Ted Cruz’s announcement of his preferred running mate has enhanced the nomination process by giving voters pertinent information. They already know the only important thing about Trump’s choice: His running mate will be unqualified for high office because he or she will think Trump is qualified.

- George Will

The Washington Post

Saturday, April 30, 2016

Mayday! Mayday!

One can see a significant change in the DC local homeless problem. It appears homeless people are now building encampments or becoming "human barnacles" attached to the outside of existing businesses. At night some of our streets can remind one of photographs once found in old issues of National Geographic Magazine. District of Calcutta? Today we are confronted with "pus poverty" an outcome of a sick society. Income equality is a clinical way of explaining greed. If we are not careful we will walk pass our fellow human beings no longer mobile with their pushcarts - instead they have arrived at their final destinations. They have stopped searching and seeking shelter, their worn clothes, torn by the smell of their street days are slowly becoming invisible to our eyes. We have returned to living behind veils as if a curtain just fell on life's stage. After gentrification comes a tale of two cities and the story of how we died not once but twice. We died in the arms of strangers, we died looking into mirrors, we died wishing there was a change in the weather. Summer is coming. I fear a dark, dank coldness, linked to our own climate change and indifference. I fear we have all become sufferers.

Thursday, April 28, 2016

Wednesday, April 27, 2016

THE ALDON NIELSEN PROJECT 2015

MAPPING THE OUTER LIMITS

E. Ethelbert Miller - The

Aldon Nielsen Project # 18

Q: In WHAT I SAY one finds the poets presented

in alphabetical order. I felt your book didn't explain what the various writers

had in common. Why didn't you arrange the book around issues of theme and

structure? I'm a substitute high school

or college teacher and the class is studying the poetry of Julie Ezelle Patton.

Where do I begin? If she defines herself

as a conceptual artist what boundaries is she crossing when it comes to poetry?

In the end, the decision to

arrange the contents of both What I Say

and Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone

alphabetically by poets’ last names was a choice rooted in a desire to leave

readers free to pursue their own mappings through the era (roughly 1948 to now)

that the two anthologies carved out. We could easily have gone many other

routes, and even toyed with the idea of a random positioning. (At least I toyed

with that idea; not sure today that I ever shared the thought with my

co-editor, Lauri Ramey.)

Some quick background: for many

years, readers of my book Black Chant

had been encouraging me to publish an anthology of the poetry that I had

discussed in that volume, a volume dedicated to exploring a territory within

African American poetry that had gotten somewhat sidelined in the decades after

the Black Arts Movement. One of the many striking things about the Black Power

and revolutionary years of, say, 1965-1975, was that so many writers, and

especially poets, had been at the forefront of the movements, But even in the

years leading up to the Black Arts period, many of the African American poetry

anthologies had been truly eclectic in scope, attempting to represent the broad

aesthetic range of Black verse in America. You can find prose poems in anthologies

as early as the 1920s, for instance. At the high water mark of 60s/70s

anthologizing, this phenomenon was if anything yet more pronounced. It was in

anthologies that I first read the works of such poets as Russell Atkins, Tom

Weatherly, Elouise Loftin, Jay Wright, June Jordan and so on and on. With the

waning of the Revolutionary 60s/70s, there was an observable decrease in the

mainstream publishing of Black poetry anthologies, though many smaller presses

kept up the pace. As the 80s came along, the strengthening multicultural reform

movements in universities again spurred commercial publishers’ interest in

supplying a growing market for classroom texts and the general market. But a

funny thing happened; many of the new anthologies struck me as being

considerably narrower in their aesthetic choices than had books I’d read in my

youth such as Baraka and Neal’s Black

Fire. Among the many things I set out to do in writing Black Chant was to historicize the intellectual fashions that had

led to the marginalization of poetry in general and more aesthetically radical

poetry in particular. Many among my small audience of readers wanted to have a

collection they could use in their own work and teaching that was more nearly

representative of African American poetry that was as radical in the writing

itself as it was in its thematics. (Think Baraka! Think Lorenzo Thomas.) So

there was no surprise in the urgings I was hearing towards an editorial

project.

But there were material

concerns. Chief among them was the fact that for so many of those years I was

teaching a 4/4 load and had no access to research funds or research assistants.

(There was also the fact I’d already observed that it was probably wiser to

wait till I was tenured to take on a time-consuming editing task that, for all

its obvious value to readers and to scholarship, would count for little in a

tenure case.)

These were among the factors I

was outlining to Lauri Ramey the day she first phoned me from Hampton

University to chat, and suggested the need for such an anthology. Her immediate

response was, “I’ll help you.”

So that’s how we got to the

project in the first place, a story I have been telling at panels and readings

in support of our second volume, What I

Say. We have been as clear as we could be throughout the project that we

are aware that others could easily chart a different course through the same

history. Some times this was not by our own choice. (It still pains me that

there is nothing from Jay Wright or Julia Fields in our first collection, but

they each, for different reasons, didn’t care to be anthologized further at the

moment. Similarly, I keep thinking that if I had delayed finalizing What I Say just a few months longer [it

had already been years, mostly due to my commuting life mode] we could have

included Tonya Foster, LaTasha Diggs and others.) Many will look at the word

“innovative” in our subtitles and immediately think of poets they would have

added under that rubric. If anything, my response is to hope that they will. We

need more such books. One place to look for an alternate reading of things is

the dossier of radical poets prepared for the journal boundary 2 by Dawn Lundy Martin just last year.

In the end, the alphabetical

organization was our way of encouraging readers to come to their own

conclusions about lineages and affiliations. This doesn’t always turn out as I

would have it. In our short preface to What

I Say we mention the fact that a few of the poets in that book had

friendships with various of the L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E poets. I’ve observed in the few

months since the book appeared that some people introducing our work at

conferences and readings have a tendency to highlight that fact, somewhat

obscuring our book’s evidence of the many routes that different poets took to

the experimental modes visible and audible in their works. In the many decades

since Grove Press published Donald Allen’s The

New American Poetry anthology, many critics have argued with the

implementation of his geographical groupings of the poets therein. One Amazon reviewer of Ron Silliman’s

collection In the American Tree

reacted to that book’s organization, writing “I think in my copy I crossed out

the words West and East in the book and wrote above them ‘Us’ and ‘Them.’” On

the other hand, chronological arrangements (most often organizing by the poets’

dates of birth) struck me as entirely too likely in this case to present a

false picture of a ceratin “progress.” Thematic arrangements can often be

productive, but generally this is true when the anthology itself is built

around a particular set of subject matters, rather than, as in our case, built

around the desire to assert an important continuing history of experiment. I

don’t know that I have seen many anthologies built around particular structures,

unless we’re thinking of things like sonnet collections, or haiku anthologies.

Part of the point of our books is to underscore the continuous generation of

new forms. And yes, as editors we could have produced a much longer explanatory

introduction, but I have an aversion to repeating arguments that I have made in

print already, an aversion that comes from having had so many editors over the

years encourage me to say again what I have already said, when what I want to

say is something else. (Those who have not yet seen What I Say can look forward to its wonderful introductory essay on

the subject of anthologizing by poet C.S. Giscombe.) And I know it’s something

of an evasion to advise people who want to know what all these poets have in

common to go read Black Chant and Integral Music, and the many essays I’ve

published since . . .

But here’s the nutshell, already

burst, the contents escaping in all directions.

The poets presented in these two

anthologies have in common their participation in the ongoing aesthetic rupture

that shows up in poetry with Modernism.

Now, experience teaches me that some will read that and rush to the same

sort of mistake as those who overemphasize the role of White experimentalists (or

even White mentalists) in these developments.

Here’s the thing, as we say

nowadays, relatable, in fact. I follow

C.L.R. James and W.E.B. DuBois in making the argument that the peoples of the

African diaspora were not just subjects of Modernism, not simply inspiration

for so many of Modernism’s breakthroughs, but were demonstrably producers of

Modernism, even, as DuBois and James teach us, the very condition of

possibility for the emergence of Modernity as a historical fact.

So, yes, we can read Amiri

Baraka telling us of his early readings in Joyce, Eliot, Beckett, cummings,

Yeats etc. But what sort of readers

would we be if we overlooked the equal importance in his evolution of Langston

Hughes, of James Weldon Johnson (author, in my view, of the first Modernist

novel by an African American author), and of all those preachers he heard in

his parents’ church? We’d be, sad to say, the kind of readers who have written

so many essays overlooking just that lineage.

What the poets in our

anthologies have in common, then, is Williams (William Carlos), Hughes, Olson,

Johnson, Moore, Césaire, Lorca, Senghor, and let’s not forget the poetics of

Armstrong, Ellington, Williams (Mary Lou), Monk, Coltrane, Ayler . . .

These poets are not the only

ones who have read, listened to and been influenced by this lineage, but for

these poets these predecessor artists are not just subject matter and

inspiration. Williams revised the adage

about art being nature’s mirror by urging us to see what the poet does as not

copying nature, but doing what nature does, bringing new things into being.

Césaire represented his people, but his poetry was no simple act of

representation.

Terms like “MFA” poetry are

clearly an unsatisfactory shorthand. We could substitute terms like “mainstream

poetry,” “AWP poetry,” “official verse culture.” Back at the time of Allen’s New American Poetry it was common to

divide the poets into the academic and its anti-, but those were terms

describing styles of writing, not the professional locus of the poets

themselves, or even their level of scholarly learning. Any of these terms must

be written under erasure. For example, both mainstream MFA programs around the

country and the AWP itself are clearly more welcoming of the more radical

poetries now than they were in earlier years. (For so much of the 80s and 90s,

the AWP newsletter seemed to be on a campaign against poststructuralism AND

cultural Studies AND surrealism and its rapidly proliferating offspring.) At

this past AWP conference in Los Angeles, there was a panel celebrating Rae Armantrout,

Harryette Mullen gave a reading, and there was even a What I Say panel. A few poet/editors have tried to float terms such

as “hybrid verse” or “post-avant” to signal this greater mainstream

receptiveness – But all you have to do is look at the way postmodern visual art

is now enshrined in major museums and then look to the rewards structure of the

American poetry community (the MacArthurs are a good place to see this) to

recognize that when it comes to America’s poetry culture, there is very much still

a mainstream, with its describable and preferred poetics.

And I think this is

demonstrated, too, by the fact that so many years had passed since we’d last

seen anthologies that did the work of these two books. Ken Burns did the neat

trick in his Jazz series of pairing

onscreen diminutions of the achievements of Ornette Coleman with a CD series

that sold Ornette Coleman. Similarly, while nobody, I trust, would think of

publishing something that announced itself as an encompassing anthology of

contemporary African American verse without including the work of Baraka, they

mostly don’t include Russell Atkins or Julie Patton.

As to teaching Patton, our

anthology is a good starting point, as you might not run into her work too many

other places. But even our book has its drawbacks. Patton’s long poetic tribute to Baraka should

have been in color. We simply had no money for publishing color plates. What we

did publish affords an opportunity for students to confront not only the oral

tradition in Black verse, but also the unpronounceable in Black verse. Beyond

giving students a reason to think carefully about the relationships between the

soundings of poetry and the visual forms in which it appears, Patton also calls

for us to rethink our understandings of performance. Mention “performance

poetry” in most contexts and everybody will think of slams and open mic nights.

But how often does a Julie Patton appear at an open mic among all the emoters

taking their cues from people who took their cues from Def Poetry Jam? What has

happened is that too many take nothing more than the attitude and delivery mode

from what they’ve seen of the Black Arts, and don’t go to school with the

revolution in verse that accompanied the political revolution. There will soon

be an example of Julie Patton in performance online, drawn from the publication

reading for What I Say that took

place at Cal State LA’s new downtown campus during AWP. The audience never

knows what Patton is going to do when she approaches a microphone, not even

audiences that have been to her gallery shows or have seen her with a band. On

the night of the reading in LA, she began by making a few opening comments;

next thing we knew she was singing a complex (unheard of?) improvisation that

made music from the names of other poets in the book, addressed individuals

sitting in the audience, even incorporated a bit of the epic piece by her

that’s in the anthology. Performances like that demand that we attend to this

as an art form that belongs in the ranks with our greatest page poets. Given

the long history we have with being able to speak intelligently about Sonia

Sanchez’s improvisations, Jayne Cortez’s superrealism, Ntozake Shange’s

choreo-poems, Sun Ra’s chants, can it really be that difficult to comprehend a

multimedia poet of the stature of Patton? At the same time, should not Patton’s

work cause some disturbance in the field of poetic conceptualism as it is

currently constituted? In the last year

there has been a raging controversy surrounding racism and the works of Kenneth

Goldsmith and Vanessa Place, leading lights in what is presently termed

conceptual poetry, and yet that terming has a bad case of presentism. The

debates have gone on as though no Black artists had ever been involved in

conceptualism – No Adrienne Piper, let along Mendi and Keith Obadike, and

certainly no Julie Patton. Patton’s work not only interrupts standard

conversations around the boundaries of verse, it reconceives the conceptual

itself.,

But the bottom line for What I Say is, as it was for Every Goodbye Ain’t Gone, found in the

work itself. It is often said that “experimental poetry” teaches you to read it

as you read. These two anthologies are open to myriad openings of pathways

through the territories, and each pathway reveals another turning in the

question of what these poets have in common, and what we have in common with

them, a certain way, as Giscombe has it, of complicating the yakety yak.

POETRY NEWS FROM TERI CROSS DAVIS

Teri Cross Davis

Poetry Coordinator

Folger Shakespeare Library

201 East Capitol Street, S.E.

Washington DC, 20003

(p)202.675.0374

(f)202.608.1719

O.B. Hardison Poetry Series 2015/16

Embrace the Night

Folger Poetry Board Reading

Sir Andrew Motion

Mon. May 9 7:30pm

Lineage: From the Black Arts Movement to Cave Canem

Mon. June 13 5:30pm- 9:30pm

5:30- 6:45pm Cave Canem Open Mic featuring fellows Robin Coste Lewis, Joel Dias-Porter, Kamilah Aisha Moon and more with Derrick Weston Brown, moderating.

7:30- 8:30pm Reading and discussion with Nikki Giovanni, Haki Madhubuti, and Sonia Sanchez, Kwame Alexander moderating.

8:30-9:30pm Cave Canem co-founder Toi Derricotte, Gregory Pardlo, Kyle Dargan, and Rachel Eliza Griffiths.

Tuesday, April 26, 2016

THE NBA OF LIFE

Curry and now Chris Paul injured during the NBA playoffs. Nothing should ever be taken for granted. Games like life are filled with disappointments and constant surprise. We wake to earthquakes.

Monday, April 25, 2016

I want to tell you everything I know about being alive but I

missed a lot of living that way -

missed a lot of living that way -

Marie Howe (The Kingdom of Ordinary Time)

Sunday, April 24, 2016

Martín Espada

Martín Espada

Listen to Audio Podcast (28:43 minutes)Martín Espada was born in Brooklyn in 1957. He has published almost twenty books as a poet, editor, essayist and translator. His new collection of poems is called Vivas to Those Who Have Failed (2016). Other books of poems include The Trouble Ball (2011), The Republic of Poetry (2006), and Alabanza (2003). His honors include the Shelley Memorial Award, the PEN/Revson Fellowship, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. The Republic of Poetry was a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize. His book of essays, Zapata’s Disciple (1998), was banned in Tucson as part of the Mexican-American Studies Program outlawed by the state of Arizona. A former tenant lawyer, Espada is a professor of English at the University of Massachusetts-Amherst.

Quote of the Day

Every historical inquiry has a saturation point, past which new inquiry becomes simply old inquiry repackaged...

- Adam Gopink, The New Yorker, April 25, 2016

- Adam Gopink, The New Yorker, April 25, 2016

Friday, April 22, 2016

Well, I'm back from New York. On Wednesday I gave a reading at The New School. On the program were Jarita Davis and Camille Rankine. The event was sponsored by Cave Canem. I thought it went well. A number of old friends in the audience.

Grace was kind enough to rent a car and take me to Yonkers to see my sister. Sad to see her condition. We lose our minds so quickly. I need to write about this before my own mind falls apart. I see it coming. Time to prepare for the end.

Grace was kind enough to rent a car and take me to Yonkers to see my sister. Sad to see her condition. We lose our minds so quickly. I need to write about this before my own mind falls apart. I see it coming. Time to prepare for the end.

Saturday, April 16, 2016

NEW YORK, NEW YORK...Bert back in the City.

April 20, 6:30 pm

New Works Reading: Jarita Davis, Camille Rankine and E. Ethelbert Miller

Join us for an exciting evening of poetry with fellow Jarita Davis and Cave Canem friends Camille Rankine and E. Ethelbert Miller. Davis is a former Writer-in-Residence at the Nantucket Historical Association and author of Return Flights (Tagus, March 2016). Rankine’s debut full-length collection is Incorrect Merciful Impulses (Copper Canyon, 2016), described by Stephen Burt as “sensuously

Join us for an exciting evening of poetry with fellow Jarita Davis and Cave Canem friends Camille Rankine and E. Ethelbert Miller. Davis is a former Writer-in-Residence at the Nantucket Historical Association and author of Return Flights (Tagus, March 2016). Rankine’s debut full-length collection is Incorrect Merciful Impulses (Copper Canyon, 2016), described by Stephen Burt as “sensuously  immediate . . . and trailing—with fearful eagerness—the spirit of Plath.” Miller is the author or editor of many books, including the memoirs The 5th Inning and Fathering Words: The Making of an African American Writer. The Collected Poems of E. Ethelbert Miller is forthcoming from Willow Books in spring 2016. Free and open to the public. Book signing to follow.

immediate . . . and trailing—with fearful eagerness—the spirit of Plath.” Miller is the author or editor of many books, including the memoirs The 5th Inning and Fathering Words: The Making of an African American Writer. The Collected Poems of E. Ethelbert Miller is forthcoming from Willow Books in spring 2016. Free and open to the public. Book signing to follow.

The New School

Wollman Hall, Eugene Lang College

65 West 11th Street

Room B500

New York, NY 10003

April 20, 6:30 pm

New Works Reading: Jarita Davis, Camille Rankine and E. Ethelbert Miller

Join us for an exciting evening of poetry with fellow Jarita Davis and Cave Canem friends Camille Rankine and E. Ethelbert Miller. Davis is a former Writer-in-Residence at the Nantucket Historical Association and author of Return Flights (Tagus, March 2016). Rankine’s debut full-length collection is Incorrect Merciful Impulses (Copper Canyon, 2016), described by Stephen Burt as “sensuously

Join us for an exciting evening of poetry with fellow Jarita Davis and Cave Canem friends Camille Rankine and E. Ethelbert Miller. Davis is a former Writer-in-Residence at the Nantucket Historical Association and author of Return Flights (Tagus, March 2016). Rankine’s debut full-length collection is Incorrect Merciful Impulses (Copper Canyon, 2016), described by Stephen Burt as “sensuously  immediate . . . and trailing—with fearful eagerness—the spirit of Plath.” Miller is the author or editor of many books, including the memoirs The 5th Inning and Fathering Words: The Making of an African American Writer. The Collected Poems of E. Ethelbert Miller is forthcoming from Willow Books in spring 2016. Free and open to the public. Book signing to follow.

immediate . . . and trailing—with fearful eagerness—the spirit of Plath.” Miller is the author or editor of many books, including the memoirs The 5th Inning and Fathering Words: The Making of an African American Writer. The Collected Poems of E. Ethelbert Miller is forthcoming from Willow Books in spring 2016. Free and open to the public. Book signing to follow.

The New School

Wollman Hall, Eugene Lang College

65 West 11th Street

Room B500

New York, NY 10003

Tuesday, April 12, 2016

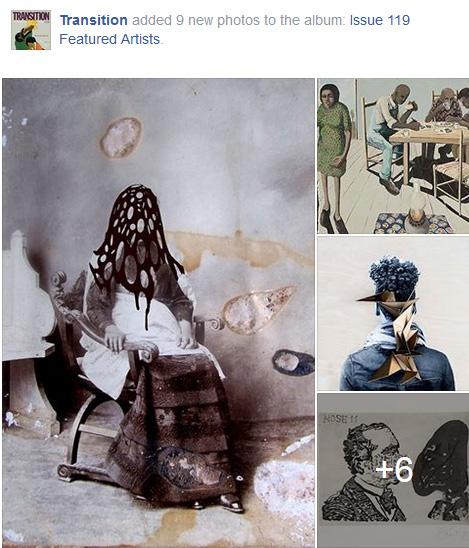

The Magazine of Africa and the Diaspora, est. 1961

|

Issue 119 - Afro-Asian Worlds

|

The issue also highlights activism in its various forms, featuring insights from multiple generations of civil rights leaders in St. Louis, Missouri, including Percy Green, Tef Poe, and Jamala Rogers; startling statistics about the history of solitary confinement in the U.S. prison system in an essay by Adam Ewing; and Francis Nenik's portrait of undersung South African poet and activist, Edward Vincent Swart. In addition to powerful poetry and fiction by Bryan Washington and Desiree Bailey, Issue 119 revives Transition's infamous Letters section, giving our readers a forum for voicing opinions and responses. Read the issue on JSTOR, Project Muse, or order from IUP!

119 Featured Article

Generations of Struggle

Activists and scholars Percy Green II, Robin D. G. Kelley, Tef Poe, George Lipsitz, and Jamala Rogers with Elizabeth Hinton discuss more than five decades of black action in St. Louis, from the Civil Rights Movement to Black Lives Matter.

"If you're going to come into one of these communities where there's black folks, and you're going to pull your gun out and shoot, you will be met with resistance. We're going to curse at you. We're going to throw some stuff at you. We might even tip over a police car or two, depending on how we feel that day. But you will not just come into our communities and gun people down and be met with nothing." - Tef Poe

Read Generations of Struggle (a full transcript of this conversation will appear in Kalfou later this spring).

|

|

HEY JOE!

Dear All:

I hope this email finds you all well.

If you haven't RSVP'd yet, this is a reminder that you are all invited to our Member's-Only Reception this Thursday, April 14, from 5:30-7:30 PM, at The Writer's Center, prior to Ethelbert's 40th Anniversary Reading.

Stay for his reading at 7:30 PM, which will feature a moderated conversation with News4 anchor Wendy Rieger, who is an enthusiastic fan of Ethelbert's work.

Contact genevieve.deleon@writer.org with any questions or concerns you may have. We look forward to seeing you!

Sincerely,

Joe

Joe Callahan, CFRE

Executive Director

The Writer's Center

4508 Walsh Street Bethesda, MD 20815t: 301.654.8664 x203 f: 240.223.0458

e: joe.callahan@writer.org w: Writer.org

Executive Director

The Writer's Center

4508 Walsh Street Bethesda, MD 20815t: 301.654.8664 x203 f: 240.223.0458

e: joe.callahan@writer.org w: Writer.org

Monday, April 11, 2016

It was June (Jordan) who introduced me to the music of Gato Barbieri. How often did I listen to his album - Caliente? Music is what we need to keep the memories warm. Barbieri died a few days ago.

Sunday, April 10, 2016

It's difficult to read or listen to current social and political commentary. We keep going in the same circles. Where are the prophets for a new day? Look for two-sided dumbness to emerge at both the Republican and Democratic conventions this year. Some young people will arm themselves with rhetorical muskets. Look to the Left or Right Wing and one sees a plane descending. Pilot, Pilot, help us restore the civility we've seen to have lost. After Obama one can only pray for a Larry Doby.

Time to get back to writing E-Notes and not simply posting information. Too many things happening in my life right now but no excuses.

Trying to help my sister keep the darkness away. Helpless in DC.

Pushing myself to do more - clock ticking.

How many years left?

I'm happy The Collected Poems...is out there. The book will either be praised or ignored.

I'm not expecting too much.

2016 continues to be a year of transition and transformation; as well as a rite of passage.

Trying to help my sister keep the darkness away. Helpless in DC.

Pushing myself to do more - clock ticking.

How many years left?

I'm happy The Collected Poems...is out there. The book will either be praised or ignored.

I'm not expecting too much.

2016 continues to be a year of transition and transformation; as well as a rite of passage.

Friday, April 08, 2016

View it in your browser.

| |||||||||||||||

|

| In partnership with the Library of Congress,

Poet Lore presents

An Evening of Uruguayan Poetry

with Jesse Lee Kercheval

Thursday, May 12

6:30 PM

at

Montpelier Room, James Madison Building

Library of Congressin Washington, DC

Poet and translator Jesse Lee Kercheval will read fromthe selections of Idea Vilariño's poetry featured in Poet Lore's Spring/Summer 2016 issue as well as translations of several noteworthy Uruguayan female poets.

RSVP on Facebook (optional)

|

Jenny McKean Moore Series: A Reading by Claudia Rankine

Join us for the next installment of The Jenny McKean Moore Reading Series featuring Claudia Rankine, who will read from new book Citizen: An American Lyric. Her new work won both the PEN Open Book Award and the National Book Critics Circle Award for poetry, as well as being a finalist for the National Book Award.

Rankine is the recipient of the Poets and Writers Jackson Poetry Prize and fellowships from the Lannan Foundation and the National Endowment of the Arts. A poet, essayist, playwright, and editor, she is the Chancellor of American Poets and the Aerol Arnold Chair in the University of Southern California English Department. Rankine has published five collections of poetry, including Don't Let Me Be Lonely, Si Toi Aussi Tu M'abandonnes, The End of the Alphabet, Plot, and Nothing In Nature Is Private. Her two plays are entitled Provenance of Beauty and Existing Conditions.

Greywolf Press describes Citizen as follows:

Rankine is the recipient of the Poets and Writers Jackson Poetry Prize and fellowships from the Lannan Foundation and the National Endowment of the Arts. A poet, essayist, playwright, and editor, she is the Chancellor of American Poets and the Aerol Arnold Chair in the University of Southern California English Department. Rankine has published five collections of poetry, including Don't Let Me Be Lonely, Si Toi Aussi Tu M'abandonnes, The End of the Alphabet, Plot, and Nothing In Nature Is Private. Her two plays are entitled Provenance of Beauty and Existing Conditions.

Greywolf Press describes Citizen as follows:

Claudia Rankine’s bold new book recounts mounting racial aggressions in ongoing encounters in twenty-first-century daily life and in the media. Some of these encounters are slights, seemingly slips of the tongue, and some are intentional offensives in the classroom, at the supermarket, at home, on the tennis court with Serena Williams and the soccer field with Zinedine Zidane, online, on TV—everywhere, all the time. The accumulative stresses come to bear on a person’s ability to speak, perform, and stay alive. Our addressability is tied to the state of our belonging, Rankine argues, as are our assumptions and expectations of citizenship. In essay, image, and poetry, Citizen is a powerful testament to the individual and collective effects of racism in our contemporary, often named “post-race” society.

Event Date and Time:

Monday, April 11, 2016 - 7:30pm

Event Location:

Gelman Library, Room 702

Wednesday, April 06, 2016

Application Open for June Master Class

Monday, June 13, 9:00 AM–5:00 PMFROM THE BLACK ARTS MOVEMENT TO CAVE CANEM

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of the Black Arts Movement and the 20th anniversary of Cave Canem, a day-long symposium featuring two panels and a master class in children’s literature. Evening readings to follow at the Folger Shakespeare Theater. This event is co-sponsored by the Library of Congress Kluge Center, the Folger Shakespeare Theater, PEN/Faulkner Foundation, and Cave Canem Foundation.

Location: LJ-119, First floor, Thomas Jefferson Building

Contact: (202) 707-5394

Application open now. Click here to apply.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Excerpts from the 2016 PEN Open Book Award Shortlist

Excerpts from the 2016 PEN Open Book Award Shortlist