The Punctual Rape of Every Blesséd Day

Writing about Cathy Seipp’s death yesterday on Gates of Vienna has led me to a long meditation on my childhood.

What sparked the ruminations was the clear memory of singing Gregorian chant during the many Requiem Masses we were called out of class to chant during the liturgy. I can’t remember how many of us there were…though since our choir director,Sister Marie Therese, is still alive and more active than I am, I will find out. Back then, it felt as though our numbers filled the choir loft.

Not being very good at it, I was ususally relegated to the alto section. Not much tune in the alto section, but we made up in strength for what we lacked in quality. And I liked the ver plain chant of the alto part. It was soothing.

Which led me to thinking about my less-than-optimum childhood and to wondering why I am not more dysfunctional than I am. What factors “saved” me?

This may sound strange, but I have often wondered if group singing had a great deal to do with soothing the savage breast of so many displaced children. We sang all the time: at church, during recreation time, on bus rides to while away the boredom. I know the old songs from the childhoods of the nuns, the songs of the Big Girls (anyone over ten was a “Big Girl” and was of much higher status than we were). These higher beings rolled their hair in curlers, wore bras, and they sang the latest songs - Nat King Cole comes to mind. They were also in charge of cooking and did a terrible job at it. Perhaps I grew up to become a good cook partly in retaliation for all the mornings of burned oatmeal.

Obviously singing is not enough to get you through [“Hah,” say my Observing Self. Just hum a few lines of “Whistle a Happy Tune”]. The linchpin holding everything together was our unvarying schedule. All these years later, I can still recall how the hours of our days were structured, winter and summer. We lived a cloistered life, punctuated not only by song, but more importantly by prayer. Prayers for getting up, prayers for lying down. Prayers before and after meals. The Angelus at noon. The rosary in the nuns’ chapel after dinner. Prayer was the skeleton on which the flesh of our days hung.

When I grew up and read The Eight Ages of Man, I remember the author saying that what saves childhood for many of us is an over-arching sense of meaning. A few months ago I read his daughter’s story of her father’s life. He invented himself, carved out his own meaning. He never even knew his real last name, so when he moved to this country, he named himself Erik Erikson. And - in an attempt to preserve an identity that was closed to him by his mother’s silence re his beginnings — Erikson resisted his Jewish step-father’s fervent desire for him to adopt Judaism. However, I think the rituals and observances of the religion he refused saved him, too. Erikson’s productivity was unflagging.

And his new identity? An attempt to get past the boundary his mother erected, to find his first Self.

My productivity is more porous than his. I never know, on waking up, if I will be scattered and lack all initiative, or if whatever remains of the inner Mafia of my childhood will permit me to move through the day in relative calm, experiencing the initiative that - in more integrated souls - allows one to stay vertical and busy. I read once that happiness means being busy about eighty or ninety percent of the time. That sounds about right to me. In fact, I lust after the energy required to maintain such a virtuous schedule…and on the days that I do, life is glorious.

Richard Wilbur captured it perfectly in this, my favorite of his poems:

Love Calls Us to the Things of the World

The eyes open to a cry of pulleys,

And spirited from sleep, the astounded soul

Hangs for a moment bodiless and simple

As false dawn.

Outside the open window

The morning air is all awash with angels.

Some are in bed-sheets, some are in blouses,

Some are in smocks: but truly there they are.

Now they are rising together in calm swells

Of halcyon feeling, filling whatever they wear

With the deep joy of their impersonal breathing;

Now they are flying in place, conveying

The terrible speed of their omnipresence, moving

And staying like white water; and now of a sudden

They swoon down into so rapt a quiet

That nobody seems to be there.

The soul shrinks

From all that it is about to remember,

From the punctual rape of every blesséd day,

And cries,

“Oh, let there be nothing on earth but laundry,

Nothing but rosy hands in the rising steam

And clear dances done in the sight of heaven.”

Yet, as the sun acknowledges

With a warm look the world’s hunks and colors,

The soul descends once more in bitter love

To accept the waking body, saying now

In a changed voice as the man yawns and rises,

“Bring them down from their ruddy gallows;

Let there be clean linen for the backs of thieves;

Let lovers go fresh and sweet to be undone,

And the heaviest nuns walk in a pure floating

Of dark habits,

keeping their difficult balance.’

