Condition of Mr. Segundo: Spending the days sighing.

Author: Richard Russo

Subjects Discussed: The origins of Bridge of Sighs‘s dual narrative, writing a long novel without an end in sight, Byron, characters who approach Lucy’s elbows, a protagonist’s blind spots, Marconi — the character and the telegraph, the American dream in post-World War II, hidden niches and the architecture of Thomaston, Gabriel Mock and his fence, the influence of Mark Twain, the chasm between the working class and the middle class, narrative dichotomies, the benefits of computers for ambitious novels, writing novels vs. screenplays, how Russo figured out corner market psychology, how operating schemes provide heft to narrative, Richard Ford’s realty knowledge, the origins of the “wrong end of the telescope” passage, teaching metaphors, dialogue and uptalking, John P. Marquand, a narrator setting down a story without awareness, the urge to tell a story, literary antecedents and unreliable narrators, writing in the dark, contending with massive topography and multiple characters, on being a natural propagator, the benefits of routine, violence and fights, Kitty Genovese, eccentric small-town teachers, Charles Baxter’s “Griffin,” howling, and using “gizzard” in dialogue.

EXCERPT FROM SHOW:

Correspondent: I’m curious as to where that moment, which seems to me your American Pastoral moment, came from exactly. How that came to be laid down.

Russo: You know, it’s funny. That particular metaphor of doors, of walking through doors closed behind you, and then having fewer doors to walk through and choose between, was the metaphor that I used to use when I was teaching to describe how plot worked.

Correspondent: Interesting.

Russo: When I was teaching my undergraduate and especially my graduate students. Plot is a very difficult — they say, how do you come up with a story? How do you know what happens first? What happens next? All of that. And I was trying to explain to them that the best stories, the best plots, are the ones that end up kind of paradoxically, you want to be surprised. But after the surprise, you want a sense of inevitability. Like that’s the only place the story could have gone. Those two things, that’s why a lot of books are disappointing. Because that’s a very hard effect to achieve. How can you surprise somebody even as, after they register the surprise, they say, “Oh, of course. This is the only way it can go. This is the only way it could have gone.” Those two things are antithetical. And yet the best books always have that. That coming together. So I was always looking for a metaphor to explain that to people. To my students. And I’d say, all right. Think of it this way. You’ve got a thousand doors. You choose one. You walk through it. Now you’ve got five hundred doors. You walk through that. You’ve got two hundred and fifty doors. Every time I started explaining that to students, that there were fewer and fewer doors, that was going to provide the inevitability. But there was still the surprise. You didn’t know. Every time a character makes a decision, it seems that there are so many other possibilities. So it’s a series of surprises that ends up with a sense of inevitability. But as I explained that to my students, and as I was writing this book, it occurred to me that’s also a description of life and destiny.

It is important that I respond to recent provocative claims made

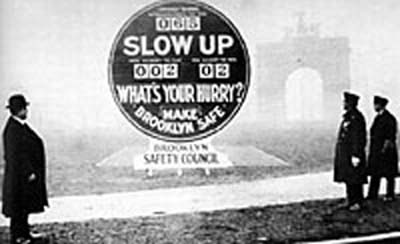

It is important that I respond to recent provocative claims made  After breakfast, I found myself offering an impromptu historical tour of Brooklyn, learning in media res that Grand Army Plaza at one point had a

After breakfast, I found myself offering an impromptu historical tour of Brooklyn, learning in media res that Grand Army Plaza at one point had a

Starting with the obnoxious essay, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?,” Wilson declares, “I got bored with the Thinking Machine and dropped him.” He dismisses two Nero Wolfe books “sketchy and skimpy” and writes of The League of Frightened Men “the solution of the mystery was not usually either fanciful of unexpected,” failing to consider the idea that a good mystery may not be about the destination, but the journey. He declares Agatha Christie’s writing “of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read,” but fails to cite several specific examples, before concluding:

Starting with the obnoxious essay, “Why Do People Read Detective Stories?,” Wilson declares, “I got bored with the Thinking Machine and dropped him.” He dismisses two Nero Wolfe books “sketchy and skimpy” and writes of The League of Frightened Men “the solution of the mystery was not usually either fanciful of unexpected,” failing to consider the idea that a good mystery may not be about the destination, but the journey. He declares Agatha Christie’s writing “of a mawkishness and banality which seem to me literally impossible to read,” but fails to cite several specific examples, before concluding: