|

|

Bladder Calculi

- General considerations

- Relatively uncommon in United States

- Incidence has been decreasing due to better diet, control of infection

- Remain common in developing countries where it most often affects children

- Usually associated with urinary stasis

- But can form in normal individuals

- Recurrent bladder infections are associated with stone formation

- Renal calculi do not predispose to the presence of bladder calculi

- Most often affect males over 50 who have bladder outlet obstruction from an enlarged prostate

- Most common type of bladder stone in adults is uric acid stone

- In children, the most common type is composed of ammonium acid urate or calcium oxalate

- The chronic presence of bladder calculi has been associated with squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder

- Causes

- Bladder outlet obstruction is most common cause

- In females, causes may include cystocoele and bladder diverticula

- Urinary infections

- Neurogenic bladder

- Schistosomiasis

- Foreign bodies either left in place iatrogenically (Foley catheters) or placed there by patient

- Pathophysiology

- Most bladder stones form from a nidus inside the bladder, not in the kidney

- They may be single or multiple

- Most move freely in the bladder

- Clinical findings

- May be asymptomatic

- Pain, dysuria, frequency, hesitation, terminal gross hematuria

- Common symptom is sudden cessation of voiding accompanied by pain in the perineum

- Suprapubic fullness

- Imaging findings

- Calculi that form in a “hollow” viscus, such as bladder calculi, typically will have a laminated type of calcification

consisting of alternating layers of heavily calcified and matrix materials consisting of alternating layers of heavily calcified and matrix materials

- Initial imaging study of choice is a KUB (kidneys, ureters and bladder) radiograph using conventional radiography

- Uric acid and ammonium urate stones are non-opaque

- Jagged-edge calculi that resemble the game-piece in “Jacks” is called a “jackstone calculus”

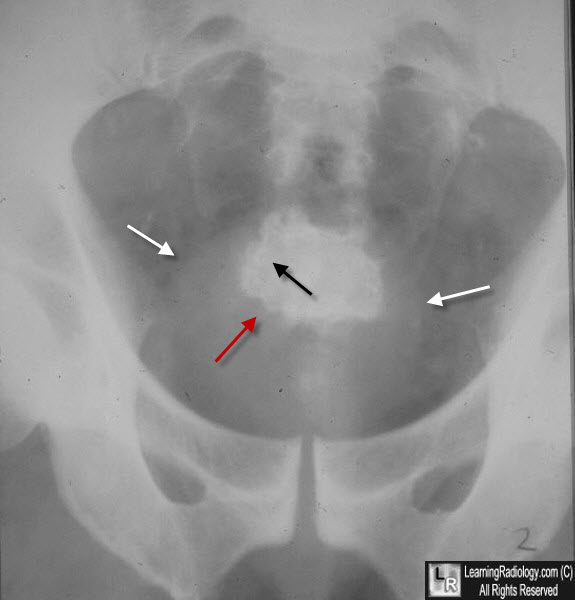

Jackstone Bladder Calculus. Close-up view of the pelvis shows a lamellated stone

(black arrow shows slightly denser layer of calcification) with multiple irregular margins (red arrow) within the confines of the soft tissue shadow of the urinary bladder (white arrows). The jagged edges are believed to form in a bladder that is trabeculated from chronic outlet obstruction, such as from benign prostatic hypertrophy (BPH).

- Unenhanced spiral CT scan is highly sensitive in diagnosing calculi along the urinary tract and has largely replace intravenous pyelography and cystography

- Cystoscopy is most common test used to confirm presence of bladder calculi

- Treatment

- Intervention may be indicated when there is acute urinary retention, gross hematuria or recurrent infections

- Most stones are removed via cystoscopy including the use of lithotripsy to fragment the stones

- Larger stones may require suprapubic surgery

Bladder Calculi. The image on the left is a conventional radiograph that shows several very large oval-shaped calcific densities in the region of the urinary bladder. The CT scan on the right, imaged for bone window, again demonstrates several large laminated calcifications in the bladder (white arrow).

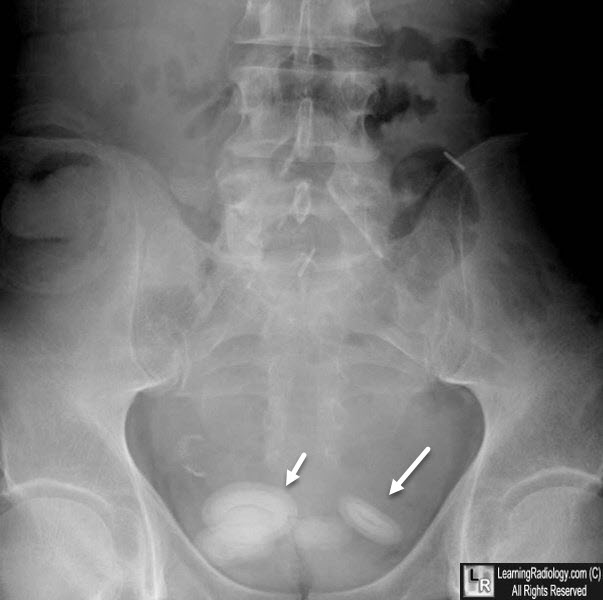

Bladder Calculi. White arrows point to multiple laminated calcifications

consistent with calculi in the region of the urinary bladder.

|

|

|

|

|