Aside from his ode to laundry - obviously he didn’t wash it or hang it out, nor does he suffer from the "rosy hands" that did so...still, since it billows there outside his window on wakening: he knows, oh he knows:

The soul shrinks

From all that it is about to remember,

From the punctual rape of every blesséd day…

The soul's "bitter love," indeed.

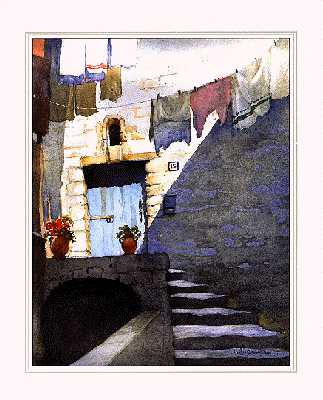

The painting, “Washday” is from a small collection of works by Val Doonican

This is an up-and-down day for me. Already had two teary spells and the day is still young. Well, youngish…the sun is still making its way across the sky.

This is an up-and-down day for me. Already had two teary spells and the day is still young. Well, youngish…the sun is still making its way across the sky. I gingerly climbed the stepladder (ever since I fell off that ladder and shredded the meniscus on my left knee, the Baron gets nervous when I venture near it) and began pruning the old apple tree, removing suckers and branches that crossed through the middle. Its mate died off finally last year – so dead that even the remaining flat stump is a little spongy and rotten. Meanwhile the live one will take a bit of work since I didn’t prune it last year. The light was fading by the time I’d cleared the western side of the tree. I don’t know how much longer it has, either. I think I will replace them both with Arkansas Blacks. That is one fine apple. Or maybe Albemarle Pippins. Now wouldn’t that be a treat?

I gingerly climbed the stepladder (ever since I fell off that ladder and shredded the meniscus on my left knee, the Baron gets nervous when I venture near it) and began pruning the old apple tree, removing suckers and branches that crossed through the middle. Its mate died off finally last year – so dead that even the remaining flat stump is a little spongy and rotten. Meanwhile the live one will take a bit of work since I didn’t prune it last year. The light was fading by the time I’d cleared the western side of the tree. I don’t know how much longer it has, either. I think I will replace them both with Arkansas Blacks. That is one fine apple. Or maybe Albemarle Pippins. Now wouldn’t that be a treat? The daffodils and spring crocus are blooming. Even a couple of hyacinths. The pansies are putting out flowers, but haven’t spread much yet. I see some holes where a few died off during the winter. Will have to fill those soon – I love the antique colors, though some years I’ve done blues and white. And last year I did that strange orange variety. It sure did light up the place. Most of the tulips survived the voles – that trick with Bon Ami in the hole must have worked. It will be weeks before they bloom, though, and then the hostas will come along to cover their straggly ending.

The daffodils and spring crocus are blooming. Even a couple of hyacinths. The pansies are putting out flowers, but haven’t spread much yet. I see some holes where a few died off during the winter. Will have to fill those soon – I love the antique colors, though some years I’ve done blues and white. And last year I did that strange orange variety. It sure did light up the place. Most of the tulips survived the voles – that trick with Bon Ami in the hole must have worked. It will be weeks before they bloom, though, and then the hostas will come along to cover their straggly ending. On the other hand, it is a place of sheer wonderment for those to whom spelling comes naturally. For the latter, they can only ponder (or gape at) the inventive phonetic solutions that poor spellers have come up with to address their deficit.

On the other hand, it is a place of sheer wonderment for those to whom spelling comes naturally. For the latter, they can only ponder (or gape at) the inventive phonetic solutions that poor spellers have come up with to address their deficit. Ever since I put her on clonazepam it has made all the difference. Ms. Congeniality? Not exactly. But she will come when called now instead of hiding under the bed, and sometimes, of her own volition, she will jump up where you’re sitting and peer into your eyes. Black cats seem to like eye contact.

Ever since I put her on clonazepam it has made all the difference. Ms. Congeniality? Not exactly. But she will come when called now instead of hiding under the bed, and sometimes, of her own volition, she will jump up where you’re sitting and peer into your eyes. Black cats seem to like eye contact.