In fact, my copy of complete Grimm tales I use mainly for reference. I find it helpful to discover books in which tales are separated by categories such as themes or country of origin, which is why I was pleased to discover Grimm's Grimmest, edited by Marisa Bulzone, in my library. Not only did it introduce me to several tales I wasn't as familiar with alongside some of the classics, but the best part was the introduction by Maria Tatar.

She provides a little history of the Grimms and their process of collecting but also editing the tales to suit, what was then, modern tastes. Although the Grimms (and the general culture of the time) abhorred any mention of sexuality or pregnancy, altering the tales to remove such references, they actually tended to increase the violence when it was part of a character's punishment. Seemingly shocking and harsh punishments for what we might consider to be small misdemeanors were characteristic of not only the Grimms' collection but other children's literature of the time, such as Strewwelpeter.

Page from the book-Illustrations by Tracy Arah Dockray

For example, the short and haunting story "The Willful Child" would have been more or less typical fare for the time:

Once upon a time there was a child who was willful and would not do what her* mother wished. For this reason, God had no pleasure in her, and let her become ill. No doctor could do her any good, and in a short time the child lay on her deathbed.

When she had been lowered into her grave, and the earth was spread over her, all at once her little arm came out again and reached upward. And when they had pushed it back in the ground and spread fresh earth over it, it was all to no purpose, for the arm always came out again.

Then the mother herself was obliged to go to the grave and strike the arm with a rod. When she had done that, the arm was drawn in, and at last the child had rest beneath the ground.

*In the introduction, Tatar clarifies that in the German, the child is given no specific gender

Tatar also cited psychology and the fact that "children are rarely squeamish when they hear about decapitation or other forms of mutilation. Typical Saturday morning cartoon fare shows that grisly episodes often strike them as hilarious rather than horrifying." It's true that some of the stories, even with their gruesome aspects, I found mostly entertaining, such as "The Three Army Surgeons." Yet others were truly hard to read-I don't think anyone can read "The Willful Child" above and not find it disturbing on some level (and this collection didn't even include "How Children Played Butcher with Each Other," which I find the most horrifying).

For while we tend to think of fairy tales as simple, sweet children's stories, Tatar reminds us that they are also the precursors to other genres, such as urban legends and horror.

Yet, there are different categories when we look at violence in tales. There is violence that is punishment for a truly horrible villain-which we tend to be more comfortable with; children in America are familiar with the scene in which Gretel pushes the witch into the oven, whereas we have largely forgotten some tales that are still part of general knowledge in Germany today, such as "Juniper Tree" which involves a mother decapitating her son and feeding his flesh to her unknowing husband (and, another perfect example of cultural differences in approaching fairy tales!).

Tracy Arah Dockray-illustration for "Juniper Tree"

Then, sometimes, the protagonist is treated cruelly by the villain. This elicits sympathy from the reader and further establishes which characters we're rooting for and which ones we're against, and many of our most loved heroines in American culture fit into this category-Snow White and Cinderella, for example.

Then there's a different sort of story in which the violence doesn't seem to serve a purpose at all. In tales like "The Death of the Little Hen," the stories lead from one tragedy to another, with no happy ending. They seem pointless and depressing, but Tatar reminds us that if nothing else, these tales point to the harsh cruelties of peasant existence, where diseases spread rampant, mothers often died in childbirth, and poor harvest meant going truly hungry. Fairy tales blend truth with hope. Although the common perception is that fairy tales are all hope and no truth, that's a misconception; but it would also be misleading to present all Grimm tales as the creepy, depressing ones found in this volume either. We can point to the darker aspects of fairy tales but they are not the complete picture.

Albert Weisgerber-"The Death of the Little Red Hen"

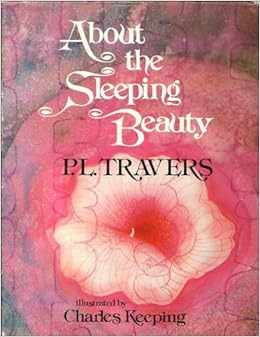

I have to point out though-I was very disappointed that the book jacket description claims that the Grimms' "Aschenputtel" was "the original Cinderella story." It's a common thing to mistake Grimm tales for "original," but for someone responsible for creating a book description to make such a gross error, especially when Perrault's version is not only older, but arguably more famous? Whoever wrote it clearly didn't read Tatar's introduction, which not only referenced Perrault's "Cinderella" (with the year, 1697), but compared and contrasted the Grimms' version with Cinderella tales from around the world-some of which show forgiveness for the stepsisters and some of which are incredibly violent in their punishments. On the one hand this shows that violence is not limited to German or Grimm tales, but on the other it shows that violent aspects are not necessary for the tale type.