Grant B. asked me to post the derivation for the right and left Kan extension formula used in previous Kan Extension posts (1,2). For that we can turn to the definition of Kan extensions in terms of ends, but first we need to take a couple of steps back to find a way to represent (co)ends in Haskell.

May 2008

Mon 26 May 2008

Kan Extensions III: As Ends and Coends

Posted by Edward Kmett under Category Theory , Haskell , Kan Extensions , Mathematics[58] Comments

Thu 22 May 2008

Kan Extensions II: Adjunctions, Composition, Lifting

Posted by Edward Kmett under Category Theory , Comonads , Haskell , Kan Extensions , Monads[48] Comments

I want to spend some more time talking about Kan extensions, composition of Kan extensions, and the relationship between a monad and the monad generated by a monad.

But first, I want to take a moment to recall adjunctions and show how they relate to some standard (co)monads, before tying them back to Kan extensions.

Adjunctions 101

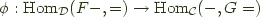

An adjunction between categories  and

and  consists of a pair of functors

consists of a pair of functors  , and

, and  and a natural isomorphism:

and a natural isomorphism:

We call  the left adjoint functor, and

the left adjoint functor, and  the right adjoint functor and

the right adjoint functor and  an adjoint pair, and write this relationship as

an adjoint pair, and write this relationship as

Tue 20 May 2008

Kan Extensions

Posted by Edward Kmett under Category Theory , Comonads , Haskell , Kan Extensions , Mathematics , Monads[55] Comments

I think I may spend a post or two talking about Kan extensions.

They appear to be black magic to Haskell programmers, but as Saunders Mac Lane said in Categories for the Working Mathematician:

All concepts are Kan extensions.

So what is a Kan extension? They come in two forms: right- and left- Kan extensions.

First I'll talk about right Kan extensions, since Haskell programmers have a better intuition for them.

Mon 19 May 2008

Elgot (Co)Algebras

Posted by Edward Kmett under Category Theory , Comonads , Haskell , Mathematics , Monads , Squiggol[459] Comments

> import Control.Arrow ((|||),(&&&),left) > newtype Mu f = InF { outF :: f (Mu f) }

I want to talk about a novel recursion scheme that hasn't received a lot of attention from the Haskell community and its even more obscure dual -- which is necessarily more obscure because I believe this is the first time anyone has talked about it.

Jiri Adámek, Stefan Milius and Jiri Velebil have done a lot of work on Elgot algebras. Here I'd like to translate them into Haskell, dualize them, observe that the dual can encode primitive recursion, and provide some observations.

You can kind of think an Elgot algebra as a hylomorphism that cheats.

> elgot :: Functor f => (f b -> b) -> (a -> Either b (f a)) -> a -> b > elgot phi psi = h where h = (id ||| phi . fmap h) . psi

Fri 16 May 2008

Wed 14 May 2008

Generatingfunctorology

Posted by Edward Kmett under Haskell , Mathematics , Type Theory[59] Comments

Ok, I decided to take a step back from my flawed approach in the last post and play with the idea of power series of functors from a different perspective.

I dusted off my copy of Herbert Wilf's generatingfunctionology and switched goals to try to see some well known recursive functors or species as formal power series. It appears that we can pick a few things out about the generating functions of polynomial functors.

As an example:

Maybe x = 1 + x

Ok. We're done. Thank you very much. I'll be here all week. Try the veal...

For a more serious example, the formal power series for the list [x] is just a geometric series:

Tue 13 May 2008

Towards Formal Power Series for Functors

Posted by Edward Kmett under Category Theory , Haskell , Mathematics , Type Theory[458] Comments

Wed 7 May 2008

I did some digging and found the universal operations mentioned in the last couple of posts: unzip, unbizip and counzip were referenced as abide , abide

, abide and coabide

and coabide -- actually, I was looking for something else, and this fell into my lap.

-- actually, I was looking for something else, and this fell into my lap.

They were apparently named for a notion defined by Richard Bird back in:

R.S. Bird. Lecture notes on constructive functional programming. In M. Broy, editor, Constructive Methods in Computing Science. International Summer School directed by F.L. Bauer [et al.], Springer Verlag, 1989. NATO Advanced Science Institute Series (Series F: Computer and System Sciences Vol. 55).

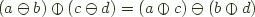

The notion can be summed up by defining that two binary operations  and

and  abide if for all a, b, c, d:

abide if for all a, b, c, d:

.

.

There is a cute pictorial explanation of this idea in Maarten Fokkinga's remarkably readable Ph.D dissertation on p. 20.

The idea appears again on p.88 as part of the famous 'banana split' theorem, and then later on p90 the above names above are given along with the laws:

fmap f &&& fmap g = unfzip . fmap (f &&& g) bimap f g &&& bimap h j = unbizip . bimap (f &&& h) (g &&& j) fmap f ||| fmap g = fmap (f ||| g) . counfzip

That said the cases when the inverse operations exist do not appear to be mentioned in these sources.

Mon 5 May 2008

Twan van Laarhoven pointed out that fzip from the other day is a close cousin of applicative chosen to be an inverse of the universal construction 'unfzip'.

During that post I also put off talking about the dual of zipping, so I figured I'd bring up the notion of choosing a notion of 'cozipping' by defining it as an inverse to a universally definable notion of 'counzipping'.

Sun 4 May 2008

Kefer asked a question in the comments of my post about (co)monadic (co)strength about Uustalu and Vene's ComonadZip class from p157 of The Essence of Dataflow Programming. The class in question is:

class Comonad w => ComonadZip w where czip :: f a -> f b -> f (a, b)

In response I added Control.Functor.Zip [Source] to my nascent rebundled version of category-extras, which was posted up to hackage earlier today.