Is it

possible to fall in love with a film on the basis of a few scenes? Can a few 'stills' be so

chiseled, so jewel-like that the failings of Life can be overlooked?

This is not a commentary on post-war Japan and its interminably complicated bureaucracy. The main purpose of the film is certainly not to convey the horrors of a world that is over-run by functionaries and the impersonal. Perhaps only a modern European imagination could really talk seriously about organization and a really old one (Greek) about Labyrinths. No, the portrait of the obfuscations and willed deafness are light and almost comical-perhaps even superficial- to our eyes.

The film's central

preoccupation is elsewhere. But how to make a film about life, the living...except by talking about death. There is no heroic striving for immortality

against this inevitability but nor is there a passive acceptance of Necessity. Death is, and can only be, something that is ambiguous:

Thanatos and

Eros.

The film starts off with a depiction of a life that is not lived but simply passed.

(Back in my school days there were the following categories: distinction, merit, pass, good fail, and fail). Everyone goes through the motions and this is what qualifies as doing just enough. A good fail. The whole aim of such a life is to avoid life, to look busy and run down time. What would we do without our clocks and watches! To do nothing 'is' to be nothing. Already, one wonders how deep rooted these ideas -of death and nothingness-are in the Japanese spirit.

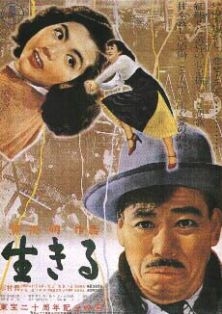

The main protagonist of the film devotes himself to his work (which is really making sure that no work gets done). A singular dedication to an ideal, replete with the bourgeois markers of respectability: a hat, a certificate in honour of all those of years of service, are what bind a life and its serial

moments together. Otherwise, as

Watana-be says in a moment of reflection,

I can't remember a single day . After the death of his wife he decides to live a solitary life-ostensibly for the sake of his child , but in reality we learn that this too is a farce, an excuse. For how long can we blame external

circumstances for our choices? When all is said and done we

are what we choose to be. He is given the nickname of 'the mummy' and this is highly appropriate for one of the world's living dead, for someone who has tried to freeze time.

To escape from the inevitable by creating a routine for oneself. Perhaps the whole of human culture is nothing more than this. Work, too, is one such social construction, as are our intellectual endeavours. As long as one is active one is alive. But in work the aim is not just to feed the stomach. Man shall not live by bread alone. Gradually, he realises that he is being eaten up from within. He has a disease that everyone knows of, but which no-one has to courage to name...

The first sparkling moment comes when he is torn between telling his son about his stomach cancer and patiently

keeping it to himself, as he has with

everything else. Then in a moment of utter decisiveness (or is it desperation) he rushes up the near vertical flight of stairs, clambering on his hands and feet. But in the dark he comes to an abrupt stop. How to speak the unspeakable? Can the father ever initiate the son into the inevitable? Would it help either of them? If one has to stop to think about an emotion was it a true one in the first place? As he halts the light dramatically fades away and he is rooted to the spot, half way between different worlds, as it were, hesitant and unsure of himself. Can one unwrap the cloth that has bound a soul for so long and then expect love to still flourish? In that moment-which lasts for an eternity- he is made acutely aware of the infinite distance between himself and his own

flesh and blood. It is not death but life itself that alienates us from the life of others.

He thinks back to those early years with his son. Has his life with him been anything but a catalogue of

unforeseen and unpredictable departures (the death of his wife, the son going off to war, him having to miss his son's operation)? Is life itself anything but a series of departures ? Even the only moment he can remember with any pride soon turns into a reflection on his helplessness before the

uncertainties that his son faces. He can, like a mummy, provide

security but not love. Later, when he recalls the distance between

himself and his son, he says it is like drowning, sinking in sheer darkness, reaching out to cling on to something. We

fall into love and we

fall out of it.

The next magical scene occurs when he is told by a co-worker over lunch that despite all of his denials he still loves his son. This is, perhaps, the most amazing shot in the whole film. He looks up, shyly, almost embarrassed, and then his face radiates with a smile as he comes to recognize the truth of this. It comes to him like a revelation, a light shone on the dark corner of his musty soul moves to the surface, illuminating the old man's face. This is the beginning of his redemption. The earlier attempt-which had seen him abandoning himself to a night of pure pleasure-was utterly futile and he had known it to be so as well. For what value can there be in fleeting sensations that live for a day then die? He may change his hat, temporarily adopt a new personality, but none of this will do: The reality of poetry is nothing if not lived. One can never drown out the pain and a life without thinking about, working for, others eventually ends up in the intoxication of the self. Melancholy, Kirk

Douglas once said, is another name for egotism.

The solution-if it is as solution-comes to him at a restaurant where someone

else's birthday is

begin celebrated. And we are not surprised by this for we are really witnessing a new birth.

There are other stylistically interesting features-like the way in which the siren goes off at precisely the last time that we see

Watana alive. Perhaps the most memorable scene , though, is when after a few frenetic songs have been played and danced to in a

night cub Watana starts to sing an old song from the 1910's. Everyone stops what they are doing, at once

fascinated and repelled by his hauntingly tragic voice that seems to be coming to them from elsewhere. They are transfixed by his unearthly voice but the song

itself is really about the earth and life. A few people move away from him, unable to bear the telling of it. There are some truths that not even song can carry.

It is as if Death

himself is singing but a death that is tired of dying and that wants to remind people of life. Up to that moment the people in the nightclub had been dancing crazily to a music that was not their own. When the real beauty of life is in accepting its transience and being finely aware of it, not an overcoming of it or a forgetting of it. But

Watana also knows that the bitter-sweetness of life is that life is blind to its own end, that only death can remember what life really is....