth and content loading is unobtrusive and seamless. In a perfect world you can give the user a choice between infinite scrolling, pagination, or other ways to discover content.

Be mindful of touch

Touchscreens have often been touted as easier to use for people with motor control issues. There certainly are some tasks that are easier for me to perform on my phone than on my laptop. Most mobile devices have integrated accessibility controls that give people with disabilities additional options not typically found on personal computers. You shouldn’t assume however that touch is intrinsically better when dealing with mild to medium level motor impairments. Here are some issues to consider when designing for touch:

Avoid small hit targets

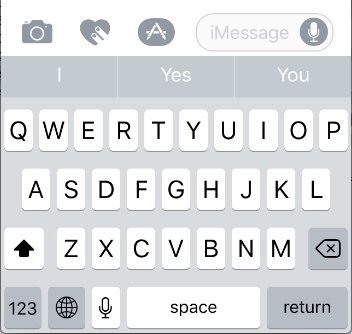

Apple actually did a pretty good job of educating people about the importance of larger hit areas. Dubbed the “fat fingers” rule we were told to make our hit targets a minimum of 44px x 44px. As phone sizes have gotten larger and the viewport easier to control that seems to have gone out the window. Take for example Apple’s default messenger application. Because of the larger screen sizes of the iPhone 6 and 7, they have crammed more and more items into the keyboard and controls. Since I’m still using an iPhone 5 the screen real estate is not large enough to comfortably hold all of the inputs. It’s much easier for me now to dictate text messages rather than type them, but the reduced size of the icons and my less than stellar fine motor control usually results in me unintentionally switching keyboards five or six times or hitting the spacebar several times before finally triggering dictation. Equally problematic is the input field for the text message itself. So little screen real estate remains that instead of merely triggering a text I end up selecting insert media or any of the other myriad options rather then a simple text message. When designing hit targets make sure you not only have a large enough hit area but there is enough negative space around it to avoid unwanted selections. Remember it’s not just the size on someone’s finger that you’re designing for it’s also the amount of control they have over that finger.

Provide alternate controls for touch gestures

Perhaps my biggest pet peeve among touch-based interactions is applications that rely solely on touch gestures for control. Take Apple Maps and Google Maps for example. It’s typical for me to act as a navigator for my wife, which means that the majority of the time I’m using these apps in a moving vehicle. For most people a pinch zoom gesture is quick and simple, but for me it’s almost impossible. At this point I have to use two hands to perform a pinch zoom and almost invariably I will include unwanted gestures in my attempt to perform one. This means that the simple task of moving around a map and zooming in and zooming out is incredibly difficult for me (if not impossible) in a moving car. Thankfully Google has an alternate input for zooming in and out. If I tap twice and hold the second tap I can swipe up or down to zoom in and out. Since this only requires one finger it’s much easier for me to achieve. Apple Maps has no alternative zoom function that I can find and has become largely useless to me. To illustrate this I recorded a video of me simply trying to zoom in and out in Apple Maps and another video of me zooming in and out as well as navigating on the map in Google Maps.

Notice how in Apple Maps the attempt at a pinch zoom gesture results in moving the map location and orientation rather than zooming. As this was done at my desk in my office imagine how much more difficult it would be for me in a moving car. In the Google Maps example you can see how much easier it is for me to move around and zoom using the alternate gesture. While I certainly appreciate Google Maps inclusion of a secondary method it is far from perfect. First, it’s non-intuitive, as I had to perform a Google search in order to discover it. Second, a far better solution would be to allow users an option in the settings that overlays zoom controls on the map. This would require no gestures and give people with motor control issues even more control over the map.

Touch gestures can be incredibly complex, some even requiring three fingers to complete. Don’t assume that your users will be able to perform even the simplest of gestures. By giving them intuitive access to alternate controls you will make your application more inclusive and easier to use for everyone.

Final thoughts

Designing for motor impairments requires as much consideration as other disabilities but doesn’t really have a single approach that guarantees accessibility. Rather you need to consider how your interactions might limit those with motor function disabilities and whether or not you can modify them to be more inclusive or provide alternate means of addressing them. Far from being a niche concern, visitors with some form of motor impairment likely make up a significant percentage of your users. I would encourage you to test your website or application with your less dominant hand. Is it still easy to use? If touch is involved try completing your interactions with a single finger other than your index finger. Can you still complete all the tasks? Designing with these restrictions in mind will create a more inclusive site and likely result in a better user experience for everyone.

Read more: