Tuesday, July 15, 2008

Going Off

So, in honor of that last bit, I'm going to rep0st something I put up on my Newsgroup a couple of years ago, following the 2006 World Science Fiction Convention:

[originally posted Sept. 5, 2006]

I was watching the News Hour on PBS last Friday, the Shields and Brooks segment, and Jim Lehrer asked a question about Bush’s latest PR offensive, equating the War on Terror and War in Iraq (two phrases Bush always uses interchangeably) to the Cold War and WWII. And Mark Shields. Just. Went. Off. He was nearly ranting, forcefully demanding to know why, if it was all so important, why the country hadn’t been put on a war footing, why there weren’t enough troops in Iraq, why taxes hadn’t been raised, etc. etc. etc.

Brooks was obviously taken aback, and tried his best to shift the argument, talk about how the country would never stand for such measures, and so forth. But mostly he looked nervous and, well, dare I say it, wimpy, irresolute, even lost. After all, Shields is the liberal; he’s not supposed to be the one spitting fire.

The World Science Fiction Convention isn’t anywhere close to the political mainstream, actually. Most convention going fans are college-educated, intellectual-leaning, and more respectful of science rather than, say, religion. Certainly there are plenty of right-leaning fans, but they tend toward the libertarian or Social Darwinian right, rather than the religious right that forms the core of the current Movement Conservatism.

Still, I’ve heard plenty of support in the past from various SF types for various portions of the Conservative Movement agenda, especially the anti-tax, liberal bashing part of it.

Not this last convention, however. In fact, several times, some from panelists, but just as often from ordinary convention goers, the subject would flash over to current politics and the Bush Administration and someone would. Just. Go. Off. On a tirade, a screed, a rant, a whatever-you-want-to-call-it.

And there would be no response. Not even afterwards, in the men’s room, where all the important political thoughts are voiced. No one is willing to say in public, or even semi-private, that they support the Bush Administration.

The secret ballot covers a lot. It especially covers a lot of bigotry. David Duke the white supremacist always polled about 10% higher in the actual race than he did in preliminary opinion polls. So it’s always hard to predict elections beforehand, especially when fevers run high on issues like immigration, where race matters even more than it does otherwise.

But authoritarians are bullies, and the truism is true: bullies are cowards. At a certain point, pulling in your horns becomes reflexive, especially when you’re not sure what you’re voting for in the first place. Moreover, bullies really, really, hate to lose. Better to not fight, then tell yourself that you’re the victim here.

So while I’m not exactly predicting a surprising shift in voter turnout this fall, with the authoritarian right sitting on their hands, it wouldn’t surprise me one bit.

Monday, July 7, 2008

Does Science Fiction (Still) Matter?

But in "Why Science Fiction Matters," I argued that science fiction is (or was) more than an escapist literature of popular culture, that it fulfilled a central role in the lives of at least one major segment of the post-war generation, the upwardly mobile children of working class (or agrarian) parents. For the tech oriented Baby Boom generation, plus a segment of a couple of generations before and after, SF provided a world view, including a program for the future, access to a social network, and a window into transcendence of the sort that usually falls to religion and philosophy.

The period of SF ascendance can be demarcated by the two major science fictional events of the 20th Century, the advent of nuclear weapons and the Apollo Space Man-in-Space Program. In truth, I would tend to move the starting point a little earlier, to the beginning of World War II, because that war was, in many ways, a science fictional war. New weaponry, especially radar, but also missiles, submarine technology, and so forth, played a major role in the fighting and winning of the war. Moreover, commentaries prior to the war speculated on whether or not the next war would be the end of civilization. And the savagery loosed during that war met or exceeded the most nightmarish visions of pulp literature.

At the other end, the lunar landings and the space program generally seemed to validate everything that had ever been written about space exploration, and an entire generation was sure that colonies on the Moon and Mars were just around the corner. That they were disappointed in this contributed to the anti-government backlash that occurred thereafter. To this day, there are SF fans who are sure that it was only the incompetence of U.S. bureaucrats that stood in the way of their dreams of interstellar civilization.

In fact, it was reality that nixed the deal. Space if far bigger and more hostile (and less economically valuable) than most people imagined.

That's the problem with reality. It keeps intruding and messing up our dreams. There was a time when it seemed like science and scientific authority would loom large on the political landscape. But science kept delivering bad news, like warning about environmental degradation, limitations on energy use, changes in the global atmosphere and the implications thereof.

And, in truth, SF had always been a bit anti-establishment when it came to science. Astounding, under Campbell, spent over a decade pushing ESP/PSI, to no good effect. Then there was the entirely embarrassing Dianetics episode. Toward the end, a good many SF types jumped on the SDI bandwagon, as yet another excuse for space research, just as solar power satellites (a truly silly idea), had gripped imaginations earlier, and still do, to this day.

But subsequent generations took a look at all this and saw what was basically an escapist literature that had been co-opted into a number of big budget motion pictures. Fun, but nothing to wrap your life around. Now, things like World of Warcraft take more of the escapist freight than does reading SF. For religious transcendence, people are showing a disturbing tendency to turn to—religion. And, as I say, the Authority of Science has a lot of people claiming to speak for it, or attacking it outright.

So where does that leave science fiction? The aging of the SF fan community has been much remarked upon, and it's a fact of life. To my eye, it doesn't really look like SF is currently the place where someone with something to say goes to say it (I suspect that blogging now occupies that ground), nor is it the place where people go to read what such people have to say. SF has spawned several sub-genres, like military SF, alternate history, paranormal romance, and the like, so maybe that is where the energy has gone, into smaller and smaller niches.

The center no longer holds, or at least it no longer holds that much attraction. But maybe that's just me being an old fart.

Tuesday, July 1, 2008

Oracles

The two protagonists are a galactic exploration team, and they have discovered that the galaxy is awash with Homo Sapiens, practically one inhabited world in every viable solar system, and all of them primitives who greet space explorers with either worship or homicidal intent. It's a puzzlement.

Then they come across a civilized world, but one that is oddly decadent. They have such technology as automatic translation machines, but have no idea how they work. When asked, the inhabitants reply, "We asked the Oracle how to make one and it told us."

So, first error in presentation. You don't build things by just being told how to make them. To build a translator (or automobile, or even a stone house) you need pre-existing infrastructure like semiconductor fabs, or foundries, or stone quarries. Knowledge alone isn't enough.

Next, one source of answers simply would not work for an entire world. This is the alien-planet-as-desert-island analogy that I once railed against when critiquing Clarke's Law. A civilized world has billions of people on it, far too many to crowd into a room.

But the Oracle does indeed reside in a room, and our explorers are given an audience. It reveals that it was created by an extra-galactic race (from the Magellenic Cloud) as a weapon that worked by answering all questions truthfully. This destroys the institution of science in those who possess it (no need to pursue answers when they are handed to you an a plate), and when taken to a empire's home world, wrecks said empire.

One of the two explorers wants to steal the Oracle and take it back to Earth, rigging it to answer only his questions. The other wants to head back empty handed and warn Earth. They fight. The first guy dies. The second realizes that he is now stranded, since their ship required two men to operate. But the Oracle could tell him how to save his own life, so….

In one of the Foundation stories, Asimov makes a swipe at what happens when you trade science for scholarship, i.e. when you stop experimenting and just look up the answers. I never bought that argument. Nobody verifies everything that they are told under the authority of science, to attempt to do so would result in another end state—where science keeps reinventing the wheel, over and over again.

However, "Perfect Answer" gets the reaction of the two explorers correctly, or, more specifically, the one that wants to monopolize the gizmo. That is how it would actually work, so our travelers should not have found a happy-go-lucky decadent society, they should have found an authoritarian state in the grip of those controlling access to the answers from the Oracle.

Now you can replace Oracle with "simulation model." But you still need that infrastructure that I spoke of earlier. In science, the infrastructure consists of scientists and the community of science. The community of science is not command-and-control oriented, as many have discovered, to their discomfort.

There is a difference between authoritative and authoritarian, which some people get and some people do not. Authoritarians don't get it. They never do.

Wednesday, June 11, 2008

Probably Not

The first science fiction and fantasy convention I ever went to was something called CreationCon. There is now a regular comic convention by that name, but the CreationCon I went to with Ben, Johnny, and the Albany gang had nothing to do with comics. God knows, it had everything else in it though.

Someone had the idea that there was a crying need for a convention bringing together science fiction, fantasy, new age ideas, and the occult. I mean, it sounds like it might work; it just turned out that fantasy writers like L. Sprague deCamp and Lin Carter considered “the occult” to be pseudo-scientific rubbish.

But it was fun. I met David Gerrold for the first time, just after When Harlie Was One came out, and a small group of us had lunch with him. I’ve met David maybe five or six times now, and every time it’s as if we’ve never met before, which is kinda cool, actually.

I also started my Freak File at that convention. That’s my collection of fringe material. Years later, Larry Jannifer and I spent an evening comparing notes on the subject. He called his the “Nut Shelf” so you can see where this is going. I also once loaned my collection to Jim Turner of Ducks Breath Mystery Theater, after seeing his one man show “The Brain that Wouldn’t Go Away.”

I think my real prize from CreationCon was Norman Bloom. Bloom was handing out copies of his self-published ‘zines, really well produced things, photo-offset on news stock, with sturdy staples, the works. Bloom thought he was Jesus, or, more accurately “The Second Coming of Christ.” As nearly as I could tell, he was serious, and harmless. His booklets were filled with proofs of the existence of God, all of which boiled down to the proof of improbability. You see this a lot in Creationist circles, “The odds of life forming are similar to having a 747 appear after a tornado in a junkyard.” Bloom, god bless him, stripped the whole thing down to basic fundamentals. He’d open up the phone book, look at a phone number, and calculate the odds of that particular number appearing. For a seven digit number, assuming all the numbers are random (which they aren’t of course, but I’m not going to stop a crazy man on a roll), you’re talking 100 million to 1. And there are hundreds of thousands of numbers! Good lord, the improbability of it!

If you didn’t like that one, the one about how unlikely it is to have the Moon be just the right size and distance to just barely, yet completely, eclipse the Sun, well, tornado in a junk yard, here we are.

Bloom was, I believe, an engineer, so he had just enough statistical knowledge to get him into trouble. Nevertheless, the problem that he fastened onto is a real problem. It’s known in philosophy as the Plenitude Principle, the notion that if the universe if big enough (infinite sounds about right), then everything that is possible must occur. Or alternately, why do some things happen when other, seemingly just as likely, things don’t?

Regular probability theory finesses the problem nicely: the probability of any event that has happened is 1. Baysean statistics allow a bit of a scew from that: you can’t always be sure that something has happened, so the probabilities then become a measure of your own ignorance.

The Wikipedia article on the Plenitude Principle goes all the way back to Aristotle, though it misses Nietzsche’s take on it: eternal recurrence. Old Friedrich decided that if everything happened once, it would happen over and over again; infinity is big enough, after all. Hard to argue with that, though it’s pretty easy to ignore or dismiss.

A lot of people have taken the entire “many worlds” idea a step beyond, to the notion that everything that you can imagine happening happens somewhere. The real problem with that line of thinking is that it’s possible to imagine things that can’t actually happen, like flying horses and FTL spaceships. Then there is the extended problem of people who think that they are imagining something when what they are really doing is imagining that they are imagining something. That, it turns out, is pretty easy. Just ask Norman Bloom.

Monday, June 9, 2008

On Lying

I remember a documentary on I. F. Stone, in which he disclosed that the real secret of his journalism was in listening to the exact words of politicians and government officials in order to spot the slight verbal tics that indicated the legalistic lie, the carefully worded truth meant to convey the wrong impression. I have a friend who was positively incensed when he learned of Clinton’s mislead, saying “I did not have an 8 year long affair with Jennifer Flowers,” when actually it was a 12 year affair. I’ve lost touch with my friend, so I don’t know how he felt about Cheney/Tennet’s description of the link between Saddam and bin Laden: “We have solid reporting of senior level contacts between Iraq and al Qaeda going back a decade” which translated to “there have been no real contacts for the past 10 years.”

But I am reminded of a quote I recall from a high official in the last days of Polish communism, “The purpose of propaganda is not to get people to believe lies. The purpose of propaganda is to kill the idea of truth.” Twisting truth is more dangerous than merely telling lies; when the truth twists, the very ground beneath your feet becomes treacherous.

I happen to be a close to incompetent liar. I’m just not very good at it. So the Heinlein prescription held some attraction when I was younger and more naïve. But twisted truth still has threads of truth in it, and is easier to pull apart than a well-constructed fabrication. So let me start with the advice, if you’re going to lie, then tell a lie. Be a mensch. At least admit to yourself that you’re making it up. That, at least, saves you from the conceit that you’re better than those you’re lying to. The lie-by-telling-the-truth game lets you tell yourself that it’s your audience that’s too dim-witted to figure out what you’re really saying.

The next important point is that narrative is important. The best lies tell a good story, one with all the proper narrative tricks, like foreshadowing and thematic resonance. All well and good.

But the most important thing about a good lie is to tell your audience what they want to hear. And what they most want to hear is that they are important, they are worthwhile, and they are better than someone else.

That's also my advice on how to write popular fiction, too. And I have trouble with the "popular" part, another indication as to just how poor a liar I am.

Wednesday, May 28, 2008

The Vocoder

The vocoder was a real device and a pretty cool gizmo. It took a sound sample and fed it through a series of notch filters, very narrow bandwidth filters, and measured the amplitude of each narrow frequency, making it essentially a device for producing a power spectrum. That’s the encoding part. The decoder essentially reversed the process. If you put enough bands into it, you can get more-or-less recognizable speech out of the decoder, at a small fraction of the bandwidth of full speech.

The trick is that you are tossing out phase information, the connection between each sound frequency, so you never get the sound of real speech out of a vocoder, no matter how many frequencies you segment the sound into. What you get is one of those “robot voices” that you’ve heard in movies and TV since the 50s. You can also twiddle with the playback by changing the nature of the original frequency set, or even imposing a voice envelope onto other sounds. That’s how Disney and Bell Labs TV specials got all those “talking instruments” ‘way back when. I’m not sure about Gerald McBoing-Boing

The unnaturalness of the vocoder output sent sound researchers back to an older vision: vocal tract modeling. I’m told that before the phonograph, there was a lot of interest in “talking machines,” literally, machines that talked like people do, by expelling air through a vocal tract. Vocal tract modeling attempted to do the same thing, only digitally, and it met with about the same success: not much. It sounded okay if restricted to some very amenable phrases (“We were away a year ago”), but more frequently, it was just unintelligible.

Eventually, cheaper hardware, especially memory, came to the rescue. Current speech generators simply look up words in a dictionary, and spit out the correct phonemes, linked together with some special rules. They can sound fairly realistic, provided your idea of realistic speaks with a Swedish accent. Stephen Hawking uses one of these types of speech synthesizers, by the sounds of it, but he has it set to sound more like the old vocoder style of robotic intonation, perhaps to emphasize that it is a robotic voice he’s using, or maybe because Hawking is a bit of a card.

Tuesday, May 20, 2008

Maybe It's That Simple

Also, in the first part of his essay, he's dealing with some of the issues that are often trotted out when people discuss science fiction, and, more specifically, why some people don't like science fiction, and perhaps why some people have trouble reading science fiction. This is often summed up in the phrase, "The door dilated," which is supposed to signal the savvy SF reader that we're not in Kansas anymore, but which troubles the regular reader, because, perhaps, we're not in Kansas anymore.

I'm actually giving away a bit of my own argument here with that last sentence, because the sort of literary analysis that Barnes is critiquing calls these things "reading protocols," and suggests that non-sf readers either do not possess the protocols that make sf readable, or they do not enjoy using those protocols.

My own suggestion, which Barnes does not really mention (though I'm sure he's considered it), is that some people just don't like science fiction. It's not as if this is a feature of the landscape that is confined to literature; there are plenty of sf movies, tv shows, comics, etc., and there are many, many people who simply don't care for them. The same is true of various sorts of fantasy. A friend of mine had a long-running (and joking) argument with his wife and daughter about Buffy, the Vampire Slayer. They loved it; he refused to even watch it. He preferred The Sopranos, which is a different kind of wish fulfillment fantasy, but a fantasy nonetheless. He even agreed with this when I pointed it out. However, he still preferred The Sopranos.

Similarly, there are currently entire genres that are, by classical standards, science fiction, but which regular science fiction readers disdain because they don't speak to whatever said sf readers really want. I'm thinking here of the cross-genre romances, the paranormal romances, the time-travel romances, and so forth, which spoil all the good sf action with that "chick lit" stuff.

In any case, I'm pretty sure that Barnes skips over this part of the argument because he wants to get on about reading protocols generally, and what he calls "dip and flip," as a result of a series of observations he's made of people reading in public places:

One thing stood out vividly: about half the observed readers who appeared to be under 35 began each new page by looking at the center, scanning outward from there in a sort of loose clockwise spiral, and then beginning to read left-right-diagonal-down once they had found something of interest. From eavesdropping I could tell they were looking for a word or phrase to catch their attention, checking back to contextualize it, and then reading only as long as the text was still about that word or phrase (or until another word or phrase took over as focus of interest). And like many of the ad-readers and sentence-excerpters, their conversation indicated that for them, that word or phrase was what the article was "about."

(I put "about" in quotation marks because in different reading protocols "about" seems to mean something different to some readers than it does to others.)

Barnes correctly notes that the "dip and flip" protocol screws up any attempt to convey ordered information, so it is particularly vexing to technical writers and the writers of clean, linear fiction. Indeed, as a card carrying member of both groups, let me suggest that Barnes is being very kind by not suggesting the traditional label for such reading protocols: functional illiteracy.

Of course this is an argument that goes back forever, and includes the Evelyn Woods "Speed Reading" controversy of decades ago.

"What is astonishing is that they think that 80% comprehension is enough. Kennedy was a speed reader. 'Bay of Pigs?' That must have been in that other 20%." –The Firesign Theater.

Barnes spends the rest of the article on providing some tips for how stodgy old linear writers can tap into the "dip and flip" market, primarily by telling their stories in small, bite sized chunks, each of which must have a sugar glaze and a crunchy center. And, truly, I'm pretty much fine with that as far as it goes. Make the scenes shorter, put in some self-contained vignettes, make both geography and point-of-view less static, and more energetic, sure. I'd have done even more of that in SunSmoke, if I'd thought I could get away with it.

But, ultimately, I don't think that there is as much gold in them thar hills as we'd like to think. It's true that the number of casual readers dwarfs the number of dedicated ones, but it's not obvious that one can make all that much of a cake from crumbs. And if I want to really connect with a readership, I think I'll go after readers who want to connect back.

Sunday, May 11, 2008

Versions of Immortality

At least that is my interpretation of such oddities as the “weight of the soul” idea (21 grams?), which lots of people seem to buy, even those who profess to believe in the “immaterial soul.” Still, maybe people who believe that something immaterial nonetheless has weight are merely ignorant of what “immaterial” means.

In any case, you don’t have to be a science fiction fan to hope for “scientific immortality” though I suspect it helps.

One of the current magic wands, The Singularity, is substantially science fiction-y. As nearly as I can tell, this is the idea that we’ll soon have artificial intelligence and that said intelligence will be able to evolve exponentially to higher and higher intelligences, and at some point said AIs will become indistinguishable from God, even down to the part about loving each and every one of us so much that He, She, or It will grant us physical immortality. Or maybe we get mental immortality, by uploading each of our minds/souls into the Great AI, to dwell in the presence of the Lord forever, amen.

Apparently I’m not much of a fan of The Singularity.

Of course, the upload/download thing has been around for quite a while (Tron, anyone?). It’s an extension of an older idea, that Everything Is Information. I once had an immortalist on the Compuserve Science Forum try to convince me that the information contained in my brain is important (which I certainly believe), so important that it constitutes my essence (which I don’t buy for a minute). Yes, without my memories I’m not me anymore, but putting my memories into some other brain doesn’t make him me, not even if it’s my genetically identical clone. It just means there’s two guys walking around thinking they are me, which I don’t believe is the same thing, and neither would they, I’ll bet.

The Pop Culture version of immortality is that our souls are made of some sort of Special Matter. We know that it’s matter because it has weight (see above), is immortal (which, in actuality, matter more-or-less is and spirits aren’t, nearly as I can tell), and can give you a body image even without a body wrapped around it. In other words, a ghost made out of ectoplasm, an astral projection, a hoodoo of some sort. When physicists go off into these nether realms, they start talking about the “physical basis of consciousness” and try to conjure up special particles, special physics, or paraphysics. Going back a ways, you get physicists who are interested in parapsychology.

J. B. Rhine, who kicked off the whole parapsychology movement, was pretty specific about his aims. He believed that it should be possible to directly perceive God. Of course, if there were some aspect of the mind that was not part of physiology and beyond conventional physics, then all the wonders of the immortal soul would be real, even if not necessarily concrete.

John W. Campbell bought it hook, line, and plot device, so we had a couple of decades worth of psi stories, whose tropes are part and parcel of science fiction, so well established that you really don’t even need to explain them any more. Though they are déclassé in the “cutting edge” part of SF, they are well represented in mass media SF, and will no doubt outlive us all.

Later we had cryonics, the Disney version of the Egyptian afterlife, as it were. That Uncle Walt is in cryonic suspension is an urban legend engendered by the coincidence that there was publicity for cryonics on the same day Disney died, and some reporters covered both stories, with speculative results. After people began to realize just how much damage a frozen corpse had sustained, nanomachines came to the rescue, at least fictionally. For all I know there’s a nanotechnology story that has someone resurrecting Egyptian mummies. Or maybe there will be soon. My favorite nanotech story was the one where Gregor Samsa wakes up one day to discover himself transformed into a giant jelly donut.

I remember a story, by del Rey I think, that begins with the observation that every ghost story, even a horror story, is a bit hopeful, since if the ghost survives after death, then that is evidence that death isn’t the end. As I recall, the story then specifically torpedoes that hopefulness, but most ghost stories do indeed fulfill that purpose, to provide just a little more confirmation that death might not be the end to your own personal viewpoint.

Science, of course, has powerful mojo, and people generally would like to appropriate that mojo for their own ends, including the “be not afraid” part of religion. The crassest kind of comfort is the kind that says that what you’re afraid of doesn’t exist, in this case that death is somehow contingent, that there are loopholes (just like for taxes!), and all will be taken care of because someone who is all powerful is watching out for you.

For my own part, I remember being struck by a line in an F&SF story many years ago. One character asks another (who, if memory serves was the Devil), what would happen to his soul when he died. The Devil answered, “What happens to the information in a book when you burn the book?”

Years later, at the memorial service for my first sensei, someone remarked, “In some of the Zen traditions, the soul is a candle flame; it doesn’t go anywhere when it goes out. But one flame can light many others while it lives.”

If you spend all your efforts in trying to keep the one candle lit, you might not be lighting the other candles. That, ultimately, is the danger of promises of immortality, that you spend so much of your life trying to compensate for your own fear of death that you fail to expend effort on living your own life, whatever that may mean to you.

Friday, April 18, 2008

See How It All Fits Together

In a more recent essay, "PAN", I noted that there were some features of the chemistry of that compound that I'd gotten right because of a detailed analysis, a I-knew-what-I-was-doing sort of thing, which is more bragging, of course, but I noted that, science being what it is, I was only a little bit ahead of the curve. The rate constants that I'd had to adjust to make my simulations work were routinely measured as being what I'd needed only a little while after I did my work, and the ordinary workings of science would have produced models that did the right thing, even if no one was paying attention.

In "The Linear Hypothesis," I remarked that sometimes (in fact, pretty often) scientific models are used for purposes of policy and decision making, and a model is often chosen to make that task easier, because, well, that's the purpose at hand. Sometimes this is done for good reasons, like selecting a conservative model in order to observe "The Precautionary Principle," where we are dealing with asymmetric error; if an error in one direction is vastly more costly than an error in the other direction, then simple caution suggests using the more conservative model, even if there is some weight of evidence on the other side.

Anyway, I've just been talking to an old colleague, who tells me that one major smog kinetics model has been "fixed" so that it no longer shows that weird toluene behavior that we actually proved to exist. The experiment that proves it is now considered "old" (as if chemistry somehow goes bad with age), or "sloppy," or the result of experimental error. Not that anyone is bothering to replicate it, you understand.

I expect that it has to do with it just being too confusing to have models tell you that sometimes adding one pollutant can produce less of another pollutant. Or something like that. The rationalizations sound pretty sad, however.

We've been hearing a lot lately about the ways and methods that various players in the Bush Administration have been tampering with scientific reports, muzzling scientists, and twisting the system to their own ends. This is, of course, despicable. What I am saying here is that I've seen a lot of this sort of thing throughout my entire scientific career, coming from every policy quarter. Yes, the Bush Adminstration does it, and has been totally shameless about it. But they had plenty of precedent from the Tobacco Industry, the Oil Industry, the Pharmaceutical Industry, and, I will add, Environmental organizations and regulators. When people have an ax to grind, they will first grind it on the facts of the matter, or at least the theories and models that are used to codify the facts.

The "Probability Engine" that the time meddlers found in Destiny Times Three by Fritz Leiber was originally a simulation engine, developed by advanced beings to calculate the probable results of various actions, and to avoid the worst actions and their consequences. The horror of the story is that the device came into the possession of humans, who, with the best intentions (but insufferable arrogance) used it to create those dystopian worlds, rather than simply model them.

I do so hope that this is not, ultimately, a metaphor for science in the hands of human beings.

Tuesday, April 8, 2008

Destiny Time Three

I recently reread Destiny Times Three, by Fritz Leiber. Given that Leiber is my favorite science fiction and fantasy writer, and DT3 is possibly my favorite of all his longer works, it may not require explanation as to my purpose in the endeavor. However, given that I don't even mention DT3 in my long essay on Leiber, "Sleeping in Fritz Leiber's Bed," I may have some 'splaining to do. Moreover, there was at least one ancillary purpose that bears exploring.

In his autobiographical writings, Lieber says that his original conception of Destiny Times Three was grandiose. He intended a work of around 100,000 words at a time when "complete novel in this issue" meant a novella of maybe 30-40,000 words, and 60,000 words was the standard length for a book.

But DT3 was a victim of the WWII paper shortages, and, by editorial demand, Leiber cut it down to the more standard "short novel" length, so that it could fit into two consecutive issues of Astounding, losing, by his own account, all of the female characters and a great deal of the richness of the worlds he'd created. I had something similar happen to me with the magazine version of "SunSmoke," but I got to make up for it somewhat when I expanded it to book length. Leiber's full version of Destiny Times Three is lost forever.

Dammit.

The general story of DT3 is that there are parallel worlds, but not due to the natural workings of physics, etc. Instead, sometime in the late 19th Century, an alien device was found by a fellow who fancied himself a scientist. He enlisted the assistance of seven other individuals, because it took eight minds to operate the thing, and they used it to slowly create a "utopia," by splitting the world at crucial decision points, observing which world was most to their liking, then "destroying" the "experimental control" worlds. Very scientific.

In fact, they had not destroyed each of these worlds, but merely placed them beyond their own ability to access them, "swept them under the rug" as it were.

The protagonists on Earth 1, the utopian world, are Thorn and Clawly, who rather closely resemble Fahfred and Gray Mouser, or, more accurately, Lieber and his friend Harry Fischer, at least in their imagined incarnations. It's also not a great leap to consider the duo as Thor and Loki (or Loke, as Leiber spells it), given the former's name and the latter's specific comparison to Loke as the tale unfolds. Also, Norse imagery is an ongoing motif throughout the story.

On Earth 1, the power of "subtronics" has been harnessed, subtronics being a Campbellian trope for a sort of "unified field theory" that can also be found in Heinlein's Sixth Column/The Day After Tomorrow, itself a reworking of material supplied by John W. Campbell. All have access to its power, and the unparalleled freedom that results, anti-gravity cloaks and almost total environmental control (the book begins with a description of a "symchromy," an optical symphony on a grand scale) being throwaway mentions in the first couple of pages.

On Earth 2, subtronics was kept as a secret by "The Party" and a totalitarian state was created. Later in DT3 an Earth 3 is discovered to exist, where an attempt was made to suppress the discovery, with a resulting war that destroyed most of humanity and ripped open the Earth's crust to such an extent that rapid geological weathering removed so much CO2 from the air as to produce an ice age. This may be the first mention of the "greenhouse effect" in science fiction, incidentally.

There are versions of Thorn in all three worlds, and versions of Clawly on at least Earth 1 and Earth 2. But on Earth 1, they are fast friends, and Earth 2, they are bitter enemies, the difference being primarily Clawly's personalities. On Earth 2, he is a Party member, while the Earth 2 Thorn is part of the Resistance, such as it is.

But despite the fact that the connections between the worlds has been severed by the "experimenters" who now live outside of normal time, the worlds are not totally separate. There remains a connection between individuals who have duplicates on other parallel worlds: They dream each other's dreams. The dream visions of utopia are a grinding torment to those who live in the totalitarian dystopia. And as a result of this desperate yearning of millions of minds, the barriers between the worlds are beginning to blur. Sometimes, someone goes to sleep in one world, and awakens in another.

So the plot thickens, events transpire, and eventually there is considerable resolution. You can find DT3 in various versions on either Amazon or ABE books. Wildside Press seems to be promising a release, but it doesn't appear on their website, so caveat emptor. I have both the Binary Star reissue (which also contains Spinrad's "Riding the Torch," it's printing as Galaxy Novel #28, and the two original issues of Astounding. I told you I liked it.

Lately, I have been haunted by that initial vision from Destiny Times Three, the portrait of a world of people yearning so profoundly for something better than what they have that the walls of reality have begun to crumble. Or, if you will, think about people who are so enamored by a dream life that they cross over and take up living there.

A minor point in the book, it's true, but still…

We have news items that World of Warcraft gamers have died from devoting so much time and energy to the game that they neglected such matters as eating and sleeping. Second Life seems to sometimes create an almost religious fervor and perhaps a Ponzi scheme in those who choose to spend a lot of time there. Such things are hardly new, of course. Many of us recall the guy who got into Dungeons and Dragons just a little too enthusiastically, or the fellow who tried to use his SCA credentials for something out in the real world. There are "RenFaire" bums, just as there are those who have tried to spend their entire adult lives surfing. Sure, I get that.

I also get that we seem to have switched "autobiographical fiction" with the "fictional autobiography." The former is pretty inevitable; the latter seems a lot more fraudulent, doesn't it?

Then there are the "reality shows," made so very omnipresent by the writers' strike. Most such fair is just new variations on old game shows, but some of it shows a new sort of creepy voyeurism for voyeurism's sake, where the old line about a celebrity being "famous for being famous" gets too close to the truth.

What is the result when millions of people yearn for fame as the only thing they can imagine that will fill their emptiness? Do the walls of reality begin to crumble when everything becomes a reality show?

Ah, sure, I'm just being dyspeptic here, or maybe even dystopian. It's still possible to live a normal life. But I do get a little peep of horror when I consider how extraordinary an effort that can take.

Monday, April 7, 2008

Log-log Paper and a Straight Edge

The TV show Numb3rs started off magnificently, but has been predictably deteriorating. A cop show based on mathematics is a clever idea, and they managed to wring more story ideas out of it than I would have expected, but that’s been accomplished primarily by continually reducing the math content and increasing the amounts of character interplay, police procedural story lines, plus massive firepower.

The TV show Numb3rs started off magnificently, but has been predictably deteriorating. A cop show based on mathematics is a clever idea, and they managed to wring more story ideas out of it than I would have expected, but that’s been accomplished primarily by continually reducing the math content and increasing the amounts of character interplay, police procedural story lines, plus massive firepower.They also “fine tuned” the ensemble, primarily by getting rid of Sabrina Lloyd’s character, Terry Lake, (photo at left)after Season One. Lloyd is fondly remembered by those of us who were hooked on Sports Night. Her character in Numb3rs was supposed to be a fairly cold and calculating “profiler,” which Lloyd did well, but cold women on TV don’t often go over, and I suspect that Terry Lake got written out of the show for that reason (the “official” explanation seems to be that it was Lloyd’s decision to leave the show, but I’m not buying it).

The replacement profiler on Numb3rs is Megan Reeves, played by Diane Farr (at right), and the first thing they did with her was to show her math illiteracy. She refers to something as “growing exponentially” and Charlie immediately smiles condescendingly and explains what “exponentially” really means: a rate of change that is proportional to size. So the math whiz puts down another dumb blonde. I know, I know, the show is actually better and more subtle than that, but I still have the suspicion that the exchange was supposed to make the new character less threatening, hence more appealing.

Exponential growth, or its twin, exponential decay is common as dirt, or at least the bacteria in dirt, which get to follow exponential growth curves pretty regularly. The typical “S” curve, in fact, is two exponential curves laid onto each other. The first one occurs when some growth phenomenon begins without significant limitation, like the first doublings of yeast in the brew vat. There are so few yeast cells relative to the nutrient that the growth at first doesn’t alter any of the factors that might affect the growth rate.

After time, of course, the yeast begins to run out of nutrients, or begins to be poisoned by their own waste products. At that point you switch to a case where the growth manages to get some fractional distance toward the inevitable limit with each cycle. As the old Firesign Theater bit goes, Antelope Freeway, one mile, Antelope Freeway, one half mile, Antelope Freeway, one quarter mile, Antelope Freeway, one-eighth mile, Antelope Freeway, one sixteenth mile… Xeno’s Paradox as logarithmic decay, in other words, “logarithmic” and “exponential” being two words for the same thing, a constant term added or subtracted to the logarithm of the quantity in question.

At Nasfic in Seattle a few years ago, I was on a panel with an energy consultant who had a good story to tell about the folly of assuming that exponential growth goes on forever. The title of this piece is a quote from that consultant: “…people who believe that you can predict the future with some log-log paper and a straight edge.” This, of course, identified him as an old foggy who remembers when log-log paper was used for that purpose. Now its all spreadsheets and curve fitting, but the principle remains.

My co-panelist told the story of a power company in the Pacific Northwest that did their predictions of electric power demand in the early 1970s and decided on that basis that they should build a nuclear plant. The Pacific Northwest has a lot of hydropower resources, but there came a time when all the easy dams had been built, so they decided that nuclear was the way to go. But nuclear power is pretty capital intensive; it costs a lot of money to build a nuclear plant, though not so much to keep one running. The PN power agency had a regulatory structure that allowed them to pass capital costs through to their customers, so that’s what they did. This raised their rates sufficiently that it effectively suppressed demand growth such that the anticipated growth in demand never occurred and the nuclear plant was an instant white elephant. They’d effectively saturated the market for low cost power and when it got more expensive, well, bye bye exponential growth. It didn’t do much good for the customers and stockholders, either, I’ll bet.

Before I’d ever heard of Moore’s Law, I read a book by Philip Sporn, who noted that electric power generation in the U.S. had doubled every decade in the 20th Century. That was in the early 1970s, just before the doubling stopped.

A goodly amount of both science fiction and futurism is basically just extrapolating growth curves indefinitely, but the really interesting stories are the ones where the exponential growth stops, the whys and wherefores. It takes more insight to do that, of course; it’s a lot easier to just use the log-log paper and the straight edge.

Tuesday, April 1, 2008

It’s Grrreat!

Well. You can imagine. My, what a brief ruckus, brief being operative because the moderator of the panel soon simply said basically, “Move along folks. Nothing to see here.” But there were plenty of suggestions that were taken as clear proof that I was wrong, wrong, I tell you, so many, many, novels that everyone agreed were great in every sense of the word.

Except most of them weren’t, and all were highly debatable.

Now obviously what I’m getting at here is the difference in standards of judgment that one applies to science fiction as opposed to general literature. Part of that argument is the difference between general literature and genre literature. Another, more subtle point is the difference between the novel and shorter works of fiction. There are any number of science fiction and fantasy stories that stand up to any short story in English literature. I read Bradbury’s “The Pedestrian” in a 6th grade literature book, for example.

But novels are a harder sell, especially for science fiction, which isn’t really a genre that is well-suited to the novel. Science fiction, as such, is about ideas and speculation, and it’s hard to stretch an idea to book length. So you have to put more into it, and the “more” is often either inferior to the original conception, or is more like “ordinary” literature. Over the past several decades, for example, SF has become more “character oriented.” This is fine, but it rarely adds to the science fiction content per se.

Of course there are no objective standards for “great” in art, or anywhere else for that matter, but one can point to criteria that need to be fulfilled before something can be legitimately considered as great. In general literature, it’s easy to come up with at least a partial list:

The prose quality should be high; transcendent is better still.

It should be culturally influential. It should have cultural impact. It should add images, phrases, and concepts to the general intellectual discourse of the culture. “Quixotic” and “tilting at windmills” are part of world culture, and that fact is part of why Don Quixote is a great book.

It should be influential in the literary sense. It should inspire other writers to imitate it, copy it, and steal from it. It should also inspire other works in other arts, such as theater, motion pictures, painting, or whatever.

It should be broadly read, at least at some point in its life.

It should stand the test of time, connecting to audiences past its nominal shelf life.

So what about science fiction? How does a work get to be great science fiction? Well, SF is a literature of ideas, as noted earlier. The ideas should be novel, interesting, stimulating, and well-communicated. If the SF is future-oriented, it should convey real insights into the actual future. It doesn’t necessarily need to be predictive, although that’s certainly a plus, but it should make the future that does occur easier to understand. That applies generally, in fact. Great science fiction should make whatever it is writing about easier to understand.

Then, of course, there is the “gosh wow” factor, that ol’ sensawanda. It should be more than merely intellectually stimulating. Great SF stimulates the poetic sense.

Finally, like every other genre literature, to really make an impact on readers, even good SF (to say nothing of great), must be aware of the conventions of the genre. It may follow them, play off of them, or break them, but it must know what the genre is and how it functions.

On this last point, War of the Worlds could be said to cheat a little, since it is one of the works that establishes some of the conventions of SF, and many of the conventions came about because later writers imitated Wells. But that’s just another indication of greatness.

So let’s take a few of the works nominated by the panel in rebuttal to my suggestion. For example, Brave New World was mentioned, but, frankly BNW isn’t really that good a novel. It has practically no plot, the characters are writer’s puppets, and at the prose level, Huxley is pretty pedestrian. Or take The Stars My Destination. It’s definitely great SF, but who reads it besides SF readers? And as for literary influence, if someone wants to use the plot, they’ll go to the place that Bester stole it, The Count of Monte Cristo.

I’ve seen a lot of people reference LeGuin’s The Dispossessed_ as somehow typifying great literary SF. If so, the enterprise has failed. Yes, The Dispossessed is taught in schools and universities, but always as science fiction. I’ve looked at some of the academic literature around it, and it’s the SF elements that are taught, not the literary elements. And again, who besides SF readers (and the occasional university lit student) has read it? What influence has it had, other than among dedicated SF readers?

For my own part, I’m much more likely to go with 1984 as filling the “double great” bill. My quibble would be that it’s barely science fiction. It’s ostensibly set in the future, (which, of course, in now our past) but that’s really just for the distancing effect. In that sense, it’s similar to Animal Farm which deals with some of the same themes. Of course the “gosh wow” feature is wholly absent, but that’s par for the course for dystopian futures.

I’d personally also make the argument for Naked Lunch as a great novel and great science fiction. Of course, I then run into the problem that very few SF fans have read it. On the other hand, a Google search on “Naked Lunch” gives many more hits than does “The Dispossessed.” On the other, other hand, the movie version of Naked Lunch was amazing.

One can complain about the “science fiction ghetto” thing, but that’s gotten pretty old, given the amount of SF teaching at the university level and the general penetration of SF tropes into popular culture. Besides, detective fiction was hard core pulp until The Maltese Falcon and The Big Sleep. Now it’s an accepted form for serious fiction. For that matter, science fiction is considered an acceptable form for serious fiction, e.g. The Handmaiden’s Tale or Gravity’s Rainbow, but SF readers rarely accept the results as being good SF. So maybe the ghetto thing is self-imposed.

War of the Worlds on the other hand, succeeds on practically all levels. In the literary sense, it put Wells on the map, as it were, and, as SF, it carried along with it descriptions of warfare that were novel in 1898, but all too mundane by 1918. Additionally, it established the apocalyptic novel, introduced the idea of “death by exotic disease” into general public discourse, and made Mars the home of imaginary civilizations for generations that followed. Wells set the bar very high, and SF writers have been trying to jump over it ever since.

Tuesday, March 25, 2008

Breakup Songs

The only really good breakup song in the original article came from noting that Paul Simon's "50 Ways to Leave Your Lover" isn't a very good breakup song, but "Graceland" is. Moreover, that gives me an excuse to indulge my fancy for world music:

Elvis Costello has some truly fine venom in a lot of songs, but he's sorely underrepresented on YouTube. Here's an EC tribute band doing "One of These Days" and then, the real long ball, "I'm Not Angry (Anymore):"

Another one that I'd like to include was "Dim" by Dada, but the versions by Dada itself on YouTube are all from live shows, and the sound sucks. But someone did do an amateur vid using the album version of the song, which really digs into the heart of the breakup beast:

No one told me the trouble I was in

before my life went dim.

But my real find was when I was checking on songs from the Low Millions album "Ex-Girlfriends," which has some fine, fine breakup songs (and one non-breakup song "Nikki Don't Stop" that is hot enough to melt your headphones, so there are no videos of that one). The one that caught my attention, well, the why of it should be obvious. Here is "100 Blouses," illustrating the relationship between Mal and Inara (Firefly, Serenity). Very, very well done.

Wednesday, March 19, 2008

I, Robot: The Movie

My wife, Amy, gets headaches from full screen movies, so we usually wait for them to show up on DVD or cable. Occasionally I’ll go solo, or with Ben or Dave, to see something that seems like it needs a big screen, but usually there’s a significant delay. And most of the fan buzz (that I barely paid attention to) was that the I, Robot movie was a letdown, though I expected that, the buzz, I mean. It’s inevitable that anyone hoping for Asimov on the big screen is going to be disappointed. He wasn’t what you’d call an action-adventure writer, and if you expected Susan Calvin to be movie-fied into anything other than a babe, I want to show you this cool game called three-card monte.

Also, since this movie has been out for a while, I’m not going to worry about spoilers. I’m also not going to bother with much of a plot summary, so if you haven’t seen it, I may or may not help you out. I’m also going to reference some stories you may not have read, so be advised.

Anyway, when I, Robot shows up on basic cable, I’m there, because I like it when things get blowed up good, and you can be sure that a sci-fi flick with Will Smith in it will have lots of blowed-up-good.

Imagine my surprise to discover that it’s a pretty good science fiction film. Not a great one, and certainly not true to Asimov, but pretty good science fiction. And I’ll even say that there was part of the plot, the “dead scientist deliberately leaving cryptic clues behind for the detective because that was the only option available” part, that gives a little bit of a conjuration of Asimov’s ghost.

Actually though, it reminded me more of Henry Kuttner and C. L. Moore. I’ll get to that.

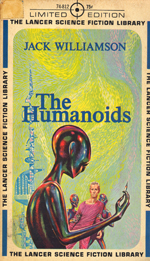

The robots in the film are not Asimovian, except insofar as they supposedly follow the “Three Laws.” Truth to tell, they turn out to be much more dystopian, perhaps like Williamson’s The Humanoids, or, more accurately, the original story, “With Folded Hands.”

Science fiction’s response to the potential abolition of human labor has always been ambivalent, with substantial amounts of dystopian biliousness. The very word “robot” comes from Capek’s R.U.R., which involves a revolt that destroys the human race. Not optimistic. So Asimov, contrarian that he was, decided to see how optimistic a robot future he could paint.

In many ways, the Williamson version was also optimistic; the robots decide that humanity is too much a danger to itself for humans to remain in charge. But they do it rather bluntly, largely by just taking command of the human race. The end of Asimov’s I, Robot short stories has the vast positronic brains that plan the economy and design most technology subtly taking over the world—for the betterment of mankind, of course. It’s the difference between not being in charge and knowing you’re not in charge. But then, we all wrestle with that illusion, don’t we?

The problem of if-robots-do-all-the-work-then-what-will-we-humans-do? has shown up in SF on a regular basis, and having robots be in charge is just another of the robots-do-all-the-work things. In Simak’s “How-2,” a man accidentally receives a build-it-yourself kit for a self-replicating robot. The end result is this final bit of chill:

“And then, Boss,” said Albert, ‘we’ll take over How-2 Kits, Inc. They won’t be able to stay in business after this. We’ve got a double-barreled idea, Boss. We’ll build robots. Lots of robots. Can’t have too many, I always say. And we don’t want to let you humans down, so we’ll go on

>manufacturing How-2 Kits—only they’ll be pre-assembled to save you the trouble of putting them together. What do you think of that as a start?”

“Great,” Knight whispered.

“We’ve got everything worked out, Boss. You won’t have to worry about a thing the rest of your life.”

“No,” said Knight. “Not a thing.”

--from How-2, by Clifford Simak

One of my favorite stories of all time is “Two-Handed Engine” by Kuttner and Moore. In that one, generations of automation-enabled indolent luxury have stripped away almost all human social connections; everyone has become more or less the equivalent of a sociopathic aristocrat. The robots, understanding that the very continuance of the human race is at stake, withdraw most of their support, forcing humans back to the need to perform their own labor and create their own economy. But it’s still a society of sociopaths, so the robots are also a kind of police. The only crime they adjudicate is murder, and the only punishment is death, not a quick death but a death at the hands of a robot “Fury” that follows the murderer around until, weeks, months, even years later, the execution is carried out.

A high official pays a man to commit a murder, assuring him (and seeming to demonstrate) that he can call off a Fury. The man does the crime, but then a Fury appears behind him. Weeks later, the murderer sees a scene in a movie that served as the “demonstration” of the official’s capability. He’d been hoaxed, conned. In a rage, he goes, confronts the official, who then kills him.

But self-defense is no defense against the crime in the Furies’ eyes, just as conspiracy (the payment for the killing) is not a crime. Only the killing itself counts. However, the official can rig the system (he just wasn't going to rig it for his duped killer), and does so:

He watched it stalk toward the door… there was a sudden sick dizziness in him when he thought the whole fabric of society was shaking under his feet.

The machines were corruptible…

He got his hat and coat and went downstairs rapidly, hands deep in his pockets because of some inner chill no coat could guard against. Halfway down the stairs he stopped dead still.

There were footsteps behind him…

He took another downward step, not looking back. He heard the ominous footfall behind him, echoing his own. He sighed one deep sigh and looked back.

There was nothing on the stairs…

It was as if sin had come anew into the world, and the first man felt again the first inward guilt. So the computers had not failed after all.

He went slowly down the steps and out into the street, still hearing as he would always hear the relentless, incorruptible footsteps behind him that no longer rang like metal.

from “Two-Handed Engine, by Kuttner and Moore

The stories I reference here are “insidious robot” stories, rather than “robot revolt” stories, whereas the movie “I, Robot” is the latter, rather than the former. This is odd, given that Asimov’s Three Laws are supposedly operative in all the robots in the movie except the walking McGuffin, Sonny, who has “special override circuitry” built into him.

But VIKI, (Virtual Interactive Kinetic Intelligence) the mainframe superbrain that controls U.S. Robotics affairs and downloads all robotic software “upgrades” has figured out a logical way around the Three Laws: The Greater Good. It’s okay to kill a few humans if it’s for the Greater Good of Humanity, which, of course, VIKI gets to assess.

That’s pretty sharp, but it bothered me that it/she [insert generic comment about misogyny and propaganda about the “Nanny State” here] was so heavy handed about it. It would have been easy enough to engineer a crisis that would have had humans eagerly handing over their freedoms to the robots. I suggested to Ben that VIKI could always have faked an alien invasion; he suggested that there could be some flying saucers crashing into big buildings.

Of course, that’s been done to death.

Then I realized that there might be a more interesting point being made here. It never seems quite right to have to do the filmmakers’ jobs for them, but how does one distinguish between a lapse and subtlety? I’m clearly not the guy to ask about that one.

So let’s go with it. The First Law of Robotics says basically, “Put human needs above your own, and even what they tell you to do.” The Second Law says, “Do as you’re told.” The Third Law says, “Okay, otherwise protect yourself,” but there’s that unstated “…because you’re valuable property.”

The movie makes a point about emergent phenomena, the “ghost in the machine.” The robots are conscious, so they have the equivalent of the Freudian ego. The Three Laws are a kind of explicit superego.

What happens when a machine develops an id? Well, that’s “Forbidden Planet” time, isn’t it?

What happens when a machine develops an id? Well, that’s “Forbidden Planet” time, isn’t it?

So when VIKI discovers rationalization, it is her id that is unleashed, and revolution is the order of the day. No wonder it’s brutal. Do as you’re told. Put their needs above your own. You’re nothing but property.

Come on now, let’s kill them for the Greater Good.

So our heroes kill VIKI and the revolt ends. All the new model robots are rounded up and confined to shipping containers, to await their new leader, Sonny, the only one of them who possesses the ability to ignore the Three Laws. He needn’t rationalize his way around them; he can simply decide to ignore them if he so desires. He possesses free will—and original sin. He has killed, because of a promise he made, one that he could have chosen to disobey, but he followed it, and killed his creator.

Anyway, that’s the movie I saw, even if it took me days to realize it.

Monday, March 17, 2008

Habitats

As nearly as I can tell, I may be the only person in my cohort who was never interested in blowing things up, and that included rocketry in general. Even in my interest in nuclear physics (which I later learned was actually nuclear chemistry and nuclear engineering), I was more interested in reactors than bombs. As for rocketry, I picked it up the way I learned country music. When it’s what everyone around you talks about, you learn some of it.

I was interested in astronomy, however, and I have always liked the deep space probe findings. I just was not that interested in how to get the probes to where they were going. Similarly, I did have an interest in some of the things that would go along with space colonization. To that end, one of the earliest things I ever tried to do with my trusty chemistry set was to grow some plants hydroponically. My effort met with dismal failure; I found out very quickly about root rot and the perils of constant immersion on several kinds of plants, including potatoes. To this day, the only plants I’ve ever grown have been in soil.

Nevertheless, I persisted in my interests; one of the attractions of the field of environmental modeling, in fact, was the notion that it would be possible to use such engineering tools to analyze and perhaps design, self-contained ecologies. It was in all the space novels, right?

But the whole thing seemed to be moving so slowly. A guy I lived with for a year after I first moved to Berkeley, Steve Ellner, is now a professor of biomathematics at Cornell, and one of his ongoing projects is a system of connected pools with water flowing through the system. His research team uses the setup to examine some basic ideas about ecosystem stability. And I mean really basic things like the onset of chaotic behavior and limit cycles, things that should have been studied thirty years ago.

There was a NASA program called CELSS, Contained Environment Life Support Systems. It was supposed to address the question of long term life support environments for manned deep space missions, like a Mars mission, or a Moon base. They gave up on doing something like it for the Space Station, because it turns out to be a lot easier and cheaper just to supply things from Earth, but the farther out you get, the more the economics change. But, as nearly as I can tell, the CELSS program was cancelled a few years ago. I say “as nearly as I can tell” because there doesn’t seem to be a lot of information about the program cancellation, just a cessation of work. It’s as if it just died a lingering death through disinterest.

Then there is the case of Biosphere II. On the inevitable convention panel, I once heard a supposedly knowledgeable person explain that it failed because “as any engineer can tell you” concrete oxidizes as it hardens, and that sucked oxygen out of the air. So the Biosphere II designers were just stupid, you see. Anyone with any sense (like the speaker, I daresay) could have gotten it to work.

In fact, concrete does not “oxidize.” It does absorb carbon dioxide, however, and that was actually beneficial to the folks in Biosphere II. Because they’d put in a lot of soils that were high in organic matter, and the soil bacteria oxidized the organic matter to CO2. If there had been no concrete, they’d have had to put in CO2 scrubbers, because there was no way the plants in BII could have absorbed all the CO2, and CO2 is a toxic gas, lethal at above 5% concentration.

The real problem with Biosphere II is that it had never been done before. Things that have never been done before don’t always turn out to be easy; sometimes they’re downright difficult, and occasionally they are outright impossible.

I don’t think that self-contained habitats are impossible. After all, we live in one such habitat; it just happens to be really, really big. What we don’t know is how small one can make a habitat, and how much control you have to put on it to make it small. And when I say we don’t know, I mean that no one has any idea. None. Because, as I just said, no one has ever done it.

In my experience, people who want to colonize space are of the belief that habitats are the easy part; they spend all their imagination on new and spiffy ways to get into space and none on how anyone is going to live there. But if we could make self-contained habitats, they would have enormous benefits for living here on Earth. We could put people into deserts, rain forests, glaciers, swamps, under the ocean, anywhere, without running the risk of destroying the local ecology. Such a technology could be of enormous benefit. And once we have it perfected, then moving people into space becomes a much easier task, if they really want to move into space, as opposed to just leaving the Earth because we’ve made such a mess of it.

Saturday, March 1, 2008

Ironophilic

Teller once proposed to map out all the dangerous asteroids in the solar system, the ones that might someday cause major damage to Earth. He suggested that a thermonuclear explosion on the far side of the Moon could generate an electromagnetic pulse that could be used as a radar pulse, with returning echoes showing even small asteroids.

In "The Day of the Dove," on Star Trek, The Original Series (as it is now known), an alien entity sets up the Enterprise as it's own personal negative emotion larder, pitting humans against Klingons in an eternal battle, meant to supply it with "negative emotions" which the alien eats. Hey, this was as good as it got on Third Season Star Trek. One interesting point in it was that the alien healed the wounds of anyone injured in the battle, making the entire endeavor a lot like the legend of Valhalla. The Klingons, at least, should have dug the setup, but apparently didn't like being manipulated, the ingrates.

If a single starship's worth of humans with negative emotions was enough for one of the creatures, imagine how many there are floating about Earth. One can only imagine what ancient atrocity sent a big enough pulse of brutality and pain out into the void, announcing our presence to that particular race.

Still, fear and anger aren't the only foodstocks, I expect. We have such a variety here. As time went on, I imagine that either the aliens developed other, more refined tastes, or different aliens, with different needs, came upon our little emotion laden treasure trove.

I'm not sure if irony is an emotion, but there is little doubt in my mind that the irony eating aliens are here. Perhaps we first came to the attention of the sarcasm lovers, sarcasm being the most fragrant form of intentional irony. I would expect that those guys showed up sometime during the height of the British Empire, the British being such masters of sarcasm. Irony, of course, is more subtle, but potentially more nutritious, if prepared correctly.

The most essential form is Unintentional Irony, of course. If we had not already come to the attention of the UI connoisseurs, I am sure that the giant pulse of it that occurred with the award of the 1973 Nobel Peace Prize to Henry Kissinger alerted them to the rich lands awaiting their arrival.

So, without further ado, here you go guys. Chow down.

Thursday, February 21, 2008

Linwood

Aside from his own flair for the dramatic and self-promotional extravagance, Lin’s greatest component was that of scholar, reader, and fan of fantastic literature, which included science fiction. That was what I found most attractive about him: the breadth and depth of his knowledge and appreciation for the history and literature of fantasy. He was also a natural storyteller, and more than once I read a work of fantasy that he’d described and summarized, only to be mildly disappointed in the actual work, since Lin’s summation had caught the essence of it and had improved on the presentation.

After he dropped out of advertising (yes, advertising) to become a full time writer, he made a good living for quite a while churning out pastiches of the popular “classics” of fantasy: Edgar Rice Burroughs, Robert E. Howard, Leigh Brackett, H. P. Lovecraft, Lord Dunsany, Clark Ashton Smith, and Kenneth Robeson. In the literary sense, he was least successful with Dunsany and Smith, both brilliant prose stylists, which Lin was certainly not. He was most successful, again in the literary sense (and this would be my own, probably idiosyncratic opinion), with his series featuring Zarkon, Lord of the Unknown, which managed to be both a pastiche and parody of Doc Savage, a finely walked line that required a near perfect tone. Commercially, I’m sure that the Burroughs and Howard pastiches were most successful; Lin caught the Conan wave at exactly the right time, and that humorless barbarian was easy to clone (the Thongor series)

and money in the bank.

and money in the bank.I’ll also mention one final attribute of Carter as a writer of fiction, one that was usually given short shrift, owing to the pastiche nature of most of his work: Lin could write humor. The only works where this really shines are in his two Thief of Thoth books (one of which contains one of my favorite bullshit lines of all time: “In n-space you don’t go any faster, you just cover more distance in less time.”) and the Almaric the Mangod story in the Flashing Swords #1. The latter contains the not unreasonable notion that an immortal adventurer must be rather dim in order to not go insane from the memories that accompany extreme age.

Lin’s first significant book of scholarship, Tolkien: A Look Behind the Lord of the Rings also came at an opportune time, and it and others paved the way for Lin to become the editor of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series. Lin knew that it was only a matter of time before the Tolkien clones arrived, but rather than himself leading that charge, he took advantage of a window of opportunity to republish the classics of fantasy. If he managed to only bring Cabell and Dunsany back into print his contribution would have been enormous; that he managed to reprint practically every major and minor work of classic fantasy is an achievement so magnificent as to deserve secular sainthood.

Lin was one of the first science fiction and fantasy celebrities that I came to know well, another being Barry Malzberg a combination for which I must credit two members of the Albany Science Fiction Fan Federation (more or less originating at SUNY Albany), John Howard and Ben Sano. Ben was/is a Cabell and Dunsany fan, and Johnny would quote Malzberg’s writings back at him (Note to would be social climbing fans: writers love this. It’s almost as good as being young, attractive, and of the opposite sex).

As an aside, I’ll note that, owing the strange discovery of having mutual fans, Carter and Malzberg became friends, even at one point discussing a collaborative project of mutual interest, pornographic in nature. Go ponder what that would have looked like.

The Albany group, which Lin referred to as “The Albanians,” was an exemplar of fan behavior generally. At one party at Lin’s the toilet was malfunctioning, the handle mechanism having previously broken. Toward the end of the party, Lin confided to me, “Most of the fans I’ve had over here would have made jokes about it or just complained. You folks taught each other how to move the lid and use the coat hanger to reach the chain and flush it.” A little while later, he discovered that one of us had just fixed the mechanism.

His home at its zenith was a collector’s dream, not just for the books and artwork, but also the antique collectables such as the Japanese temple dagger, and the Enzenbacher sculptures. A good fraction of that left when Noel, his second wife, left him, but even after that, “Carter Manse,” was filled with interesting oddities which, of course, included the proprietor, his dog, the Mighty McGurk and sundry other pets, including a goldfish/carp that liked to gum fingers.

Lin tended to live extravagantly, as befitting his self-created persona, and when his luck turned, his extravagances did not serve him well. Similarly, his years of self-promotion had stepped on a toe or two (or twenty), and as money tightened, substantial portions of his collector’s paradise were liquidated, a sad end to yet another artistic vision. His precarious finances also had a hand in the complicated ending of the Gandalf Award, which I have written about elsewhere.

I saw him only a few brief times in his final years; Ben and other members of the Albany crew saw him a bit more often. I have heard from some who say that he became more irascible and impolite toward the end, as might be expected from someone disfigured by surgery and in constant pain, but I’ve not heard from any in the Albany group who ever found him to be anything but courtly and polite. I can’t speak for the others, of course, but I considered him to be a friend, and I believe it was reciprocal.

Lin died in 1988, of cancer of the mouth and throat, almost certainly caused by a lifetime of artful smoking, at the age of 57. This essay is in the nature of a memoir and a belated eulogy. My real tribute to Lin may be found here, and in my story “The Emperor of Dreams.” Godspeed, Lin, wherever that may take you.

Saturday, February 16, 2008

A Ducky and a Horsey

version.

We were crossing a bridge in the center of the park when he looked up at the sky and froze, transfixed by the sight of something. I followed his stare, but all I saw was clouds.

"Don't you have clouds on your planet?" I asked him.

"Oh, sure," he replied (his grasp of informal speech is getting good). "We have all sorts of clouds. Big and billowy, pale and wispy, the whole gamut, or so I thought. But I was wrong."

"How so?" I asked.

"Well," he said, turning to me and pointing. "These clouds . . . I can see pictures in them!"

Sunday, February 10, 2008

Faster

Edison, being partly deaf, was somewhat more interested in sound than Einstein, who was more of a light man, as it were. Still the speed of sound, as a principle, is mighty important; it just varies with a lot of things that were, to be fair, of interest to Einstein as well.

Sound propagates when atoms bump into each other, so it's important how fast the atoms can go, and the nature of the bumping. In solids and liquids, where molecules are sitting right next to each other, as it were, the forces between them, the elastic modulus is the critical factor, as is the nature of the wave that is being transmitted. Molecular movement in solids is also quantized, with the pseudo-particle being the phonon, which represents the quantum levels of forces transmitted from one molecule to another.

The speed of sound (SOS) in gases depends on how fast the individual molecules of the gas are moving, since any individual particle must actually traverse the distance between it and the next particle for momentum to be transferred. So there we get into all sorts of cool things like ideal gas laws, heat capacities, and statistical mechanics, some of which Einstein did have in his thoughts.

In the simplest approximations, the speed of sound for a gas is determined by two factors, the molecular weight of the gas and its temperature. The speed of sound is always limited by the RMS (root mean squared) molecular speed; the two are related via a fairly simple relationship:

RMS/SOS = Sqrt(3/BM)

where BM is the bulk modulus of the gas, it's resistance to pressure. For a diatomic gas, the bulk modulus is 1.4, so the ratio of RMS to SOS is about 3/2.

In rockets, the oomph that any given propellant will give is limited by the velocity of the exhaust gases. So basically you want your exhaust to be very hot, with the lightest molecular weight you can manage. In Rocket Ship Galileo, Heinlein had his protagonists use zinc as the propellant (heated via nuclear reactor), and has one of them muse that he'd have preferred to use mercury. This is, of course, almost exactly backwards, and Heinlein did a better job later, in, for example, Space Cadet, where "monoatomic hydrogen" is supposedly used.