|

|

|||

Usha Rai, reports in 'Grassroots' magazine, on the Pani Panchayat experiment |

|||

|

Mahur village in Purandhar block of Pune district is like a green oasis in the parched, drought prone district of Maharashtra. Standing on a small hillock, for miles around green fields could be seen. At the base of the hillock is a minor irrigation tank into which the rainwater is harvested. This almost perennially full water body is the lifeline of Mahur village and its principle of equity in water distribution is its sustenance. In a country where rural people failing to get return from their agricultural lands are migrating to the big cities in search of jobs, in the 30 odd villages of Pune district where Vilasrao Salunkhe's pani panchayats are in operation, reverse migration has begun. Farmers who were getting barely 50 kg of bajra and jowar per acre and the annual income was Rs.2500 to Rs.4000 are now earning Rs.10000 to Rs.1 lakh from the same land. In addition to the traditional cereals, farmers in this area are growing wheat, onions, vegetables, a variety of flowers like marigolds, lilies etc., fruits and a cash crop that is not a water guzzler. The villagers practice organic farming. They have been able to provide employment to people from the adjoining villages and farmers who had gone to Pune and other cities for work are returning home. Engineer turned farmer The man who pioneered the radical technological and social innovations that repair and restore degraded water sheds and guarantee each family within the community an equal share of the water harvested, is an engineer with his own factory. It was in 1972, after the terrible drought that affected some 4-lakh people in Maharashtra that Mr.Salunkhe realised the need to intervene. There was just no water available for agriculture of any kind. Even drinking water was scarce and tankers would supply water for basic needs. Travelling extensively in the area, he found villagers breaking stones for road construction in a desperate bid to earn subsistence allowance from the government. The engineer in him realised that environmental regeneration and water shed development with the full participation of the community was the only solution. Rainfall in this region fluctuated between 250 mm and 500mm. He initially tried his ideas of water shed development on a 16-hectare plot of hillside in Naigaon village in Purandhar block. The land belonged to the temple trust but it was barren and uncultivable. He got the land from the trust on a 50-year lease and built a hut where he and his family lived and worked with the community. From 2 to 100 quintals. Conserving soil and harvesting water was given top priority. A series of contour bunds were raised to trap water and check soil erosion. At the base of the hill slope, a percolation tank that could hold upto a million cubic feet of water was constructed. A well was dug below it and water pumped from there up the hill slope for irrigating the fields. Trees were planted in the rocky areas; fruit trees grown in the more fertile areas and grass and shrubs regenerated on lands not being cultivated. Slowly production from the land increased. As against two to four bags of grain in an year, 100 quintals was harvested and enough employment was generated for the survival of five households and their cattle. Half an acre of irrigated land could provide a man's food needs for the whole year. The Naigaon experiment was ready for duplication in other parts of the state. Water had to be treated as common property resource with all villagers having equal rights and access to it. So five basic principles of the pani panchayat or Gram Gaurav Pratishtan were evolved . These are in operation to this day: These are in operation to this day: ~ Cropping is restricted to seasonal crops with low water requirement. Crops that require perennial irrigation and large amounts of water like sugarcane, bananas and turmeric cannot be cultivated in pani panchayat areas. The rules. ~ Water rights are not attached to land rights. If land is sold, the water rights revert back to the farmers' collective. ~ All members of community, including the landless have right to water. ~ The beneficiaries of the panchayat have to bear 20 percent of the cost of the scheme. They have to plan, administer and manage the scheme and distribute water in an equitable manner. With farmers paying 20 percent of the cost of lift irrigation, the government provided another 50 percent and the remaining 30 percent was provided by pani panchayat as interest free loan. The half a dozen landless people of Mahur who have joined the pani panchayat scheme have taken land on lease from landholders and put to good use their quota of water. They too have prospered and now some of them have bought land. Success spreads. In the early eighties when the cloth mill in which the villagers of Mahur were working closed down, they came together for their own water panchayat. Ten to 15 percent of the villagers who already had irrigated land have not joined the scheme. People living on the hilltop where the water could not be reached have also stayed away. As have carpenters and others doing different jobs. "Where the cost of development does not ensure returns, villagers have not joined in," says Lakhsman Khedar, who works closely with Salunkhe to ensure that the scheme stays on line. Though the region received close to 1100 mm of rain annually there was no storage facility, villagers recall. Today it is wonderful to see the prosperity of Ramchandra Sripathi Chavan, one of Mahur's early beneficiaries of the pani panchayat scheme. The old mud hut in which he lived till the eighties now serves as the godown for his crop of onions. A solid two-roomed cement house with galvanised iron sheets for roof is his new abode. A television set has been given pride of place. Of the four acres of land that he and his brothers own, two acres are now irrigated through lift irrigation. Earlier he was dependant on the rains and grew just bajra and jowar. He was able to harvest just 5 to 6 quintals in a year and earned just Rs.2500. Today he grows a mix of crops and his income has soared. Others from the village gathered to recount similar success stories. Niranjan Ganpat Rao Chavan and his brother have 12 acres of land. Now under the pani panchayat scheme 4.5 acres is irrigated. Earlier he grew groundnuts in the rainy season and bajra, jowar and rice and earned Rs.5000 to Rs.6000 in a year. Now he grows mogra, marigold and lilies in addition to wheat and vegetables and earns Rs.70,000 per acre of irrigated land. Niranjan, an MA, LLB had left his village in 1984 and was working in offices in Ratnagiri and Pune and sending home money. In 1987 he returned to Mahur to look after the irrigated lands. Like him Satyawan Gole has returned from Mumbai to work on his fields at home. Paying a donation, he has been able to send his son to an engineering college. Balasahib Chavan and his brothers own 11 acres of land of which three acres are under the pani panchayat scheme. Balasahib who studied till the 12th class is the village patkari, the man who operates the lift irrigation scheme, bills the villagers, collects payments and ensures that each member of the panchayat gets his due share of water. The pumps operate round the clock and Balasahib ensures that each acre gets water for three hours continuously. Though there is load shedding in the area, it is not as bad as it is in U.P., the villagers pointed out. Balasahib underwent special training on motor repair and electricity at Sashwath before taking charge in Mahur. He gets a salary of Rs.1500 as patkari. Every member of the panchayat contributes Rs.1000 a year towards maintenance. Balasahib who was earning Rs.9000 from his land now earns Rs.2 lakh a year. What is more, he has a special status in the village.

February,2001

|

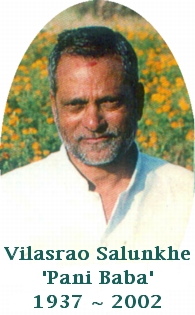

Reproduced by kind courtesy of Grassroots magazine. [Picture and obituary notes added in April,2002 soon after his death was announced.]

"Water has to be treated as common property resource with all villagers having equal rights and access to it"

Some little known facets of the man: he won the International Inventors Award, Sweden in the year 1985 for rural technology intitiatives. In 1986, he won the Jamnalal Bajaj Award for meritorious social service.

|

||